Native Boarding School Survivors Share Experiences and Healing at MSU Panel

Survivors, supporters and listeners filled an MSU auditorium this week in the hopes that by sharing difficult truths healing can continue

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

A room full of survivors, supporters and listeners, many donning ribbon skirts and orange shirts, filled an MSU auditorium this week in the hopes that by sharing difficult truths, healing can continue.

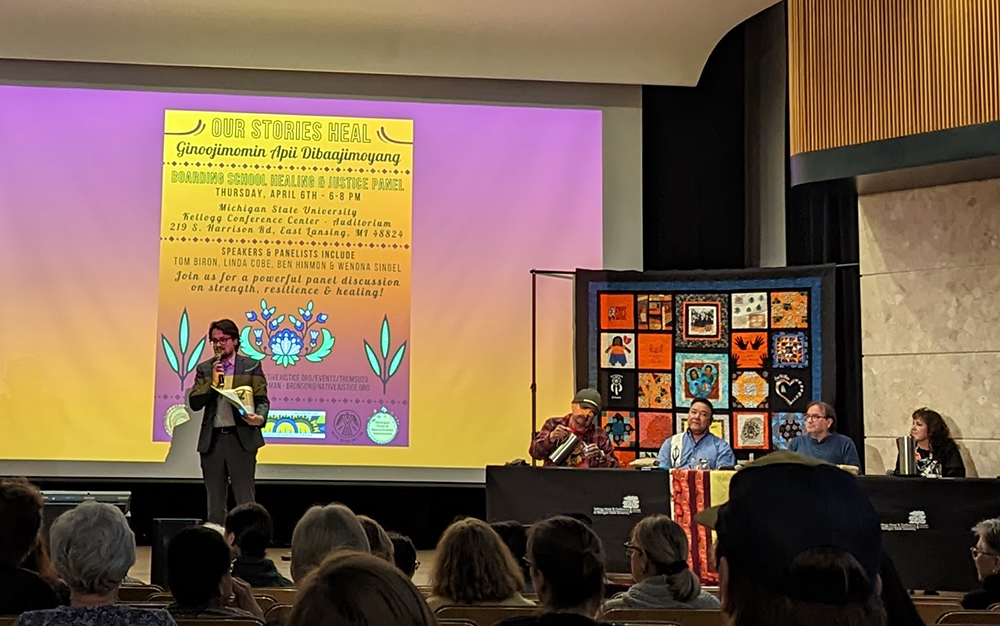

The boarding school healing and justice panel — titled “ginoojimomin apii dibaajimoyang,” which translates in Anishinaabemowin to “our stories heal” — was just as much of a ceremony on Thursday as it was a panel discussion. It encapsulated some of the Native Justice Coalition’s work to offer safe spaces for Indian boarding school survivors’ stories to be heard and for non-Indigenous people to listen.

