Minnesota Dems Push to Repeal School Ban on Restraint That Killed George Floyd

'Prone kills kids,' advocate tells state lawmakers as they look to undo restraint ban that prompted police brass to pull cops from schools in protest.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This article is part of The 74’s EDlection 2024 coverage, which takes a look at candidates’ education policies and how they might impact the American education system after the 2024 election.

Updated, March 4

The Minnesota House of Representatives voted 124-8 Monday afternoon to approve legislation that removes a ban on school resource officers using prone restraint on students. The bill now moves to the Senate for consideration.

Nearly four years after George Floyd suffocated to death while being pinned face down to the pavement by a police officer, Minnesota Democrats are fast-tracking legislation that would undo a less-than-year-old ban prohibiting school-based cops from using that same type of restraint on students.

As early as Monday, the state’s House of Representatives is slated to consider a proposal that presents a drastic departure from provisions approved by Democratic Gov. Tim Walz — rules that explicitly barred school resource officers from using face-down “prone restraint.”

The ban was part of a broader police reform movement that followed Floyd’s murder. The fatal physical hold led to the largest civil rights protest in U.S. history, a national reckoning on racism, policy reforms that sought to address police brutality and, in Minneapolis and dozens of districts nationwide, the removal of sworn officers from school campuses. In Minnesota, new state rules barred police officers from using chokeholds on people and prone restraints were banned in the state’s prisons.

Now, as the state’s Democrats make a 180-degree turn on the campus reform, education equity advocates have accused state leaders of falling to the political pressure of law enforcement groups ahead of a November election where party lawmakers seek to maintain their narrow majority in the state House. The proposal cleared the House Ways and Means committee earlier this week.

Physical restraints have led to devastating consequences for children including injury and, in some cases, death. Yet for Republican lawmakers and law enforcement, the change in Minnesota went a step too far. Police departments statewide pulled their cops from schools in protest of the restraint restriction.

During a recent Senate Judiciary and Public Safety Committee hearing, Democratic Sen. Bonnie Westlin, lead sponsor of the Senate version of the bill that would restore prone restraints in schools, presented it less as a backtrack and more as an opportunity. The issue is about ensuring campus cops remain “important team members in our schools,” Westlin said, while creating uniformity across school resource officers’ duties, their training requirements and accountability.

Along with removing restraint rules for school-based police and campus security staff, the pending legislation would allocate $150,000 this year to develop consistent, statewide training standards for school resource officers and require police to complete the lessons before working on campuses. The bill also seeks to clarify that school-based police officers should not be involved in routine student discipline.

“When a local community determines that they would like to engage SROs, we want to make sure there is uniformity about expectations for everyone concerned,” Westlin said.

Advocates who lauded the prone restraint ban, however, say that lawmakers have turned their backs on Floyd’s legacy.

“How is it that — in the state where this man gets killed and the world erupted — that we are not the leading people who are banning this on our kids?” asked advocate Khulia Pringle, the Minnesota director of the National Parents Union and a steering committee member of the Solutions Not Suspensions Coalition, a group of education nonprofits that has lobbied against the legislation. “It’s banned in prisons, it’s banned for students with disabilities.

“Why can’t we extend that same courtesy to all children?”

The ‘fix’

Presented by Democratic leaders as an “SRO fix” bill, the proposal comes after police departments got wind of the restraint ban last fall — an under-the-radar change in a larger education bill that passed without opposition. In response, about 40 law enforcement agencies removed their school resource officers from campuses.

Under the language in the current law, school resource officers and campus security personnel are prohibited from using face-down prone restraints and “certain physical holds,” including those that restrict or impair “a pupil’s ability to breathe” or their “ability to communicate distress.”

The ban represented an extension of state rules that have been on the books for years. In 2015, after state education officials warned in a report that “it is only a matter of time before a Minnesota child is seriously injured or killed while in prone restraint,” lawmakers banned educators from using the technique on children with disabilities. Nationally, 37 states have laws that curtail educators from using prone restraints and other tactics that restrict students’ breathing.

In Washington, D.C., Democratic lawmakers have sought for years to pass a federal ban on student restraints. Nationally, about 35,000 students were placed in physical restraints at school during the 2020-21 school year, according to the most recent data from the Education Department’s civil rights office. Black students represented 15% of K-12 school enrollment and 21% of those placed in physical holds. Meanwhile, students with disabilities represented 14% of the national enrollment — and 81% of those subjected to restraints.

After the new changes were put in place in Minnesota and students returned to classes last fall, law enforcement agencies argued it stirred confusion among their ranks, opened their departments to lawsuits and tied their officers’ hands in how they work to keep schools safe and combat crimes like vandalism. Republican lawmakers seized on the furor and demanded a special legislative session to repeal the law.

Sign-up for the School (in)Security newsletter.

Get the most critical news and information about students' rights, safety and well-being delivered straight to your inbox.

