EdBuild: How a New Player in the Ed Reform Game Is Skipping the Usual Battle Lines to Focus on Funding

What she means is that EdBuild doesn’t fall squarely on either side of the traditional battle lines that seem so clearly drawn in the education debate. That might be surprising considering Sibilia’s background and EdBuild’s funders.

Sibilia’s last job was as vice president of fiscal strategy at StudentsFirst, the arch-reform organization founded by former Washington, D.C. schools superintendent Michelle Rhee. And EdBuild’s funders include reform-driven philanthropic organizations such as the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, The Peter and Carmen Lucia Buck Foundation, and the Walton Family Foundation.

EdBuild’s distance from the rest of the education world is both literal and figurative. Its office sits in a large art deco building in Jersey City, New Jersey, far from the policy fights that take place mostly in big cities and state capitals.

But what really sets EdBuild apart from the reform community is its focus. Instead of emphasizing the two traditional reform pillars — school choice and teacher quality — Sibilia’s organization is trying to change the conversation to focus more on funding and equity.

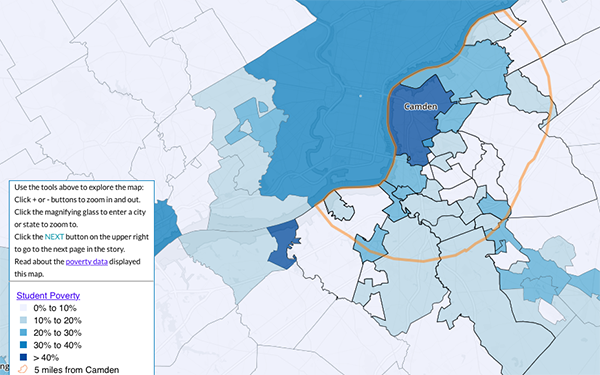

In that vein, EdBuild created a map, showing economic segregation and school resource inequality, which Sibilia previously wrote about in The Seventy Four.

EdBuild highlights the hardship of places like Camden, New Jersey, which has one of the poorest school districts in the country. The city’s public schools, within striking distance of Philadelphia’s suburbs, are surrounded by much wealthier districts, leaving “the children of Camden … fenced off from their more affluent peers — in effect, sacrificed to keep the poverty of the city from dragging down the property wealth of its neighbors.”

“We’re talking about things that the typical reform community is not talking about and hasn’t been talking about,” Sibilia says.

In starting EdBuild, Sibilia has waded into a long-running question in the education world: whether giving schools more money is likely to improve student outcomes.

The contemporary debate has its origins in an influential 1966 report called the “Equality of Educational Opportunity,” often referred to as the Coleman Report, after its lead author, sociologist James Coleman. It stated that a student’s family background had a significant effect on achievement, and while improved teacher quality and desegregation efforts could make an impact, Coleman found no clear relationship between school funding and student outcomes.

Later studies would find that the Coleman Report had understated the importance of school quality in student achievement.

But the idea that money and achievement were not related received significant attention and appeared to be corroborated by economist Eric Hanushek who echoed Coleman’s findings in a series of hotly debated studies. He wrote in one 2003 report that “a wide range of analyses indicate that overall resource policies have not led to discernible improvements in student performance.”

Hanushek’s work has been fiercely contested but his thesis seemed to take hold among many policymakers and politicians.

Hanushek advocated for more fundamental changes: expansion of school choice, test-based school accountability, dismissal of ineffective teachers, and bonuses for effective ones. Most of the reform community has focused on these policies — not funding.

Sibilia thinks this is a mistake. “Our friends on the reform side have done a disservice to this issue,” she says, pointing out that many skeptics of adding more money to the system focus on total funding, not how it’s distributed.

“It’s not about how much we’re spending but who we’re getting that money to,” Sibilia says. “When 23 states are still funding schools regressively — where low-income communities are getting less money than high-income communities — there is a problem with the level of effort we are putting forward as a country.”

Recent research gives credence to this view, including one blockbuster study, which found significant returns from court-ordered school funding infusions between 1955 and 1985. The researchers showed that “for low-income students a 10 percent increase in per-pupil spending each year for all 12 years of public school is associated with 0.43 additional years of completed education, 9.5 percent higher earnings, and a 6.8 percentage-point reduction in the annual incidence of adult poverty.”