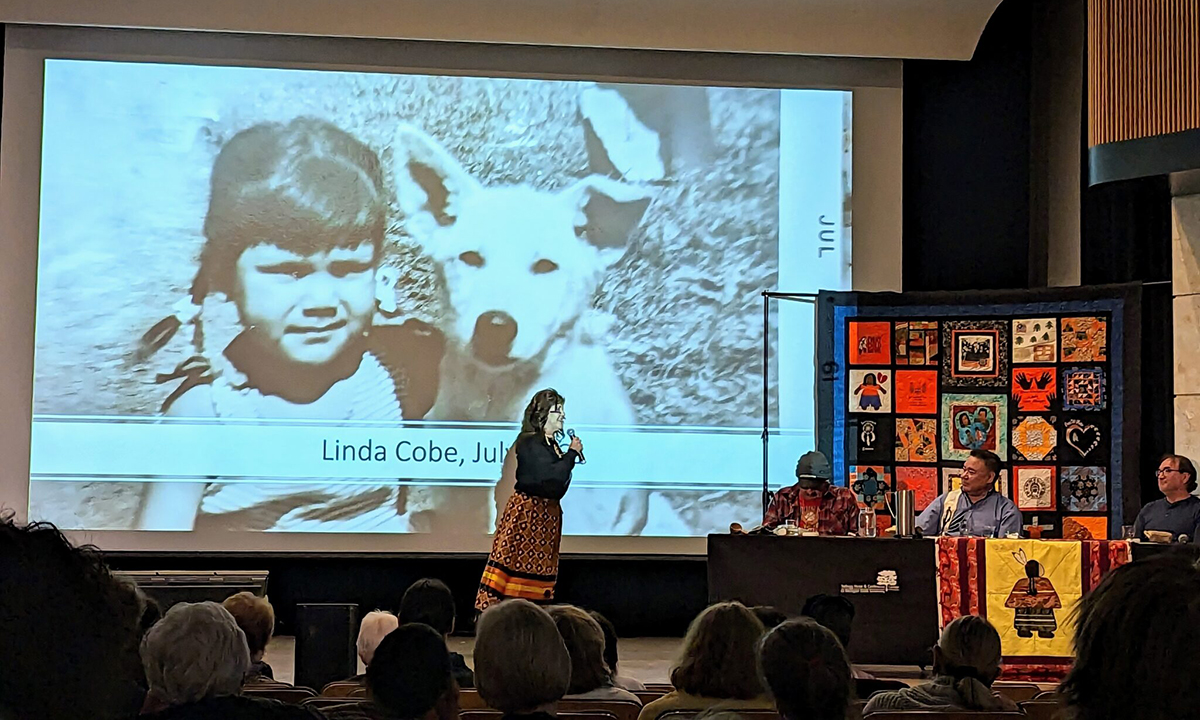

“I tell my story because I know there’s many out there who can’t,” said Linda Cobe, who is Ojibwe/Oneida and a Lac Vieux Desert tribal citizen. “… My language was taken from me, my childhood was taken, my culture was taken. But we have the opportunity today to get that all back.”

All three speakers on the panel, including Cobe, attended the Holy Childhood School of Jesus in Harbor Springs, known by many as the most notorious of Michigan’s five former Indian boarding schools. Differing accounts point to the northern Michigan school closing between the early 1980s to mid-1990s.

The event also featured Sault Ste Marie Band of Chippewa Indians citizen Tom Biron and Ben Hinmon, a descendant of Chief Pontiac who hails from the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe. The panel was cosponsored by the Indigenous Law & Policy Center, Native American Institute, and American Indian and Indigenous Studies at Michigan State University.

Five federally funded or operated boarding schools once operated in Michigan, according to a federal report released last year: The Holy Childhood School of Jesus; the Old St. Joseph Orphanage and School in Assinins (or Baraga Chippewa Boarding and Day School) near Baraga in the Upper Peninsula; the Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School in Mount Pleasant; the Mackinac Mission School (or Sainte Anne School) on Mackinac Island; and the Catholic Otchippewa Boarding School, or Otchippewa Day and Orphan Boarding, in the U.P.’s Schoolcraft County.

Thousands of Anishinaabe children in Michigan were forcibly removed from their tribal communities to attend that school and others, often many hours away from their tribe and family. In an attempt to assimilate the Indigenous children, their hair was cut, their clothing replaced with more “white attire,” their given names replaced with English names. They were pressured to exclusively speak English and were punished for speaking their own language.

On top of abuse, starvation, poor living conditions and sometimes death, this treatment of entire generations of Indigenous people resulted — as planned — with a significant blow to Indigenous identity, wisdom, language, customs and culture, survivors said.

It also came with deep intergenerational trauma that Native families and individuals still grapple with today.

“We have many children that experienced this horrific process have an inability to connect with who they were as Indian people and a loss of their identity as Native people,” said Wenona T. Singel, MSU associate professor of law, associate director of the Indigenous Law & Policy Center and a citizen of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians (LTBB).

Singel walked the audience through the historical context of boarding schools amid a slideshow of historic photographs depicting children who had been forced to attend the schools. She emphasized that the schools were part of the federal government’s “kill the Indian, save the man” policy for 150 years that presented a “cheaper” alternative to killing Native Americans in battle.

“These truths are so painful that many cannot share them during their lifetimes,” Singel said.

Under U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, there has been an effort since 2021 to reveal the depths of experiences at these institutions, marking the federal government’s first formal investigation and documentation of the boarding school system, decades after the last school stopped enrolling Indigenous children.

The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative seeks to compile records and information, make the historical truths widely available, and aid in the healing process for survivors and their families.

Bronson C. Herman of the Native Justice Coalition told the Advance that more of these panels are on the horizon in Michigan, where non-Native people are welcome to attend, listen and share what they have learned with their communities.

Michigan Advance is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Michigan Advance maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Susan Demas for questions: info@michiganadvance.com. Follow Michigan Advance on Facebook and Twitter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)