Native Leaders Urge Washington Schools to Implement Tribal History

The program is required under a state law passed eight years ago but still hasn’t been fully adopted.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Miranda Lopez remembers when she first learned about local Indigenous activist and athlete Rosalie Fish. Fish, a University of Washington runner from the Cowlitz Tribe, is nationally known for dedicating her races to Indigenous women who are missing or murdered, including her aunt.

Lopez is from the same part of eastern Washington where Fish’s aunt is from.

“It was eye-opening. I didn’t realize that this really big issue is happening right where I grew up,” Lopez said. “It breaks my heart.”

The class Lopez took where she learned about Fish is part of a decades-long effort in Washington to implement a K-12 Native studies and history curriculum known as Since Time Immemorial, which requires districts to create Native studies curricula in partnership with the tribes around them. It’s endorsed by all 29 federally-recognized tribes in the state.

When Lopez entered her senior year, she had no idea what she wanted to do next. So she spent a lot of time thinking about what she cared about, and what came to mind was her Native history class. Now 19, Lopez plans to become a Native studies teacher.

“From that point forward, that was my purpose for my future,” Lopez said.

Since Time Immemorial is important to students like Lopez — but non-Native students, too, should be learning about the communities they live among, said Willard Bill Jr., assistant director of the state’s Office of Native Education within the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction.

“It’s primarily to educate the broader…public school kid, so that when they graduate, they have a better understanding of what sovereignty is, what a reservation is, what does that mean, all the intricacies,” Bill said.

Although the Legislature mandated the curriculum in 2015, no deadline has been set for implementation. And while some districts are partnering with tribes to implement the curriculum, other tribal leaders told state officials they’ve struggled to get their school boards to comply.

Legislation sponsored by state Rep. Debra Lekanoff, House Bill 1332, would set minimum standards, a deadline for implementation of Since Time Immemorial and clear the way for state grants to help develop curricula. It failed to pass in this year’s legislative session. State officials say they’re optimistic about its chances in the upcoming session, which begins Jan. 8.

Efforts to implement

According to a 2022-2023 school year report from the State Board of Education, around 80% to 90% of school districts are incorporating tribal history and culture in their social studies programs. That’s a big jump from the last report from the 2021-2022 school year when 44% of districts reported having yet to implement tribal history and culture into their social studies curricula.

But without minimum standards, Henry Strom, executive director of the state’s Office of Native Education, said it’s difficult to know how many schools are providing quality Since Time Immemorial curricula because the original 2015 legislation did not set minimum standards. That’s why HB 1332 is important, he said.

At a meeting last month between tribal and state governments, Gov. Jay Inslee asked Suquamish Tribe chair Leonard Forsman how many districts were “cutting the mustard” when it came to implementing Since Time Immemorial.

“I think we’re probably under a third,” said Forsman, also a University of Washington board of regents member. He said the actual statistic may be lower.

“So that’s not exactly a success,” Inslee responded.

In the 2022 report, some officials in districts that had not yet implemented Since Time Immemorial reported that their districts had not updated their overall social studies curriculums.

“A district could, in theory, choose to delay the onset of a social studies [curriculum] adoption if they weren’t inclined to support Since Time Immemorial,” Strom said at the meeting where Forsman and Inslee spoke.

The work to create and implement Since Time Immemorial began in 1989, said Bill, whose father was one of the first tribal leaders to work on the curriculum. Tribes started funding the work in 2003, and the first legislation “strongly encouraging” implementing the curriculum came in 2005.

“This is some legacy work for us that we’re carrying on,” said Bill, a member of the Muckleshoot Tribe.

‘Place-based’ curriculum

Studies of school programs across the country indicate that teaching Native history to Native students often improves their educational outcomes. Native students have the lowest graduation rate in Washington state compared to other races and ethnicities.

Lopez said she wasn’t that interested in school before taking the Native history class.

“I didn’t see myself in stories and books,” Lopez said. “So when you put something like this in front of students, especially Native American students…and you tell stories of successful people, it opens up a sea of opportunities for a child. It changes the way they look at life.”

