K–12 Leaders Love the Four-Day School Week, But a New Study Shows that it Doesn’t Do What They Hope

Research from Missouri reveals that dropping a day of instruction doesn’t improve teacher retention.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

In recent years, hundreds of school districts across the United States have responded to labor issues and straitened budgets by switching to a four-day weekly schedule. But new research from Missouri suggests that cutting out a day of instruction doesn’t yield the benefits proponents hope to achieve.

Circulated as a working paper on Monday, the study offers a statistical analysis of the effects of shifting to a shorter week alongside extensive reflections from educators themselves. Most of those teachers, principals, and superintendents spoke favorably about the change, saying they believed it had helped their schools attract and retain teachers in the midst of a tight job market.

The numbers tell a different story, however: On average, the 178 Missouri districts that adopted a four-day week since 2010 did not improve at either recruiting new teachers or retaining their veterans. Andrew Camp, a scholar at Brown University’s Annenberg Institute and one of the paper’s authors, said district leaders’ enthusiasm for four-day weeks was likely grounded in the sincere belief that they could be the answer to persistent staffing challenges.

“These things spread through word of mouth, they grab hold of people’s imaginations, and we end up with this rapid adoption of four-day school weeks,” Camp said. “But the fact that it was such a small effect — for a lot of these districts, it’s one teacher being retained every three years — was really striking.”

The almost negligible results, and officials’ apparent misapprehension about their true magnitude, are particularly salient given both the scale of the four-day phenomenon and the speed with which it has been embraced.

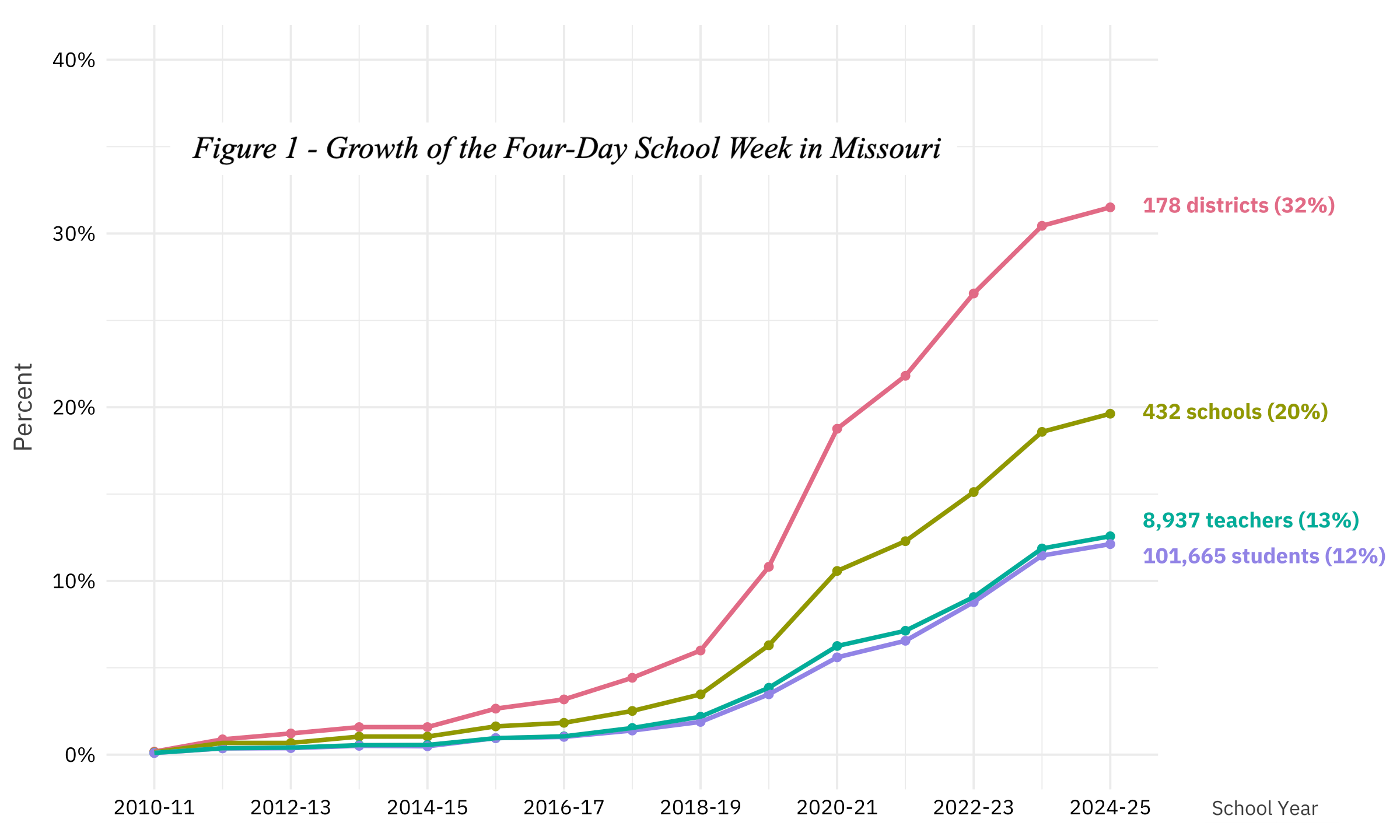

Mirroring national trends, the number of districts throughout Missouri operating on a shortened schedule has skyrocketed over the last decade and a half, accounting for one-third of the statewide total last year. Twelve percent of all students, and 13 percent of all teachers, now experience a four-day week (smaller figures proportionally, because they live almost exclusively in rural areas with smaller headcounts).

