McCracken: Why Apple’s New Push Into Schools Has Less to Do With Dethroning Chromebook Than Wooing a New Generation of Hearts & Minds

Apple couldn’t have picked a better venue for the education-themed media event it held in late March. Instead of summoning members of the largely Bay Area–based tech press to the Steve Jobs Theater at its new Cupertino headquarters, it convinced them to schlep all the way to Chicago to visit Lane Tech College Prep High School, a highly regarded magnet school in an improbably well-preserved 1934 building.

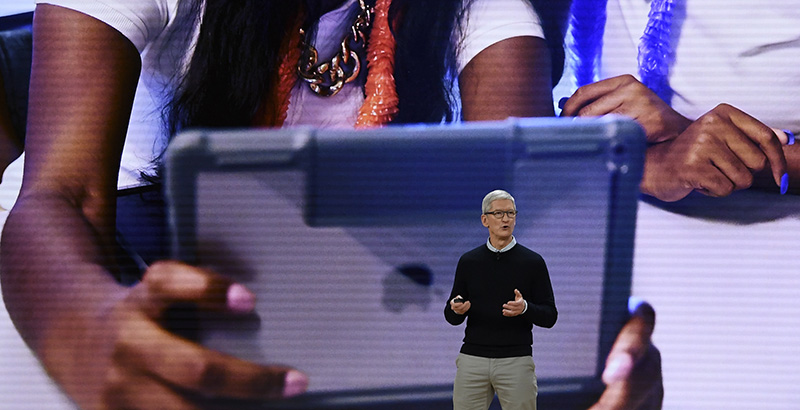

Attendees, including me, squeezed into seats in the auditorium to watch CEO Tim Cook and other executives give a presentation that was as much about reinforcing Apple’s love of education as the product announcements, which included a new iPad and a raft of software and services aimed at students and teachers. Then we dispersed to classrooms to get some hands-on time with the just-announced offerings, led by members of the company’s education team.

As Apple obviously hoped, this back-to-school experience was inspiring. But when it was over, reality resumed. And for Apple in 2018, the reality of the education market is pretty ugly.

In 1976, Steve Wozniak gave the very first computer produced by the tiny startup he founded with Steve Jobs to a junior high school algebra teacher. Throughout the Apple II and Mac eras, the company was the dominant force in classroom computing, a fact that was good for both its bottom line and its corporate soul.

Today, however, the archetypal classroom computer is a Chromebook, based on Google’s nine-year-old Chrome OS platform. Chromebooks held 60 percent of the market for mobile computing devices shipped to U.S. K-12 schools in the third quarter of 2017, according to research firm Futuresource Consulting. Between iPads and Macs, Apple had just 17 percent.

Chromebooks have taken off in part because they’re cheap, starting at under $200, versus the $299 education price for Apple’s new iPad. (The cheapest MacBook is $849.) Their familiar laptop-style cases and physical keyboards lend themselves to test-taking and other tasks involving typing, which matter as much to schools as ever. Perhaps most important, Google offers a robust suite of cloud-based services for everything from word processing to website building to assignment distribution and communication with parents — all available from any device a student or teacher signs into, and all free.

Apple barely mentioned Chromebooks by name during its Chicago event, but certain aspects of its news clearly aimed to scratch the same itch that Google has addressed so successfully. For example, it introduced Schoolwork, an app that will let teachers assign reading materials to students via iPad and even direct them to a specific section of an app, using a new technology called ClassKit. (There are 200,000 education offerings in Apple’s App Store.) The company also unveiled a $100 rugged keyboard case — manufactured by accessory kingpin Logitech — that converts an iPad into a more laptop-like form, optimized, like a Chromebook, for typing.

But for every instance of Apple seeming to acknowledge an area where Google has a lead and attempting to narrow it, there was another where it played up factors that make iPads unique. Chromebooks are unabashedly utilitarian; the iPad, declared Apple executive Greg Joswiak, is “a magical sheet of glass that can become anything we want it to be.” When he said that “today, learning happens everywhere, even where there might not be a desk,” and showed a picture of a kid using an iPad to shoot video of foliage for a school report, he didn’t have to add, “You can’t do that with a $200 Chromebook” for his point to be clear.

Along with capturing and editing video, iPads excel at allowing kids (and everyone else) to work with photos, make music, draw, and paint — none of which are particular strengths of Chromebooks. Instead of cutting the price of the new iPad to better compete with Google, Apple kept the cost the same and added support for the iPad Pro’s Pencil pressure-sensitive stylus, which turns this entry-level device into an even better tool for artistic endeavors. (Not that creating art is the Pencil’s only purpose: One onstage demo showed it being used to dissect a virtual frog using Apple’s augmented-reality technology.)

From Apple’s perspective, the iPad’s focus on creative self-expression doesn’t limit the breadth of its usefulness as an educational tool. For instance, the math section of the Chicago event’s classroom sessions didn’t involve doing math; instead, attendees wove photos, music tracks, and voice-overs into a mini-movie about the Fibonacci sequence. This fall, the company even plans to offer “Everyone Can Create,” a new iPad-centric curriculum which will complement “Everyone Can Code,” its existing coursework for teaching kids programming skills.

As engaging as all this is, much of the reaction to the Chicago event from people who care about educational technology was measured at best and skeptical at worst. That’s a reminder that Chromebooks are now as deeply entrenched as Apple devices once were. Then again, Apple doesn’t need to steal back most of the market share it’s lost to thrive. With Macs and iPhones, it’s already perfected the art of turning an enviable profit from products whose market share is piddling compared to the competition’s (Windows PCs and Android phones, respectively). It can presumably do the same by selling $299 iPads to schools.

Still, Apple’s interest in education has never been solely about products and profits. The company’s presence in classrooms has enriched society. And it’s done it in a way that makes real its contention that its business sits at the intersection of technology and the liberal arts, an allusion that Steve Jobs was fond of making and which Tim Cook brought up during his Lane Tech presentation. Along the way, it’s also introduced countless young people to Apple’s hardware and software, helping to predispose them to be Apple fans once they headed to college and then into the workplace.

Back in 2001, Jobs gave a keynote speech at the National Educational Computing Conference in Chicago. “We’re in education not just because we want to make revenue and profits, although that’s important, but because we give a damn, just like you guys,” he told the audience. Seventeen years later, in the same city, Apple showed that it still does — but it will take more than a single event to ensure that education gives a damn back.

Harry McCracken, technology editor at Fast Company, has written about computers since the glory days of the Apple II.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)