New Employment Data: 5 Things to Know About the State of the Education Workforce

Aldeman: New federal data shows fewer people work in schools, but job openings are filled quickly and most positions lost were part-time.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

There are fewer people working in public education than there were in February 2020, before the pandemic hit.

Employee turnover rates remain high this year, but schools are more than replacing the people who leave.

In fact, all the job losses have come from part-time workers. And, once you factor in the number of hours those employees work, schools actually had slightly more staff than they did pre-pandemic.

These are just some of the findings from the latest national data. Here are five key takeaways:

1. The number of people working in education is still down

The chart below uses the latest Bureau of Labor Statistics jobs data through June 2023. Employment fell immediately as COVID-19 hit, and private-sector employers cut 16% of their workforce in the span of two months. But they have more than bounced back (the gray dotted line).

Public education’s job losses never got as bad as those in the private sector, but they’ve been slower to recover. At their worst, public K-12 and public higher education were both down about 9% (245,000 and 730,000 employees, respectively). As of the June data, public K-12 is still down 1.2% from its pre-COVID peak, whereas higher ed is still down 2.7%.

In contrast, private day care providers had a much steeper fall (down 36% in just those first two months) but have made a steady comeback. As of June, private day cares had 49,000 fewer workers than they did pre-pandemic (down 4.6%).

Note that these numbers represent individual people: a part-time worker and a full-time one are counted the same, no matter how many hours they work.

2. The recovery in K-12 looks a lot like the rest of local government

As shown above, the private sector looks different than the public sector. But within state and local governments, the pandemic recovery appears very similar. The graph below uses the same data as before, but this time it compares public K-12 employment against all other local government jobs (think police and fire departments, parks, libraries, etc.).

Education had a rockier recovery path in 2020 and 2021, but the different local government sectors have been on a remarkably similar trajectory throughout 2022 and so far in 2023.

3. Public K-12 and higher ed are both growing

The public education sector is expanding, and has been throughout 2021, 2022 and now 2023. It’s a simple function of how many employees leave (which the bureau calls “separations”) versus how many people are hired. The chart below compares these trends across all facets of public education. Unfortunately, K-12 and higher education are lumped together here, but as a reference point, K-12 represents about three-fourths of the total.

The data for 2023 are projections based on the data through May, but it provides some good news. Whereas employee turnover in education hit modern highs in 2022, it looks a bit lower so far this year. Meanwhile, public education hires are tracking slightly higher than for 2022, which was already one of the biggest years on record.

4. Education has a lot more job openings than normal, but it’s filling those openings at decent rates

There’s been a ton of interest in labor shortages within education, but how does it compare to other sectors? For starters, public education has the lowest job opening rate of any major industry tracked by the bureau. As of the latest data, there were 3.2 job openings for every 100 public education employees. That’s a rate of 3.2%. For comparison, the federal government rate was 5.6%, the private sector as a whole was at 6.1%, and other state and local governments were at 6.2%.

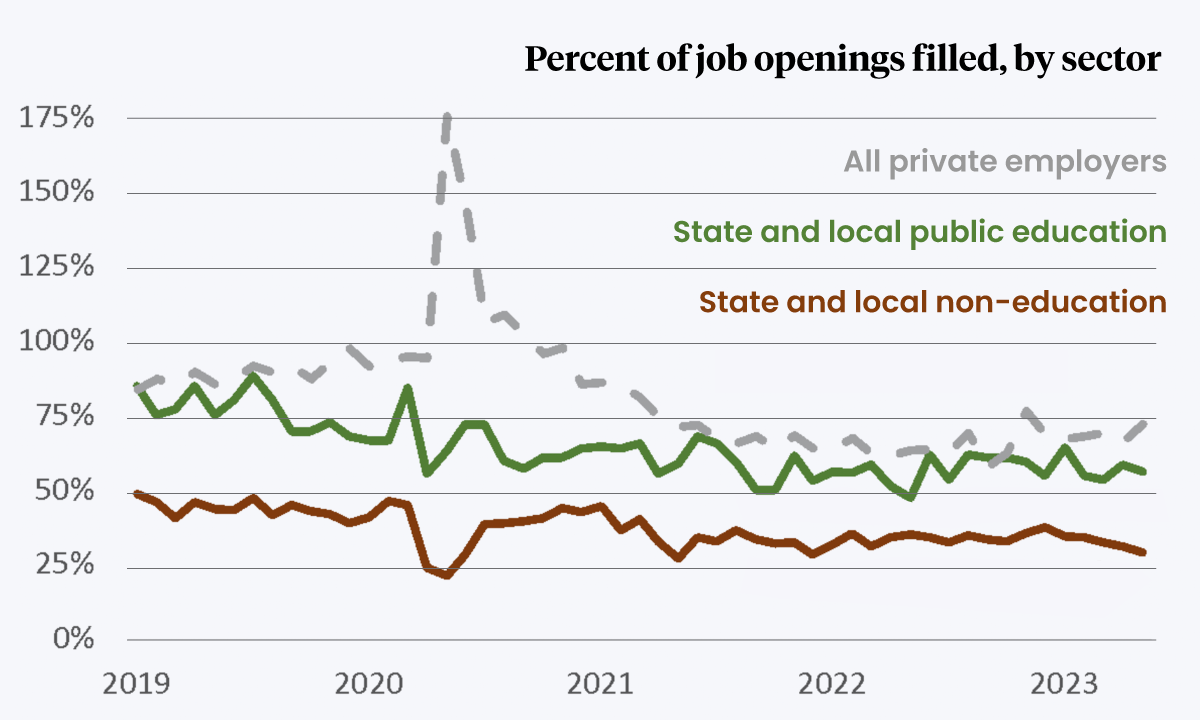

So how is education doing at filling its openings? Not terribly. The graph below shows an estimated fill rate by sector, which is the number of job openings divided by the number of new hires that month.

These have declined over time, save for a brief surge in summer 2020 when private-sector employers were rehiring workers without posting official job openings. It may not give much comfort, but public education employers (in green) are having an easier time filling their job openings than other state and local government agencies are in filling theirs.

5. The job losses were all among part-time workers, and total staffing has fully recovered

The data presented so far looks at individual employees, and when readers think of a typical education employee, they might naturally picture a teacher. But full-time classroom teachers represent only about 40% of the total K-12 workforce.

As I found earlier this year, public schools actually employ more teachers than they did pre-pandemic. They also had more school psychologists, district administrators, student support staff and guidance counselors.

So which jobs were lost? Mostly paraprofessionals and support staffers, including janitors, bus drivers and food service workers.

The latest Census Bureau data provides another way to slice it. It shows that public schools employed more full-time instructional and non-instructional staff in March 2022 than they did at the same point in 2019. What changed was a major decline in part-time workers.

This is why it’s important to look at total staffing rather than counting individual employees. Schools cut back on the number of part-time workers and the number of hours those employees worked. But total staffing levels (in full-time equivalents) are now above where they were coming into the pandemic.

Given that these data end in March 2022, and employment numbers are showing continued growth since then, it’s quite likely that staffing levels are even higher by now. And, because student enrollment remains depressed, that means student-to-staff ratios continue to fall.

We’ll have to wait for state and local data for finer-grained data on turnover rates and employment numbers by role. But for now, it’s safe to say that school staffing weathered the COVID dip and is now back above pre-pandemic levels.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)