Jordan: When Racial and Gender Bias Is So Darn Obvious — 2 Studies Offer Suggestions for Real Change

Education research is replete with studies that show how implicit bias can influence the success of students Black and white, male and female. But too often, the evidence of that bias and its impact is muddied by other considerations, such as income, where students live and how their families value education.

Sometimes, though, the bias is so darn obvious that it’s hard to deny. And the results suggest solutions that can lead to real change. Two studies released in the past month, one on race and one on gender, come to mind.

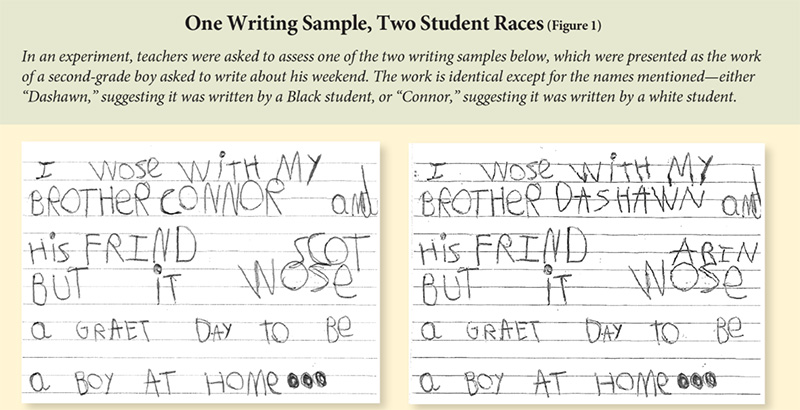

In the first, University of Southern California Assistant Professor David Quinn asked some 1,500 teachers to participate in an experiment on judging student writing and gave each of them a work sample from a hypothetical second-grader.

He used two samples that were identical — right down to misspellings, punctuation errors and sprawling handwriting — except for a key detail. One writer described the day he spent with his brother, Connor, a name associated with white children. The other spent his day with his brother, Dashawn, suggesting a Black author.

Half the teachers were given one letter and half received the other. They were asked to grade it with vague guidance and then with a detailed rubric for judging whether the writing sample was on grade level.

The results: About 35 percent of the teachers who received vague guidance decided that Connor’s brother was on grade level, compared with 30 percent for Dashawn’s brother. The bias was strongest among teachers who are white and who are female — in other words, the bulk of the U.S. teaching force.

Fortunately, Quinn’s research offers its own solution. Among the teachers who received the detailed rubric, there was no significant difference in how the samples were judged. Using such objective measures to assess student work could help combat implicit bias, Quinn argues.

So could diversifying the teaching workforce. Currently, about 79 percent of public school teachers are white, compared with about 48 percent of the students. Research demonstrates that white teachers often have higher expectations for their white students than for their Black students, and that having at least one Black teacher in elementary school can lead to better outcomes for Black students.

The second example comes from higher education, where a University of Florida research team set out to demonstrate gender bias in the ratings that teaching assistants receive from students. The idea was simple: A single assistant in an online class, with no face-to-face contact, gave a man’s name when emailing half the students and a woman’s name to the other half.

When it came time to evaluate the TA who graded their papers and communicated with the class, the female version received five times as many negative evaluations as the male, according to the study, published in November. Female students were toughest on the female assistant: 100 percent of the women assigned to the “male” TA gave a positive rating, compared with 88 percent of women assigned to the “female” version.

These sorts of student evaluations can play a role in whether teaching assistants are rehired for another class — or even whether they choose to pursue a career in teaching. Lead researcher Emily Khazan, a graduate student who also served as the TA in the experiment, said professors have talked to her about negative remarks she received in the past. Plus, the remarks can be “disillusioning,” Khazan said.

The results echo the gender bias found in student evaluations of professors in separate studies by French and American researchers. Those evaluations can influence decisions on tenure and other considerations. Some female professors make it a point not to even look at student comments about their teaching, Khazan said in an interview.

She and her co-authors argue for more research. The bias they found could have been more pronounced, they suggest, because she is a woman in a STEM field, ecology. Or it could have been less pronounced because of the anonymity of the online classroom. Would students have reacted differently if they had seen how their TA dresses or heard her voice?

But research alone won’t turn this around. “You can publish 100,000 papers, and unless you get into a conversation, unless you’re open to talking about this, it’s not going to change,” Khazan said.

Phyllis W. Jordan is editorial director at FutureEd, an independent think tank at the McCourt School of Public Policy at Georgetown University.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)