‘I’ve Never Done Any of This’: Meet the Texas Mom in the Middle of a Political Battle Over Her School District’s Mask Policy

Olivia Weisinger, never a particularly political person, found herself outside the Comal ISD board meeting in Central Texas late last month, rallying parents, students, and teachers to voice their anger over the school board’s decision to eliminate the district’s mask mandate.

“I’ve never done any of this,” Weisinger said in a quiet voice with a tired edge, like a permanent sigh.

Before the pandemic her eldest was happily enrolled in a Comal ISD elementary school, with three younger siblings in line behind him. Now, after a long year at odds with the district over its handling of COVID-19 policies for the district’s 25,000 students, she’s homeschooling her son while filing grievances with the Texas Education Agency, organizing protests, and making videos challenging board members’ statements.

The pandemic, along with the economic and humanitarian crises it has created, have led many people to unlikely places. As they have risen to the occasion — feeding hungry kids, signing neighbors up for vaccines, holding public officials accountable — ordinary citizens have stepped into unofficial public life like never before. Weisinger too has found herself in a new role: activist.

Weisinger and her growing band of parents have battled the board not just about safety but even more about accountability for the seven-member board. To make her point she self-produced a video to fact check claims made by trustee Marty Bartlett during the March 9 board meeting when he voted with the majority to lift the mask mandate.

(Note: The site that published the study mentioned at 0:48 has revised its editorial disclaimer, noting the study has not been peer reviewed, and “should not be interpreted as an endorsement of its validity or suitability for dissemination as established information or for guiding clinical practice.”)

The 74 reached out to multiple members of the Comal ISD school board for comment. None replied.

