Closing the Digital Divide: Inside Cleveland’s Plan to Treat Broadband Like a Public Utility Service — and to Pay for Every Student to Get Online

The Cleveland school district is in talks to permanently solve a major problem facing schools nationwide in the COVID-19 crisis — internet access to students — by making it a free public utility.

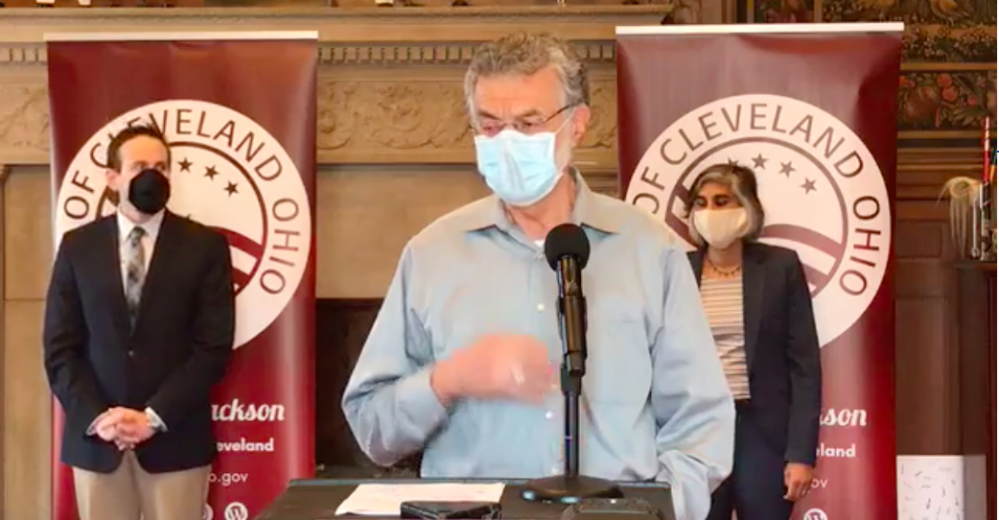

School district CEO Eric Gordon is working with local nonprofit DigitalC to treat internet access as a public service available to all, just like electricity, water and sewers. Gordon’s goal is to create a public utility that brings the internet to the poorest neighborhoods and students so that they have the same access to resources as affluent and connected suburban students.

If plans go forward, the district would pay $16 per month per home to connect every district family to internet service by 2022 from the new and growing EmpowerCLE+ system DigitalC is building.

The rapid school closures forced by the COVID-19 crisis have sent districts across the country scrambling to find ways to connect students to online lessons. That has meant passing out laptops and tablets to students, as well as finding ways to connect students online. Connection needs were strongest in cities like Miami, Detroit and Memphis, where more than a quarter of students have no internet access at all, according to the U.S. Census data and a 2018 study by the National Digital Inclusion Alliance.

In Cleveland, school officials say the need is great in a system where 100 percent of students receive free school lunch — a measure of poverty — and 44 percent of homes have no broadband service beyond data plans on personal cell phones. Cleveland is the fourth-worst-connected city in the nation, according to U.S. Census data and a 2018 study.

“If we think of this as a public utility and an infrastructure investment, and not simply a for-profit strategy, which makes it a luxury, we can get to solutions,” Gordon said in a recent talk to the City Club of Cleveland.

The partnership would be a rare one in the United States, at least on a citywide scale, according to digital access experts, and a possible model for other school districts across the country.

Gordon said it acknowledges an inequity that existed long before the pandemic: The internet has become an essential part of life. As chair of the Council of the Great City Schools, the national organizations of big-city districts, he hopes the crisis is the catalyst to make other districts and the federal government treat the internet as a worthy public service investment and close the divide.

“We use this as an opportunity to once and for all solve a national problem,” he said.

Although Gordon has not yet made the full plan public, City Council President Kevin Kelley said he supports bringing low-cost internet access to the entire city, as does Mayor Frank Jackson, who has already asked City Council to support the first step.

“In response to the pandemic, we sent our children home to learn remotely, knowing that approximately 12,000 scholars had no internet access,” Kelley said in an op-ed. “Our employers sent their workforce home to work from home when approximately half of Cleveland homes lack access to high-speed broadband. This must be a call to action to solve a problem that has been hindering our progress for over a decade.”