The Coon Rapids Police Department, located in a northern Minneapolis suburb, is among the agencies that removed its officers from schools. That decision was reversed and the agency’s four campus cops returned to schools in November after the state attorney general issued a clarification on the law’s limits. The school resource officer program was put on hold temporarily last fall in part because of how officers are trained to do their jobs, Captain of Investigations Tanya Harmoning told The 74. She said she wasn’t sure how often prone restraint had been used by her officers inside schools. Regardless of whether an officer is stationed inside a school building or on a city street, she said, they “are all trained in the same tactics.”

“Our officers are trained a certain way to handle certain situations,” she said. “Some of these people transition back out onto the road, so to expect them to transition from ‘you can do it here, but you can’t do it here,’ kind of thing, that’s just not how we train our people.”

In two legal opinions last fall, Attorney General Keith Ellison clarified that the ban didn’t restrict officers from using prone restraints in cases involving imminent harm or death, which offered assurances to many law enforcement agencies that agreed to return officers to schools.

The special session that Republicans and police brass demanded didn’t come to fruition but the issue has become a top priority this year for Gov. Walz and his Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, which controls both chambers of the state legislature.

State officials and education leaders have sought to frame the debate as being not about prone restraint, but rather the need to get police back in schools.

‘The voices of all stakeholders’

When Democratic Rep. Cedrick Frazier appeared before the House Education Policy Committee in mid-February, he acknowledged the timing of his testimony: “We are not far removed,” he said, “from the tragic murder of George Floyd.”

He pivoted to a state law passed in response that banned police from using chokeholds — rules that he said were critical to their discussions about school-based police. With the chokehold ban in place, he suggested the prone restraint prohibition was unnecessary.

“The tension and anxiety that has been discussed, in large part, stems from the egregious visual of that tragic day,” Frazier testified. But even without a ban on prone restraints, he said that state law would continue to prohibit school-based officers from pinning students to the ground in ways that restrict breathing.

“Our only focus must be doing everything we can to ensure that while our young people are in our schools, that we ensure that their environment is safe from any type of harm,” Frazier said. “We must ensure our young people have the best environment to have the best possible outcomes.”

His testimony didn’t explicitly touch on prone restraints or why police needed greater autonomy around their use in classrooms. Representatives for Frazier and the governor didn’t respond to requests for comment and state Sen. Westlin’s office declined an interview request.

In his testimony, Education Commissioner Willie Jett focused on schools’ need for campus police officers and the bill’s new training requirements. He, too, didn’t touch specifically on restraint procedures.

“SROs are viewed by many as essential to maintaining safe and secure learning environments and data from the 2022 Minnesota student survey tells us that an overwhelming majority of students from all demographic areas value the SROs in their schools,” Jett said.

