New Civil Rights Data Shows Increase in Reports of Sexual Violence at School

Incidents of sexual violence in public schools increased by more than half between the 2015-16 and 2017-18 school years — from 9,649 to 14,938, according to civil rights data released Thursday by the U.S. Department of Education. And cases of rape or attempted rape doubled, the data shows, from 394 to 786.

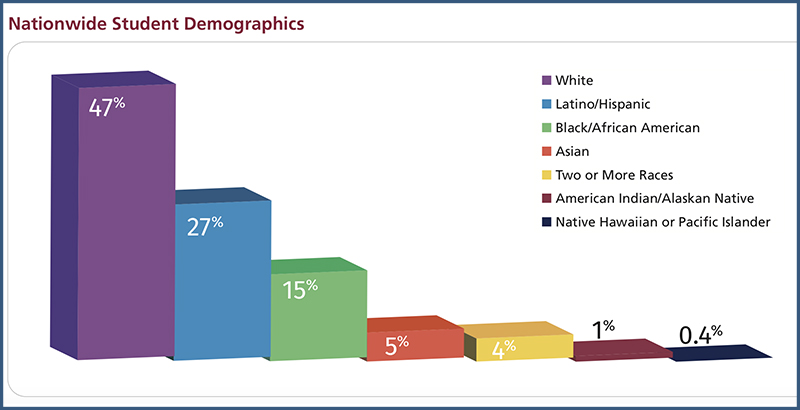

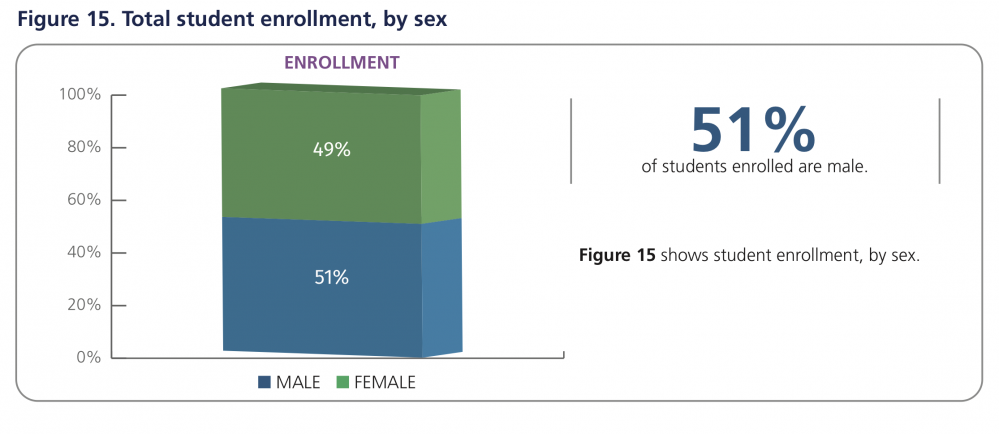

The increases were included in a brief the department released along with other civil rights data from more than 97,000 schools, representing almost 51 million students — a massive report, conducted every two years, that includes information on student enrollment and educational programs, separated by race and sex, and including English learners and students with disabilities.

The release of the Civil Rights Data Collection— used to monitor disparities and access to courses and other services — was held up by the coronavirus. In addition, the delayed 2019-20 collection will be conducted during the current school year. The department also announced last year that it was working to improve the quality of the 2017-18 data.

The brief on sexual violence and assault was used to highlight the department’s new Title IX rule that went into effect in August and requires schools to make significant changes in how they investigate and address sexual harassment and violence.

“No parent should have to think twice about their child’s safety while on school grounds,” Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos said in the report. “That’s why I’ve directed our [Office for Civil Rights] team to tackle the tragic rise of sexual misconduct complaints in our nation’s K-12 campuses head on.”

In 50 school districts, the civil rights office conducted more in-depth reviews when it found data that appeared out of the normal range. The agency, the brief said, is also conducting compliance reviews to investigate how cases are handled.