Connection issues were a major reason why Cleveland was slower than neighboring schools to pass out laptops and portable hotspots to students after schools across Ohio closed March 16 because of the COVID-19 crisis.

Digital C’s network would wipe out that obstacle, though the district would still need to make sure students permanently have access to laptops and are taught how to use them.

DigitalC’s plan calls for connecting 1,000 households that have district students by Aug. 31, then 8,400 more by May 2021. By 2022, all 38,000 students would have service from DigitalC. That’s projected at about 16,000 households, at an estimated 2.2 students per household.

That will take a rapid expansion of DigitalC’s network, which started a few years ago serving only a few public-housing complexes.

It started adding families as paying customers after the county allowed it to broadcast signals in the city’s Fairfax neighborhood from atop the county’s nine-story juvenile justice center late last year. The service is now growing in parts of the Glenville, Hough, and Woodland Hills neighborhoods on the city’s East Side with the Buckeye-Shaker neighborhood coming soon. It will start service Memorial Day in the Clark-Fulton neighborhood on the city’s West Side.

DigitalC has launched a $36 million fundraising campaign to cover the full city by 2022, said Angela Thi Bennett, DigitalC’s administrative director.

“It may not be municipal broadband, but it’s a partnership with the city to make sure our residents are not left behind,” Bennett said.

Gordon said the reduced $16 per month charge for DigitalC is $4 less per month than the district is paying now for hotspots.

“I can actually be the customer that builds the volume so that our kids and families get connected,” he said. Along with making costs work for Digital C, he said, families won’t have to worry about paying internet bills or being denied service because of poor credit or lost jobs. Immigrant families that are undocumented won’t have to worry about attracting notice.

“The fact that we become the customer takes that fear off the table, of ‘Will this be used to find me and deport me?’” he said.

Bennett said the district’s commitment helps DigitalC prove to donors that there is demand.

“Instead of an ‘If you build it, they will come,’ they’re here,” said Bennett, best known to residents as a former member of Ohio’s state school board and founder of a now-closed charter school.

The district would also make its school rooftops available as transmission points for DigitalC, with the city also likely allowing use of city buildings and poles of Cleveland Public Power, the municipal electric utility. The local public-housing agency, the Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority, is also on board.

Jackson has already asked City Council to support the first step. He has proposed giving $500,000 from the city’s Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) grants to DigitalC to add the first 1,000 school district families this year.

Director of City Planning Freddy Collier told a council committee last week that as many as 47,000 households in the city have no internet for job searches, medical care and other services beyond school. But he said that “that’s a bigger conversation” for later, while students need access now.

“We see this as an immediate opportunity to help stop the bleeding and also continue to move us along a trajectory of being able to provide wider access to the greater Cleveland community,” he said.

Several challenges remain. Raising $36 million isn’t easy in a pandemic-created recession. Wiring each house costs roughly $500, so the constant moves of highly transient students in the district can create unexpected costs.

The state has also not offered help toward wiring cities yet and is already slashing funding for state departments and to districts across the state. Gordon has suggested taking money the state has set aside for school construction projects and diverting that to internet infrastructure, at least in the short term.

State Sen. Matt Dolan, who chairs the state’s Senate Finance Committee, said that would take a law change and would anger many districts who have been waiting in line since 2001 for their turn at state aid for replacing old buildings.

And there’s no plan yet for covering monthly costs of other poor residents or students who attend non-district schools. Along with the 38,000 students in the district, 27,000 others attend private or charter schools.

John Zitzner, a founder of the Breakthrough charter school network, said some of his families are already connected through the DigitalC system, paying the standard monthly $18 fee themselves. He said he’d have to see a detailed plan before deciding if his schools would pay monthly costs for its students.

City Councilman Anthony Brancatelli, who represents the Slavic Village neighborhood where the district has closed several schools, said at a hearing last week that excluding schools like Cleveland Central Catholic High School in his district from help from CARES money isn’t fair.

“Leaving out and segregating a completely different population that’s not going to CMSD makes it that much harder to reach some of the most vulnerable populations that we have,” he said.

Collier said families that choose other schools can still save money using the $18-per-month service and that the city may be able to help using future federal grants.

“The need is always bigger than the capacity to handle it,” he said. “The only thing we can do is continue to move forward.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)