Lake: With New COVID-19 Variant, Reopening Schools in Next 100 Days May Not Be Possible. We Must Plan Accordingly, Not Put Our Heads in the Sand

A new, more transmissible COVID variant has been found in more than 20 U.S. states. This and other variants emerging around the world have made it harder for epidemiologists to predict the course of the pandemic, or how effective vaccines will be.

This uncertainty has clear implications for education. Our nation’s strategy to address learning loss and the pandemic’s gut-wrenching mental health toll on young people cannot rely solely on reopening schools.

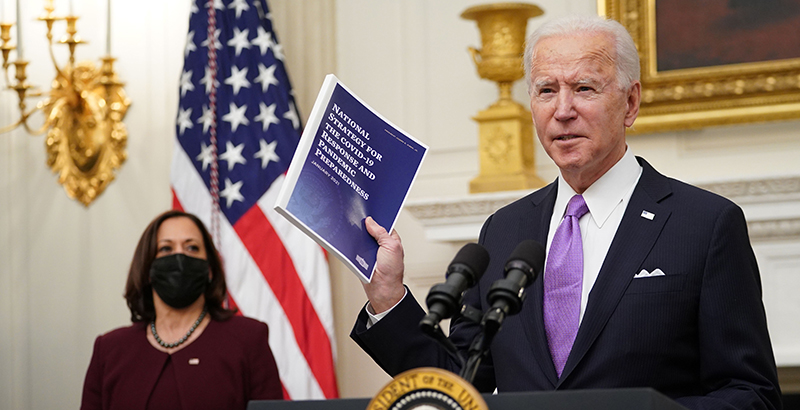

I have been a strong advocate for safe school reopening. I’ve argued that science, not fear and politics, should determine when it is safe for kids to be in classrooms. But I am now concerned that it will be difficult, if not impossible, to achieve President Joe Biden’s goal of having most schools open within his first 100 days.

We must prepare for that possibility and plan accordingly, not put our heads in the sand.

Though many school districts have opened successfully this year, we missed critical opportunities to bring students back to school last summer and throughout the fall. This was mainly due to pressure from teachers unions that led to overly cautious state and local metrics for reopening. With a new administration in place and vaccines rolling out, the hope has been to get school buildings open.

Then the new variant came along in the United Kingdom. The latest evidence shows this variant is more transmissible by 20 percent to 50 percent and may hold an increased risk of death.

Schools in the UK are closing. Even Denmark, where children have happily attended in-person classes for most of the pandemic, is sending all but the youngest students home. Young children appear to be less susceptible to COVID-19 and less likely to transmit the virus. The science is still emerging, but the early consensus seems to be that this is still generally true with the UK variant. Young children appear to be about half as susceptible as adults, but the virus is more transmissible (by some estimates 25 percent to 50 percent more) by all age groups.

This means virus spikes and school-based cases are more likely, forcing schools to close to slow overwhelming transmission rates, even though they are not superspreaders.

Scientists estimate that the variant has been in the U.S. for some time, but until now it has accounted for less than 1 percent of cases. However, that is changing rapidly. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warns that this variant will be the dominant strain by March — bad timing for the administration’s laudable 100-day goal to reopen schools that will have been shuttered for a year.

I’m painfully aware of the academic and emotional costs of keeping schools closed. But now, here we are, banking all our hopes on the promise of getting kids back into classrooms.

We need to do everything within our power to reopen schools. My own two kids are scheduled to go back next week with a well-researched health and safety plan. I am prepared to send them and hopeful they can attend in person for the rest of the year. I want all students to have that opportunity.

But we also need to relinquish the currency of denial that has hampered school systems since March. We need to get realistic scenarios from the scientists and move mountains to address student needs.

We need clear federal guidance, driven by science, not state-by-state guesswork or politics, on when it is advisable for schools to reopen.

We need a national database, ASAP, that ties open/close status to COVID cases so we can understand in real time the relationship between in-person instruction and local transmission and what kinds of school safety measures are most effective. We should not be in a position of having to rely on studies from Europe.

We need to prepare to give school-age children what they most need in the next six months with the assumption they may not be in classrooms. High school students need to graduate. For them, we should ask: 1) what are the essential skills/knowledge they need to master this year? 2) what are the most creative (mostly online) ways to make sure they do? 3) what do we need to stop doing to make that happen?

That may mean dropping some content or courses for the rest of spring and redeploying teachers and all available adults to do small-group virtual or in-person tutoring. It may mean providing funds to parents to purchase online tutoring or other academic programs.

Students are struggling mightily with lack of motivation and depression. An alarming rise in suicide rates shows how desperate the situation is. We must deploy community mental health assets and social support to help them, whether they are at home or in school.

Young students are not learning much from virtual instruction and are missing critical social development. If it is not realistic to get them back into classrooms, we ought to furlough teachers and plan for summer school.

I hope I am wrong. I hope Biden can deliver on his 100-day pledge to open most schools. But it seems increasingly unlikely. This explosive new variant will be the prevalent reality soon, and others could emerge. We must press forward with vaccinations and open schools as soon as is safely possible. But we also have to plan for realistic scenarios and commit to meeting student needs wherever and however we can.

Robin Lake is director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington Bothell. You can find her on Twitter @RbnLake.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)