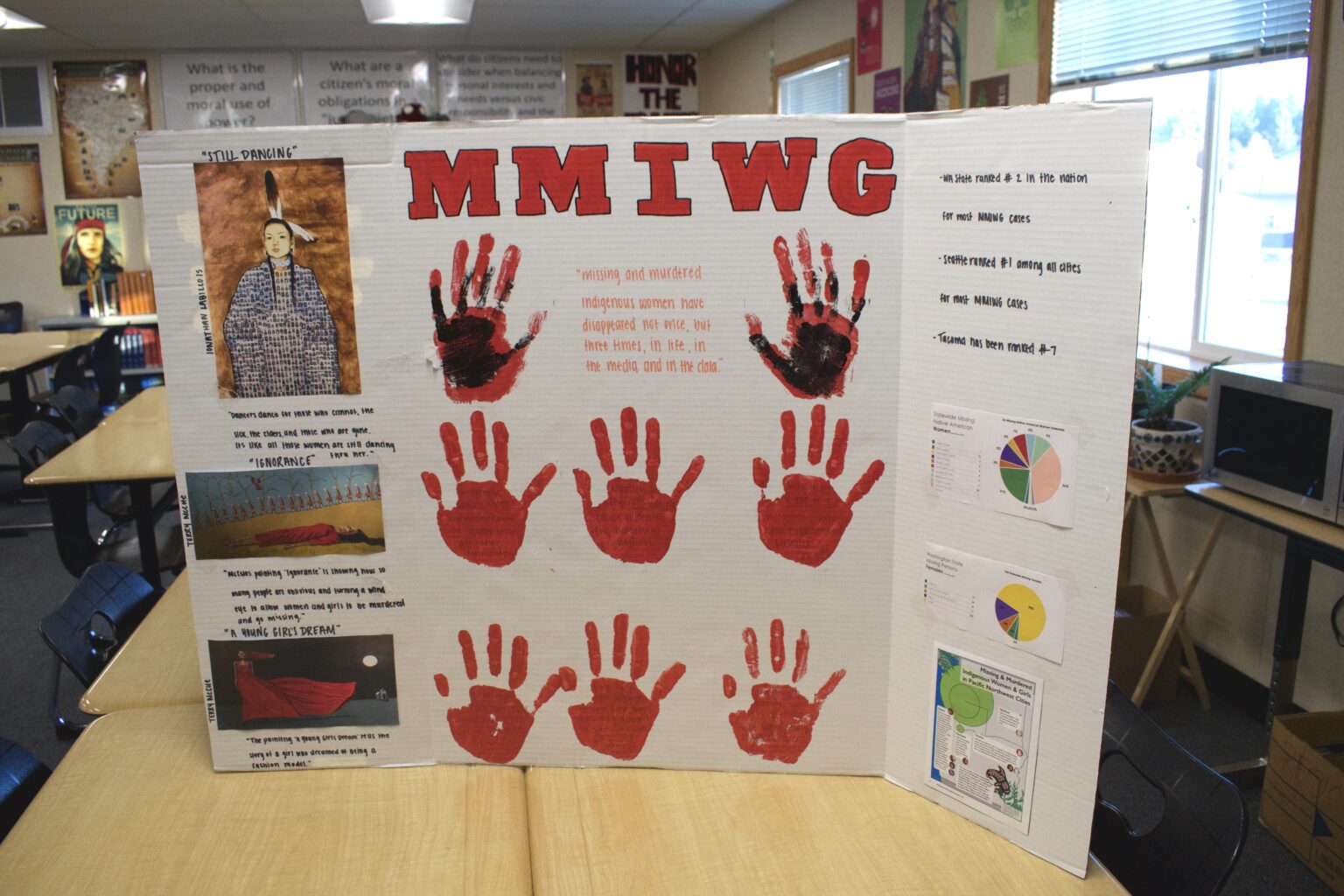

Today, 16-year-old Francheska Helton is taking the class Lopez first took: Alison McCartan’s 11th grade Native history class, taught at River Ridge High School. When asked what stories resonated with her, Helton, too, pointed to Rosalie Fish.

“I’m like, ‘I didn’t know that. How did I not know that? That’s someone from my tribe,’” said Helton, who is Cowlitz, like Fish.

Helton and Lopez learned about Fish because Since Time Immemorial is a “place-based curriculum,” meaning the focus is on the local indigenous communities who live on the land.

