‘Nation’s Report Card’: Two Decades of Growth Wiped Out by Two Years of Pandemic

Long-term scores from NAEP show unprecedented declines for 9-year-olds in math and generational literacy loss

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

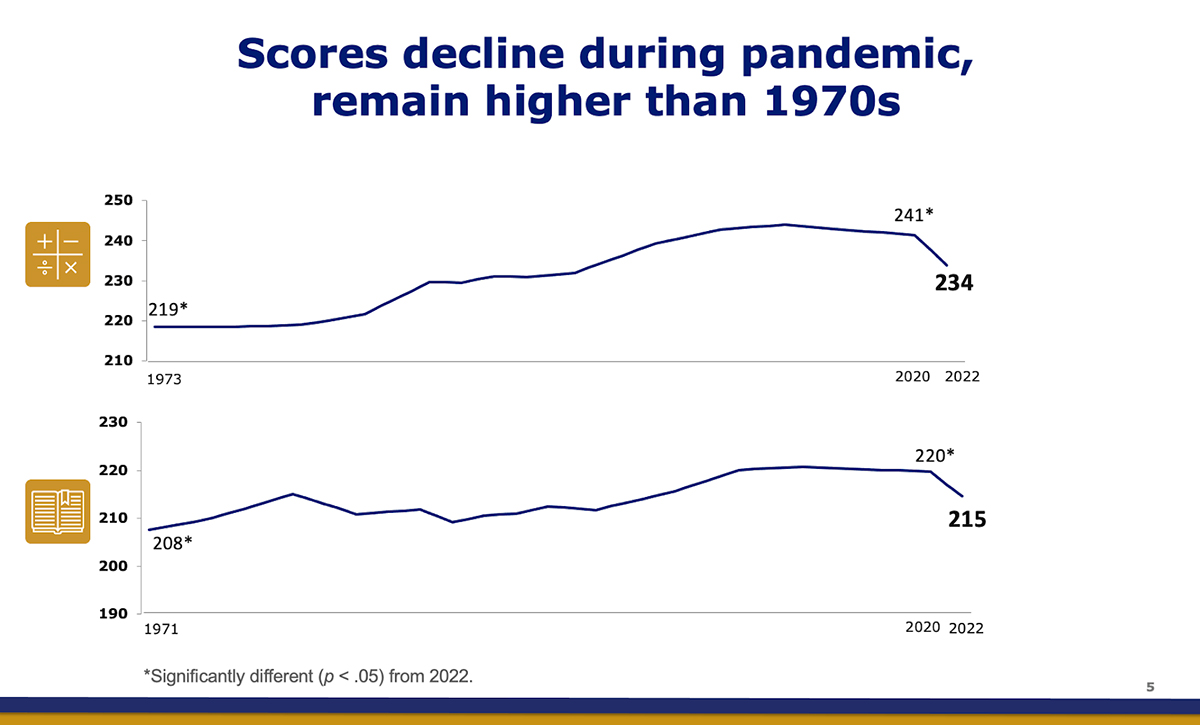

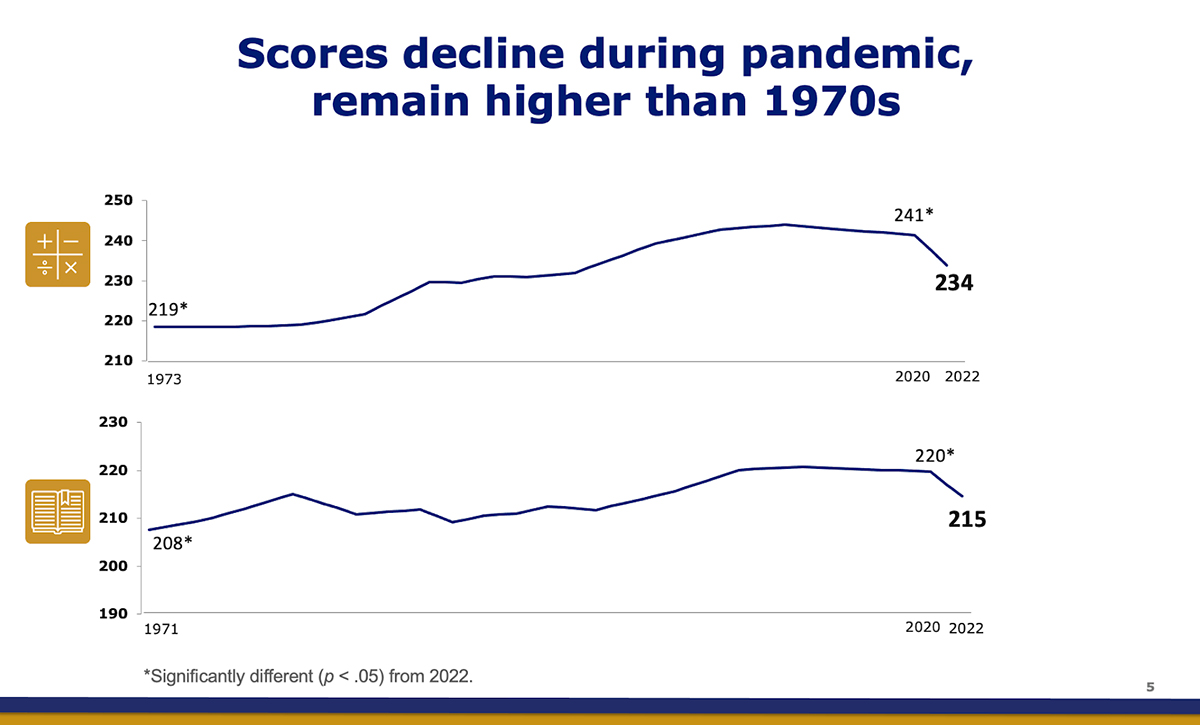

Two decades of growth for American students in reading and math were wiped away by just two years of pandemic-disrupted learning, according to national test scores released this morning.

Dismal releases from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) — often referred to as the “nation’s report card” — have become a biannual tradition in recent years as academic progress first stalled, then eroded for both fourth and eighth graders. But today’s publication, tracking long-term academic trends for 9-year-olds from the 1970s to the present, includes the first federal assessment of how learning was affected by COVID-19.

The picture it offers is bleak. In a special data collection combining scores from early 2020, just before schools began to close, with additional results from the winter of 2022, the report shows average long-term math performance falling for the first time ever; in reading, scores saw the biggest drop in 30 years. And in another familiar development, the declines were much larger for students at lower performance levels, widening already-huge learning disparities between the country’s high- and low-achievers.

The results somewhat mirror last fall’s release of scores for 13-year-olds, which also revealed unprecedented learning reversals on the long-term exam. But that data was only collected through the fall of 2019; the latest evidence shows further harm sustained by younger students in the following years.

Peggy Carr, commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics, said on a call with reporters that the “sobering” findings illustrated the learning losses inflicted by prolonged school closures and student dislocation.

“It’s clear that COVID-19 shocked American education and stunned the academic growth of this age group of students,” Carr said. “We don’t make this statement lightly.”

Average math scores for 9-year-olds sank by a staggering seven points between 2020 and 2022, the only such decline since the long-term test was first administered in 1973. Average reading performance — generally thought to be less affected by schooling than math, and therefore theoretically shielded from pandemic shock — fell by five points.

