Korman: Mark Janus Never Sued Anyone, So How Did He Become the Face of the Year’s Biggest Court Case Involving Unions?

Mark Janus, child support specialist in the Illinois state family services agency, is challenging the state’s collective bargaining laws in a case that’s now before the U.S. Supreme Court. This case has potentially far-reaching implications, and oral arguments are scheduled for the end of this month.

When I was in law school, there were so many moments when I thought: “Why am I only learning this here, now, in law school? Everyone should know this stuff!” Civil procedure — the rules that govern the movement of lawsuits through the courts — is one of those things. So let me outline how Janus v. AFSCME got to the Supreme Court.

WATCH: Understand the Janus Case in 100 Seconds

The case started when Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner sued in federal court to challenge his own state’s union agency fee statute, the law permitting collective bargaining units to charge all represented workers for the cost of representation even if they opt out of the union. Rauner presented the same argument that Janus has since advanced: that the agency fee statute violates workers’ First Amendment rights.

The federal district court determined that Rauner’s office hadn’t been harmed by the law and therefore lacked standing to sue. But Mark Janus’s lawyers had filed papers to make him an intervenor in the case — an additional party who claims he has rights and/or injuries that are about to be adjudicated in an existing case. When the court dismissed the governor’s complaint, it recognized Janus’s complaint as the operative one, meaning the one that’s current or pending before the court.

What is Janus’s problem? Illinois state employees must be part of the bargaining unit that represents them and all similarly situated workers in their agency in collective bargaining negotiations and grievance processes. It’s a condition of Janus’s employment; even if he doesn’t want to join the union — in his case, the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees — he has to pay those agency fees to cover the costs of this representation.

He contends this arrangement is unconstitutional under the First Amendment because his employer is the government and it is compelling him to support speech he does not agree with — in this case, union negotiations. (At the same time, it’s notable that he doesn’t point to any specific union issue or position that he disagrees with, and there is no evidence that he made any effort to engage in the internal representative process of his collective bargaining unit to argue for his position.)

Janus didn’t have a trial to address his constitutional question about the First Amendment. After the district court accepted his intervenor complaint as the operative one (as someone who has paid agency fees, he could show he was personally harmed), the court reviewed the substance of his complaint and dismissed it. This is because there is already a Supreme Court ruling on exactly this question, Abood v. Detroit Board of Education. Decided in 1977, Abood held that as long as the collective bargaining unit didn’t charge people like Janus for its political activities, there was no First Amendment violation. Under the decision in Abood, Janus’s freedom to speak — or not to speak — wasn’t meaningfully infringed by his obligation to support his bargaining unit as a condition of employment.

But, as the losing party in that decision, Janus — now called a petitioner — could take his case to the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeal for review. And when he lost there as well, he was eligible to ask the U.S. Supreme Court to hear his case.

A request for review by the Supreme Court is made by submitting a legal brief known as a petition for a writ of certiorari. The court exercises what is known as discretionary review and selects only a very small proportion of cases submitted. If the court doesn’t hear a case, the court of appeal’s decision stands. The same is true if a Supreme Court case results in a 4–4 tie.

There are lots of reasons the Supreme Court might accept a case for review. Sometimes the case presents a novel question of law, sometimes the justices must resolve contradictory decisions from different circuit courts of appeal, and sometimes there is an issue the justices want to resolve but haven’t yet had the right case in which to do it. Janus is in the third category.

More from The 74

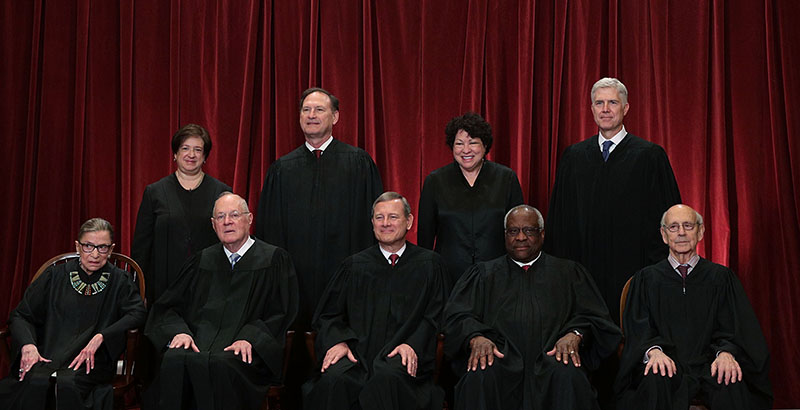

The court faced the same question raised in Janus in 2016, in Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association. That case resulted in a 4–4 tie, with no written opinion, after the unexpected death of Justice Antonin Scalia. The justices had made clear before Friedrichs that they were interested in reviewing the question of agency fees, and it was obvious to most observers that the question was still on the table.

That question, in legal terms, is “Should Abood v. Detroit Board of Education be overruled and public-sector agency fee arrangements be declared unconstitutional under the First Amendment?” That’s the question the Supreme Court accepted when it granted Janus’s petition for certiorari and will take up in oral arguments February 26.

This essay originally appeared in slightly longer form in Ahead of the Heard, a blog of Bellwether Education Partners. (Disclosure: Andrew J. Rotherham, a co-founder and partner at Bellwether Education, is a senior editor at The 74 and serves on The 74’s board of directors.)

Hailly T.N. Korman is a principal at Bellwether Education Partners on the Policy and Thought Leadership team, focusing on correctional education, justice-involved youth, and school discipline.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)