More Disturbing NAEP Findings: Teens Don’t Read for Fun and Are Often Absent

Kelly: The latest Nation’s Report Card shows that helping students reach their full potential means supporting and inspiring them outside of school.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Over the past three years, students have grappled with unprecedented learning disruptions experienced during the pandemic. Numerous reports have shown significant declines in what students know and can do compared with pre-pandemic achievement levels. The National Assessment of Educational Progress — NAEP, often referred to as the Nation’s Report Card — has released results from five exams this past year, each showing troubling declines in student achievement. Now, results from a sixth test — the Long-Term Trend assessment taken by 13-year-olds in fall 2022 — show further drops in math and reading.

At this point, we as a country have a clear answer to one pandemic-fueled question: “What can America’s students know and do post-COVID?” Lost instructional time, combined with the tragic impact of the pandemic on the livelihoods and health of millions of Americans, has resulted in a cohort of students that are not matching the academic achievement of their predecessors.

What is less clear is how to answer a second, even more important question: “Where do we go from here to help all students reach their full potential?”

My answer to questions about how to improve student learning is centered on ensuring each child has a highly qualified classroom teacher, as research consistently shows teacher quality is the No. 1 in-school factor on student achievement. However, students spend far more time out of school than in, so the best efforts to boost achievement also require creative ways to support learning after the dismissal bell rings. How to do this can be informed by some striking results in student survey data accompanying the Long-Term Trend Report.

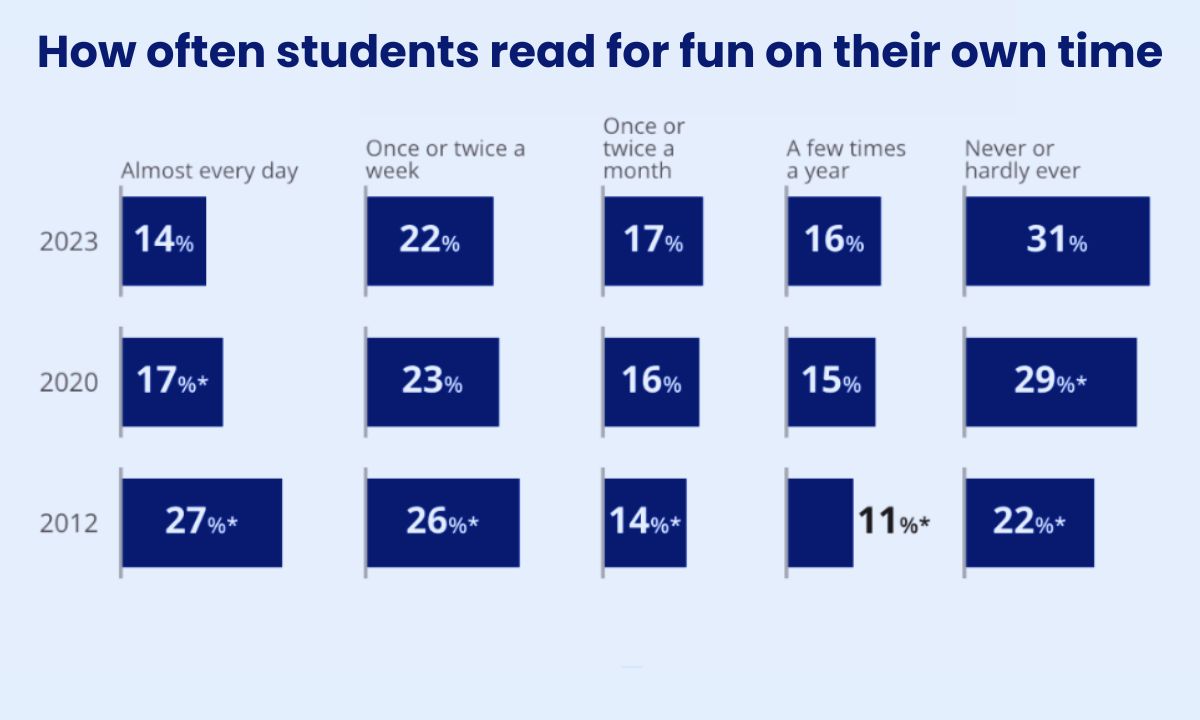

One shocking survey finding is that fewer and fewer kids read on their own, just for fun. A mere 14% say they do that daily, down 3 percentage points from 2020 and 13 percentage points from a decade ago.

Research shows that reading for pleasure produces benefits ranging from increased text comprehension to greater self-confidence. I have experienced these benefits personally, first as a kid in Tennessee reading the works of Tolkein and every biography I could find. It makes me sad to think about today’s kids missing out on the magic of a great book they picked out or that a friend recommended.

Today, I see the importance of reading for fun as an Advanced Placement U.S. Government teacher, as most of my top-performing students are also avid readers. And I’ve seen the value of reading as a parent of 12- and 15-year-old daughters who end nearly every day diving into a book they picked.

A second survey finding that has me worried has to do with chronic absenteeism, a problem that has worsened since the start of the pandemic. The percentage of students who say they missed five or more days of school a month has doubled since 2020.

These survey results illustrate big out-of-school challenges for students, meaning any hope of reversing academic trends will require greater collaboration between schools and families.

This has to start with making sure families are informed about their children’s progress, but many parents still don’t have great visibility into student data or a clear understanding of how their kids are doing academically.

In my own community, I see less family attendance at school events and less programming tailored to them than before the pandemic. In important ways, it’s understandable. Schools have a host of problems they didn’t have before, most notably serious and growing staffing shortages that force some things to get pushed to the back burner simply because educators are being asked to do everything.

Too often, schools are expected to have all the answers. But they can also tap families for ideas. For example, my family deploys a reading strategy at this time of year that we call reading bingo. My wife instituted the idea when our daughters were little, but they still enjoy it. Each girl gets a bingo card, and they have to complete the reading challenges on it. These can range from reading in a hammock to reading in a bathing suit, and the novelty spurs reading for pleasure. I’m sure other families have great ideas, and schools can facilitate opportunities for families to share these with one another.

Teachers alone can’t reverse chronic absenteeism, either. Young people are reporting increasing mental health challenges, and there is surely a connection between that awful reality and declining attendance. As a teacher, I’ve had to deal with students persistently missing class in recent years. I try to work with students and families in an empathetic way while balancing creative and flexible approaches with the need for accountability.

Policymakers and education leaders should prioritize the issue and family engagement as areas worthy of their time, attention and resources. They might look to community schools and other educational models with a track record of success in this area for ideas. As an example, Communities in Schools South Carolina is an organization demonstrating the power of bridging relationships among schools, students, families and neighborhoods in 39 high-poverty schools in order to, among other things, help students achieve regular school attendance.

The experiences of the past three years have shown conclusively that moments in school matter greatly for student achievement. But this latest Nation’s Report Card is a reminder that helping students reach their full potential likely requires rethinking how to support and inspire students in the moments beyond the school day, too.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)