Inevitably, that means that fewer students hit the test’s benchmark performance levels than two years ago. For math, the percentage of 9-year-olds scoring at 250 or above (defined as “numerical operations and basic problem solving”) fell from 44 percent of test takers to 37 percent this year; those scoring 200 or higher (“beginning skills and understanding”) fell from 86 percent to 80 percent; even the vast majority scoring at the most basic threshold of 150 (“simple arithmetic facts”) shrank slightly, from 98 percent to 97 percent, across the two testing periods.

No demographic subgroup saw gains on the test, but disparities existed in the rates of decline. For instance, math achievement for white 9-year-olds dropped by five points, but for their Hispanic and African American counterparts, the damage was even greater (eight points and 13 points, respectively). As a result, the math achievement gap between whites and African Americans increased by a statistically significant amount.

In reading, scores for African Americans, Hispanics, and whites were all six points lower, leaving relative gaps unchanged. Scores for Asian students only fell by one point.

Notably, the long-term trend assessment differs somewhat from the main NAEP test administered every two years. It follows student performance going back a half-century, and it is taken with a paper and pencil instead of digitally. For the most part, testing items are unchanged from the early 1970s, assessing more basic skills of literacy and computation than are generally seen on the main NAEP.

The broad trend-line has been positive over the life of the exam, and even in the most recent release, student scores on both subjects are far higher than when they were first measured. But Dan Goldhaber, a researcher and longtime observer of student performance, said it was striking to see that upward momentum evaporate so quickly.

“A bit of a hidden story in education, when you look at a swath of 40 or 50 years, is the progress that students have made — and the disproportionate progress that historically marginalized students have made,” said Goldhaber, the of the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER) at the American Institutes. “We’re seeing a lot of that very long-term progress completely erased over the course of a couple of years.”

‘Particularly bad’