The initial wave of transitions, beginning in the early 2010s, is usually attributed to states’ need to contain education costs in the aftermath of the Great Recession. But in the study’s 36 interviews with leaders of Missouri schools and districts, along with several teachers, respondents generally agreed the main effect of the scheduling change was to slow turnover and make schools more attractive places to work.

This is something that's a potentially risky gamble, and there don't seem to be any benefits as far as teacher retention or recruitment.

Andrew Camp, Brown University

At least one superintendent credited the four-day week — which requires teachers to work longer days when school is in session, effectively holding instructional hours constant — with a surge in job applications and a sizable drop in workforce churn. Several others claimed that a longer weekend was a vital feature in drawing teachers to far-flung communities that cannot afford to offer top salaries.

But after examining state administrative data between the 2008–09 and 2023–24 school years, including figures on teachers’ school and district assignments, education levels, and experience, Camp and his co-authors found that four-day districts won only meager advantages. Switching to a truncated schedule resulted in just 0.6 job exits per 100 teachers, an effect that falls below the bar for statistical significance.

Camp said the findings were broadly in line with those of prior work on the four-day schedule. While the transition might prove appealing, especially to new teachers, it likely would not address most employees’ complaints about salary and working conditions.

“We don’t rule out the possibility that there is a short-term, very small bump in teacher retention and recruitment,” he said. “But what our results from Missouri show is that, over this lengthy period, there’s no lasting effect.”

Echoes past findings

It remains to be seen what effect, if any, the new paper will have on the ongoing debate around the often controversial policy.

On one hand, it can only be said to be representative of one state’s approach. Around the country, different legislatures and districts have permitted distinct versions of the four-day week. Unlike in Missouri, some states do not specify that overall instructional hours stay the same even in a shortened schedule, resulting in less instruction being delivered to students over the course of the school year.

In Oregon, where more than 150 districts adopted a four-day week in the years leading up to the pandemic, one long-running study found that students missed out on 3–4 hours of teaching each week, even with the remaining days of instruction lengthened. Math and English scores fell in those classrooms (particularly among middle schoolers, whose sleep schedules could be disrupted by the earlier start times on days when classes were in session).

A study published last summer echoed those results, revealing significant declines in standardized test scores in six states where large numbers of districts adopted a four-day week. Another paper, focusing on Oklahoma, found no detectable impact on student achievement — though it observed that school expenditures did fall slightly in four-day districts.

It doesn't save a lot of money, it doesn't seem to do good things for students, and we don't have evidence showing that it improves student attendance.

Emily Morton, NWEA

Notably, the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education released state data indicating that implementation of four-day weeks was associated with only minor drops in test performance during the 2019–20 school year, though they disappeared in later years.

Negative findings do not appear to have dimmed the public’s enthusiasm for the idea. In 2023, a poll from the education advocacy group EdChoice showed that 60 percent of parents supported the possibility of their children’s school moving to a four-day schedule; just 27 percent of respondents were opposed.

Emily Morton, a researcher at the assessment group NWEA who has conducted several studies of the effects of the four-day week, said the Missouri paper was yet more evidence that the policy, whatever its attractiveness to parents and schools, did not offer much measurable upside.

“Whether or not the four-day week is a good thing, it doesn’t seem to meet this particular need,” Morton said. “It doesn’t save a lot of money, it doesn’t seem to do good things for students, and we don’t have evidence showing that it improves student attendance. My sense, after studying this for a few years, is that communities just really like it.”

‘This should make everyone very cautious’

Still, with the continuing spread of shortened weeks, more and more states and districts will have to at least give careful thought to their possible impact.

Jon Turner is a former district superintendent in Missouri and a professor at Missouri State University. While not an avowed advocate of the four-day schedule, he has traveled to multiple states to advise school districts considering making a switch. Lately his peregrinations have brought him to Indiana and Pennsylvania, where — as in most states east of the Mississippi River — the practice is still comparatively rare.

No school district makes this decision lightly, and no one sees the four-day week as a solution.

Jon Turner, Missouri State University

Turner said that local K–12 leaders he had met with took the question seriously, often weighing the evidence of achievement losses against their falling student enrollments and challenges in hiring new staff. Many feel the lifestyle flexibility offered by the change is one of the few perks they can offer to teachers who can easily move across district or state lines for better pay.

Particularly in regions where neighboring communities have already shifted from five- to four-day weeks, he added, holdout districts may find themselves at a competitive disadvantage.

“No school district makes this decision lightly, and no one sees the four-day week as a solution,” Turner said. “It’s a symptom of challenges that schools are facing.”

The rapid spread of the trend has nevertheless met some resistance — including in Missouri, where the state legislature recently passed a law requiring larger communities to gain the consent of voters before implementing a shorter school week. In neighboring Arkansas, lawmakers are considering legislation that would establish a minimum school year of 178 days of in-person instruction.

Camp said the results of his study offer forewarning to the education community. In light of the existing evidence around diminished instruction, he concluded, state and local authorities shouldn’t make cavalier decisions with their instructional time.

“This is something that’s a potentially risky gamble, and there don’t seem to be any benefits as far as teacher retention or recruitment. So I do think this should make everyone very cautious about adopting the four-day school week.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)