Since Time Immemorial also seeks to teach contemporary Native issues; A 2015 study found 86% of American schools teach Native studies in a pre-1900 context.

In McCartan’s class, students learned about an app created in response to the plight of missing and murdered Indigenous women. Then they talked about why many of them didn’t know about the app, and what could be done to both increase awareness and make it better.

McCartan said the issues they talk about vary within classes, but the main concept — teaching critical thinking about Native history and issues — remains the same.

In McCartan’s class, students also start the week sitting “in circle” and having a class discussion. It’s a traditional Indigenous way of learning that emphasizes a lack of hierarchy and community connection, and it’s not very common in an American high school environment, where learning is often more passive and lecture-based.

“Kids were resistant to it. They were like, ‘this is awkward,’” McCartan said. “But once they got used to it, the switch flips.”

McCartan said students open up to her and their peers in ways they never did before circle, and conversations in circle have led to Native students choosing to share about their own experiences and culture. One quiet Native student, McCartan said, even chose to speak at the school’s multicultural assembly because of conversations and support from his peers in circle.

“This is more than just a history class. It’s a community,” Helton said.

Tribal and school district relationships

The idea of Since Time Immemorial is that both Native and non-Native students will learn about who came before them, and who still lives on the land today, said Jerad Koepp, who runs River Ridge’s Native program. But Koepp said that many districts don’t ask the tribes around them, despite it being state law, leaving it up to tribes to appeal to school boards.

The relationship between North Thurston Public Schools, where River Ridge is located, and the nearby Nisqually Tribe is decades-long, said Bill Kallappa II, education liaison for the Nisqually Tribe and Washington State Board of Education member. However, the Native studies program at River Ridge began in 2019. Kallappa said having the tribal government-to-local government relationship is integral to the program’s success.

“Tribes aren’t in it just for tribal students,” Kallappa said. “Of course we want our kids to do well in the system. One way our kids can do well in the system is if we help improve the entire system for all students.”

Students in McCartan’s class said they knew “zero” about Native history before taking McCartan’s class, aside from the brief mention of what tribes exist in Washington in their middle school history textbooks.

“I think this [curriculum] should be taught in more schools,” said a non-Native student, 18-year-old Isaiah Kauhaihao-Derowin.

Obstacles and progress

McCartan, who is not Native, said she realized almost immediately that she didn’t have the knowledge to teach a Native studies program. She said she had to get used to saying “I don’t know.” In the beginning, Koepp was in her classroom almost every day, she said, and she leaned on his expertise.

McCartan’s situation was not unique. Strom says one of the biggest challenges to implementing Since Time Immemorial is a “respectful fear” among educators about getting it wrong.

Other obstacles have to do with bandwidth within schools, at the state level and among tribes.

The Office of Native Education has seen a surge in interest in its Since Time Immemorial teacher training, but only has 10 people on staff. Six years ago, there were just two people working for the office. Tribal leaders also say the financial burden to implement Since Time Immemorial shouldn’t be on the tribes. Currently, tribes often provide the funding and staff for curriculum development. Many smaller tribes aren’t able to do that, Kallappa said.

HB 1332 is meant to relieve some of that strain.

Koepp said non-Native educators can always turn to books, videos and other resources from their Native peers. “Just remember: we’re here and we’ve probably answered that question before,” Koepp said.

The outcomes of Since Time Immemorial at schools like River Ridge may be hard to quantify, but they’re visible through students like Lopez, who plans to return to St. Martin’s University in Lacey next fall to study secondary education focused on history, with a minor in Native perspectives.

Right now, she’s taking a break from school to search for scholarships and save up for the fall semester. After she graduates, she hopes to teach at River Ridge, within the Native studies program. And one day, Lopez wants to venture out to a school district elsewhere in Washington and create another Native studies program, just like the one at River Ridge.

“Native Americans are still here,” Lopez said. “Using a curriculum like this isn’t trying to remember them. We’re acknowledging them — as they are with us now.”

Washington State Standard is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Washington State Standard maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Bill Lucia for questions: info@washingtonstatestandard.com. Follow Washington State Standard on Facebook and Twitter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)