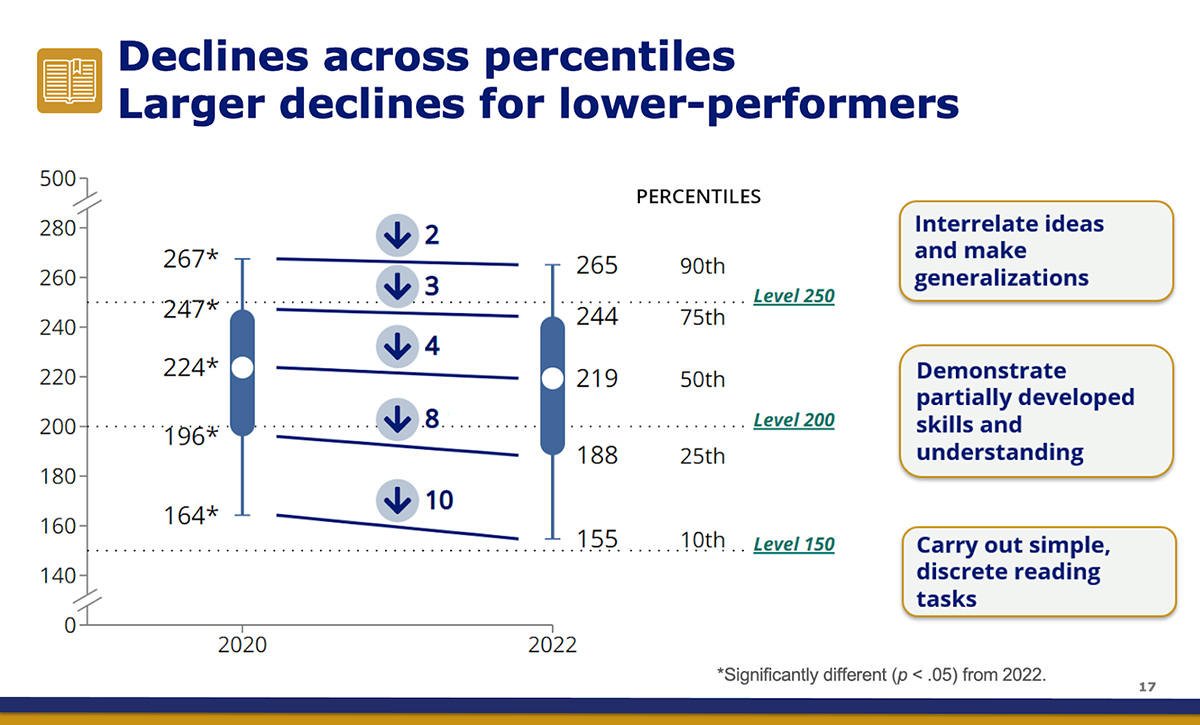

One of the most consistent, and consistently worrying, findings of previous NAEP rounds has been the sharp disjunction of students at either end of the performance scale. For over a half-decade, high-scoring students have generally performed a point or two better with each iteration of the test — or at least stayed at the same level — while low-scoring students have seen their scores fall.

The phenomenon of growing outcome gaps is again apparent in the post-COVID results, though it takes a slightly different form. At all performance levels across both subjects, 9-year-olds experienced statistically significant declines in their scores; but even with the identical downward trajectory, struggling students lost so much ground that disparities still expanded.

In reading, 9-year-olds scoring at the 90th percentile of all test takers in 2022 lost two points compared with their predecessors in 2020. But students scoring far below the mean, 10th percentile fell by 10 points.

Consequently, the average reading gap between kids at the 90th versus the 10th percentile grew from 103 points to 110 points in just two years. In math,the divergence grew from 95 points to 105 points over the same period.

Goldhaber said that the trends visible in NAEP performance largely dovetailed with those he and other researchers have identified using test scores from the MAP test, administered by the assessment group NWEA. In multiple data sources, he argued, it has become clear that the pandemic’s effects have been disproportionately negative for already struggling and disadvantaged children.

“It’s not just the drops, it’s where we’re seeing the drops in math and reading tests, and they’re disproportionately at the bottom of the test distribution,” he said. “So the pandemic is reversing a long-term trend of narrowing achievement gaps. That’s particularly bad, to my mind.”

The fact that losses are so heavily concentrated among the lowest-scoring segment of students may help explain what Goldhaber termed an “urgency gap”; neither states, school districts, or even families seemed driven to embrace the generational learning interventions — from dramatically lengthening the school year to implementing widespread one-to-one tutoring — that the scale of learning loss demands. As just one indicator, billions of dollars of federal COVID aid to schools remains unspent more than a year after it was first allocated.

That may change in the wake of the NAEP release. While previous studies have pointed to similar, and similarly inequitable, learning loss over the last few years by using data from the MAP and state standardized tests, the Nation’s Report Card is seen as the authoritative performance metric for American K-12 schools. As NCES Commissioner Carr noted, today’s release provides the first nationally representative results measuring achievement before and after the pandemic. Ninety-two percent of schools where the test was administered in 2020 were re-assessed earlier this year.

Tom Kane, an economist at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, agreed that NAEP scores definitively affirmed what prior studies have already demonstrated. More observers needed to study the magnitude of the loss, he added, because the proposed academic remedies in most of the country are “nowhere near enough” to combat it.

Kane analogized classroom learning to an industrial process — the conveyor belt slowed in 2020 and 2021, but has resumed functioning since at roughly the same rate as before the pandemic. But to make up for lost time, he argued, it would need to be sped even further.

“What we learned…is that the conveyor belt is back on, but at about the same old speed,” Kane said. “Somehow, we’ve got to figure out how to help students learn even more per year in the next few years, or these losses will become permanent. And that will be a tragedy.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)