Kirabo Jackson, a Northwestern University economist and lead author of the study along with Berkeley professor Rucker Johnson, told The Seventy Four, “The accepted wisdom among a large portion of researchers has been that the amount of financial resources provided to a school district or a school is unrelated to student outcomes."

The problem, he explained, is that the old research generally relied on crude correlations between spending and achievement, which might reflect that areas with higher poverty sometimes receive higher funding. His technique attempted to isolate the impacts of funding increases by comparing similar groups of students in the same district — one group whose education was better funded because of a court order.

“We have better data and we have improved methods," he said of his study, published in the peer-reviewed Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Jackson’s study is not without criticism, and he and coauthors in July 2015 engaged in a lengthy debate with Hanushek. But the weight of the research seems to be moving in Jackson’s direction. One study found that in Michigan additional funding led to increased college attendance and degrees among students whose schools were the beneficiaries. And two recent working papers from Stanford and Berkeley show gains in achievement and high school graduation from increases in spending.

Still others say the research has been settled for some time. A recent review of the research by Rutgers professor Bruce Baker concludes, “In short, money matters, resources that cost money matter, and more equitable distribution of school funding can improve outcomes.”

“We have pretty sound evidence on a number of things: substantive and sustained school finance reforms matter [and] targeting money to children who have greater need can help improve their short- and long-run outcomes,” Baker told The Seventy Four.

To Baker whether money is spent wisely is important, but “you can’t say [that] how you use [money] matters more than whether you have it, because if you don’t have it, you can’t use it.”

Hanushek isn’t buying it. He pointed to his previous research and reiterated his view that “you shouldn't expect consistent improvements in performance if you just add money.” He said “of course” money can matter, but “the problem in many schools is that there aren't very strong incentives to use extra funds to improve student performance."

EdBuild’s mission is seemingly simple: “to bring more common sense and fairness to the way we fund schools.” Sibilia says that objective has already evolved, focusing on the state — rather than the local — level.

That’s because, as Sibilia describes it, state funding is a mess. According to her, there are three major problems that plague many states:

-

Arbitrary funding, because many states haven’t followed — or don’t have — funding formulas, which sometimes leads to students with the same needs getting totally different levels of financial support.

-

Some states still fund schools based on classes, administrator salaries and other "system inputs," rather than the needs of students. This funding approach discourages innovation in the way education is delivered, forcing schools to continue to operate in a 1980s model in order to maximize funding from the state.

-

An overreliance on property taxes and oftentimes arbitrary district boundaries that lead to segregation and underfunding for the kids who need the money most.

EdBuild’s solution is a “weighted student formula,” which means money follows the child and is weighted based on need, so that more funds are attached to students in poverty or those with disabilities. This method, Sibilia says, “make[s] funding structures smarter, easier and less arbitrary, and allow[s] for the kind of flexibility that we would like to see for all schools.”

Baker, the Rutgers professor, says there are benefits to this approach, but cautions that the real issue is getting a progressive system — one that drives funding to high-needs students — through the political process.

“Weighted student funding is no panacea for making sure money gets to those who need it, because the weights are all subject to political deliberation,” he said.

An emphasis on providing additional funding based on need seems particularly important, given the goal among policymakers of ensuring that all students have access to quality teachers. Research suggests that high-poverty districts can use salary incentives to attract and retain teachers — but only if they have enough money to pay them.

Sibilia’s hope is to create proof points of success, where funding systems are reformed and outcomes are improved. The “end game,” she says, “is to prove that this kind of change is both politically feasible and makes for good policy in three or four states and encourage government adoption.”

EdBuild plans to do this by working directly with states to improve funding mechanisms, and publicizing these issues, including its maps highlighting inequity across the country.

In other words, Sibilia has a clear message to reformers and policymakers: Funding — how much and how it’s distributed — matters.

The question now is whether they will listen.

(Disclosure: The Seventy Four is also funded by the Walton and the Buck foundations. In 2012, I was an intern at StudentsFirst at the same time that Sibilia was there, though I never worked with her directly.)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)