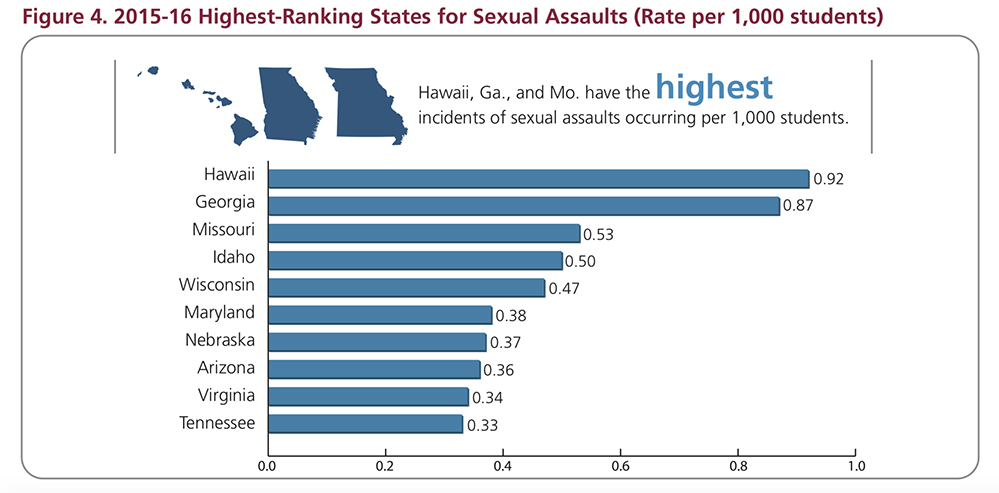

Some civil rights attorneys, however, wonder if the data review process has really improved. Some questioned, for example, the accuracy of state breakdowns of sexual assault data.

“Does anyone really think that there were zero incidents of rape or attempted rape in every school in 11 states? Or that Maryland schools experience 70 time more rapes and attempted rapes per student than New Jersey?” asked Seth Galanter, senior director of the National Center for Youth Law. “When the Department says that it devoted its resources to improving the quality of the data … and highlights data around sexual violence in one of only two issue briefs it released, then it needs to explain why it believes these results comport with reality.”

Four lawsuits have been filed against the department and DeVos over the new rule, including one with 17 states and the District of Columbia as plaintiffs. While the department said the rule makes it easier for students to report incidents, critics argue it removes protections for victims while seeking to make investigations more fair for the accused.

“If the rule is permitted to take effect, students across the country will return to school in the fall with less protection from sexual harassment,” the states’ lawsuit said.

The use of seclusion and restraint

The new civil rights report also includes a brief on the department’s efforts to address the use of restraint and seclusion in schools. The data shows that 101,990 students were restrained, either physically or mechanically in schools during the 2017-18 school year, with the majority of them having disabilities. In 2015-16, students with special needs made up 71 percent of those restrained and 66 percent of those placed in seclusion. In 2017-18, the rates increased to 78 percent of those restrained and 77 percent in seclusion.

Students with disabilities that were physically restrained were twice as likely to be white than Black — 52 percent compared to 26 percent. But the breakdown of students restrained with tape, rope, straps, weights or other devices was more even. Thirty-three percent of the students were white, 34 percent were Black, and 28 percent were Hispanic.

Seclusion was also more frequently used with white students than Black students — 60 percent compared to 22 percent.

“Given that approximately 13 percent of students in the U.S.have a disability, these statistics are alarming,” Lauren Morando Rhim, executive director of the National Center for Special Education in Charter Schools, said in a statement. “In the context of COVID-19, which has had an inordinate impact on students with disabilities, it is even more important to act to reverse disciplinary practices that perpetuate educational inequity.”

The report in recent years has alerted officials and advocates to significant racial disparities in discipline and has sparked the growth of alternatives to suspension.

The release of the 2017-18 data also comes just days after the Civil Rights Project at UCLA released an analysis of the 2015-16 collection, showing that middle and high school students lose more than a year of instruction due to suspensions in 28 districts, and that while racial gaps in discipline have narrowed some over time, Black students at the secondary level still miss 103 days per 100 students, compared to 21 days for white students.

Proposed changes not yet approved

Last year, the department proposed changes to the data collection, including adding allegations of sexual violence against school staff members at school as one of the new questions. Some argue that the question would miss incidents involving staff members and students. For example, the department’s agreement last year with the Chicago Public Schools over how that district handled complaints included a case of teacher-on-student sexual violence that occurred outside of school.

Other changes include collecting more information on religious-related bullying. But the department also plans to drop several questions related to young children, such as the race of preschoolers receiving out-of-school suspensions. The number of preschoolers suspended once would also be combined with the number receiving multiple suspensions.

Districts would no longer have to report whether their kindergarten programs are full day or whether they charge any fees for part of the school day for kindergartners. Questions on full- or part-day preschool, the location of those classrooms and which children they serve would also be removed.

The comment period on the proposed changes is over, but funding for the 2020-21 survey has not yet been approved. Democrats and some researchers have argued that DeVos’s proposed revisions would make it harder to monitor whether schools are suspending and expelling children before they reach kindergarten.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)