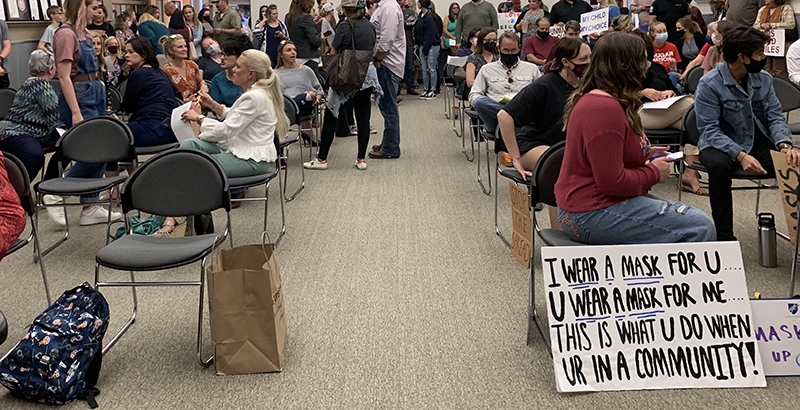

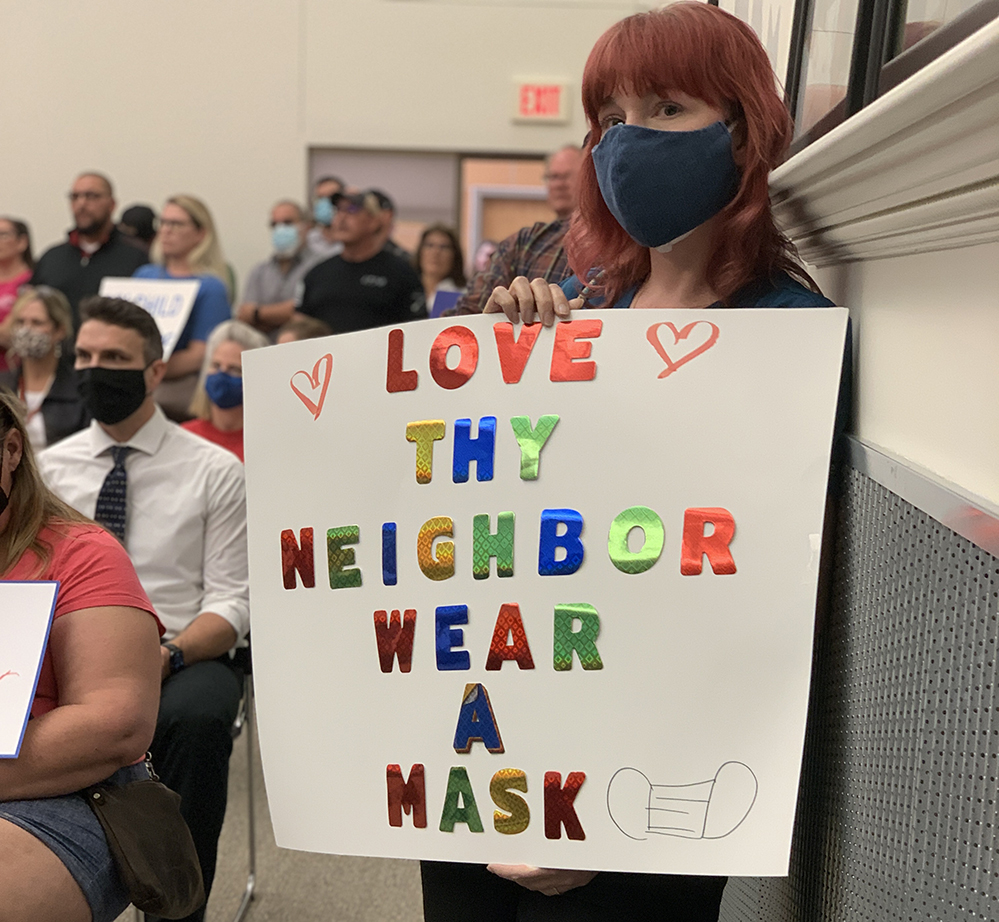

Packed rooms are rare during the pandemic, but the March 25 Comal ISD board meeting was just that. A center aisle divided over one hundred parents, teachers and students who had come to testify on the district’s decision to lift its mask mandate.

On one side of the aisle, masks were scarce. Those parents carried professionally printed signs that read “Kids Need Smiles” and “My Student My Choice.” On the other side, masked parents and students carried homemade signs that said things like “Love Thy Neighbor, Wear A Mask” and “Schools are Supposed to Protect Kids.”

During the pandemic the center aisle has come to represent a seemingly unbridgeable divide between politics and science, and between personal freedom and community responsibility. In Comal County, it now divides those who feel their school district’s governing body is speaking for them, and those who feel they have been betrayed.

Weisinger started a Facebook group, Open Comal County Schools Safely, in August to show the board that parents wanted more caution as schools reopened. She offered to help the district write grants for more air filtration and outdoor classroom spaces. No one was interested, she said. “It was very apparent what you’re seeing now. They weren’t taking COVID seriously.”

As the school year went on, concerns quieted. With a mask mandate and social distancing protocols in place, schools have proved safe. Huge outbreaks have been few, and numbers in most schools remain lower than the general population. In person learning has been a boon to kids who have it, and remote learning has proven to be inadequate and taxing for many children.

Then, on March 2, Gov. Greg Abbott announced that the state’s mask mandate would end a week later, on March 10. The night before the state order lifted, the Comal ISD board voted 5-2 to lift the district’s mandate as well—even though neighboring districts like New Braunfels ISD and Northside ISD, and North East ISD kept theirs in place.

Some parents implored the board to listen to science, while others thanked them for dropping the mandate. Some cited Centers for Disease Control guidelines, others claimed that COVID-19 has been overblown to increase government control. Some referenced a survey conducted by Weisinger’s group. Others questioned the validity of the survey because it was disseminated by a pro-mask Facebook group.

Since the district did not survey parents on the issue, as New Braunfels ISD did, Weisinger’s group decided to conduct their own survey of parents and staff, and found similar results.

The survey went out broadly, Weisinger said, with paper copies and QR codes delivered to families without reliable internet access. Of the 724 respondents, 82% wanted to see the mask mandate continue. Support for a mask mandate was highest in the city of New Braunfels and lowest in the rural areas of the county.

Some of the respondents to Weisinger’s survey shared beliefs that masks are both dangerous and tools of government control, she said. But the numbers were small.

“This division here is a much smaller faction than it feels like,” she said.

That may be true, but they have the board on their side.

Weisinger’s survey showed the majority was with her, but that doesn’t translate to an angry mob.

On the whole, Comal ISD parent Susan Ostrand said, “people just aren’t that upset about it.”

Open Comal County Schools Safely organized a stay-home protest, encouraging families to keep their students home on April 6, the day 4th and 7th graders take state standardized tests. Participation was small.

It was indicative of another sentiment in the district: many would prefer to keep the mask. But fewer are bothered enough to challenge their friends, neighbors, and teachers who are not wearing masks.

Even parents who were ambivalent about masks say that the board could have done a better job considering the needs and perspectives of parents when they lifted the mandate.

Those who did not want to send their children to school with unmasked classmates had about 12 hours to figure out a plan, said Comal ISD parent Chrissy Dyer. She’s okay with the new policy, she said, but knows some working parents were scrambling. “It just wasn’t fair, to me, to do that to those parents.”

That disregard is felt by many, Weisinger said, and is why the resistance mounted by her group isn’t going away. Parents expressing frustration over how the board has handled their concerns involving racist incidents, special education services, and remote learning for bilingual students, reached out to The 74.

People of color felt their concerns were minimized after Drastata called the COVID-19, the “China virus,” which sparked conversation about how racist slurs between students had also been written off as “profanity.” In the district’s push to reopen schools, special education and bilingual services has been substandard, parents said.

Some of these concerns have come through to Weisinger as well, and she’s helping the families figure out what legal recourse they have with the Texas Education Agency. Figuring out how and where to file complaints and grievances has taken up a lot of time, and she had a hard time finding a lawyer familiar with the Texas Education Code.

She’s committed to continuing, though, because there doesn’t seem to be another way for parents in Comal County to have their concerns taken seriously, those related to the pandemic, and beyond.

“This is so much deeper,” Weisinger said, “than COVID and masks.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)