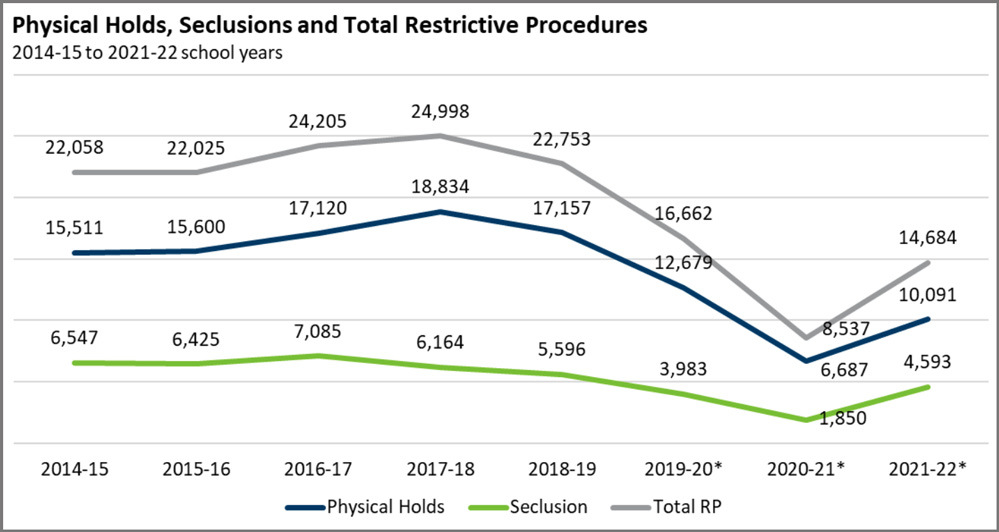

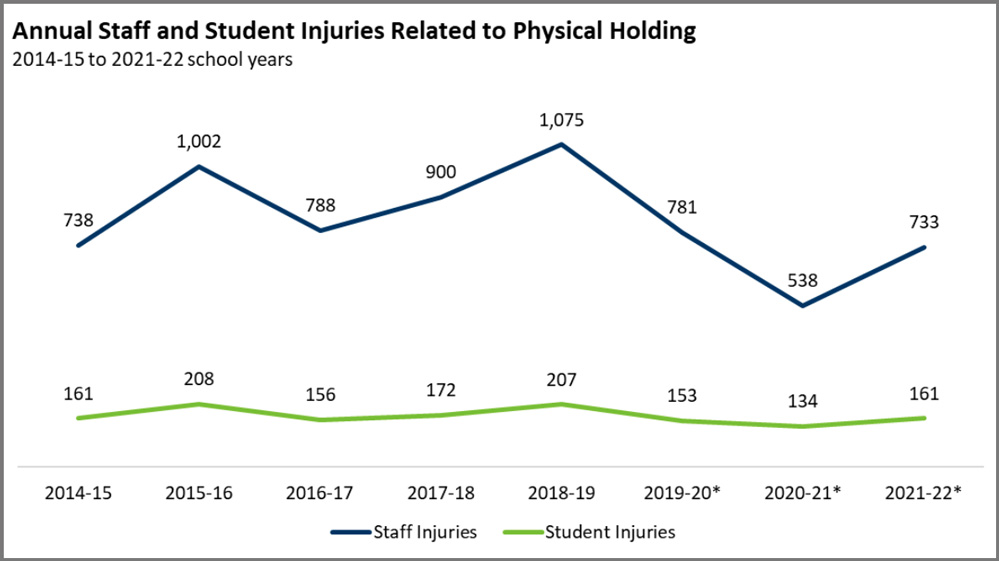

In Minnesota, state education officials have sought to reduce schools’ reliance on restraint tactics for years. The most recent state data on restrictive procedures reveal that students with disabilities were subjected to more than 10,000 physical restraints during the 2021-22 school year, with such holds disproportionately used on Black and Indigenous students. Frequently, state data show, these holds result in injuries — and more often for adults than children. During the 2021-22 school year, districts reported 733 staff injuries from placing students in restraints — a rate that equates to about one staff injury for every 14 physical holds. That same year, 161 students were reported injured.

Frazier’s work leading the reform bill appears to be at odds with his broader championing of policing and public safety. After Floyd’s murder, Frazier became known in the state as a key negotiator in favor or progressive police reforms, often drawing on his personal experiences with inequities growing up as a Black teen on Chicago’s South Side. In September, as police agencies statewide began pulling officers from schools, Frazier signaled his support for the new prone restraint ban. The House People of Color and Indigenous Caucus, which Frazier co-chairs, released a statement expressing that same sentiment.

“The provision in the education bill passed earlier this year related to school personnel is clear: School staff, including school resource officers, are not allowed to use prone restraints,” or other holds that restrict a student’s ability to breathe, the caucus wrote in the statement, which bore Frazier’s name. Given the attorney general’s opinion extending SROs’ authority to restrain kids in serious cases, the group wrote, “changes to the law are not needed.”

In Republican’s unsuccessful bid to force a special legislative session, they found common ground with Education Minnesota, the state teacher’s union, which noted that school staff needed clear guidance on how to protect themselves and students during potentially dangerous situations. In 2021, union spokesperson Chris Williams told The 74 the group was concerned about “the ongoing racial disparities that we know exist in the use of restrictive procedures,” and noted support for rules that prohibited prone restraint in classrooms.

Williams didn’t respond to a list of questions about the pending legislation introduced by Frazier who, along with being a state representative, works as a teacher’s union staff attorney.

‘Prone kills kids’

When Matt Shaver testified at the House education committee last month, he opened with a grim warning: “Prone kills kids.”

“We are advocates for kids — and prone kills kids,” said Shaver, the policy director of the nonprofit EdAllies, which is a member of the Solutions Not Suspensions Coalition working to maintain the current prone restraint ban. “This is not about whether SROs belong in schools,” as lawmakers and state education officials have cast the conversation, he said. “This is about whether we believe holds that kill children belong in school.”

Shaver cited a recent study which examined childhood fatalities that stemmed from physical restraints over a 26-year period. Researchers identified 79 incidents where restraints led to deaths in settings including foster homes, psychiatric agencies and schools. Deaths were most common when children were held in the face-down prone restraints — and most often for benign childhood behaviors like failing to remain silent or sit without wriggling. Investigations into the fatalities found that adults routinely failed to follow proper restraint policies and laws.

“In 15 fatalities, children vomited, urinated or turned blue during the restraint,” researchers concluded in the 2021 study, which was published in the academic journal Child & Youth Care Forum. “These signals should have been detected by an adult monitoring these events and immediately triggered a change in tactics or discontinuation of the restraint.”

Shaver told The 74 he believes the Democrats are reacting to the politics of the police “work stoppage” and a desire not to appear soft on crime ahead of the November election. That has placed them in the position, he said, of wanting to overturn the restraint restriction, but “not in a way that will freak out their base.”

“They may have failed at doing that,” Shaver said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)