Is Public Education Actually Public? And How Important Is It for Democracy?

Aldeman: Not really, and the link is tenuous at best. Evidence suggests the best path forward is to simply support good schools, regardless of sector.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Is public education the foundation of American democracy, as NEA President Becky Pringle tweeted earlier this spring?

Well, no, not literally. The American experiment that started in 1776 long predated any sort of public education. It’s true that Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence, wrote some nice words about the value of education, but his vision was far more limited than what we might think of as public education today.

The reality is that “public” education wasn’t open to all Americans for much of the nation’s history. Black students didn’t have a right to attend the same schools as white students until the Brown v. Board decision in 1954. Students with disabilities were not guaranteed a free, appropriate public education until the 1973 Rehabilitation Act.

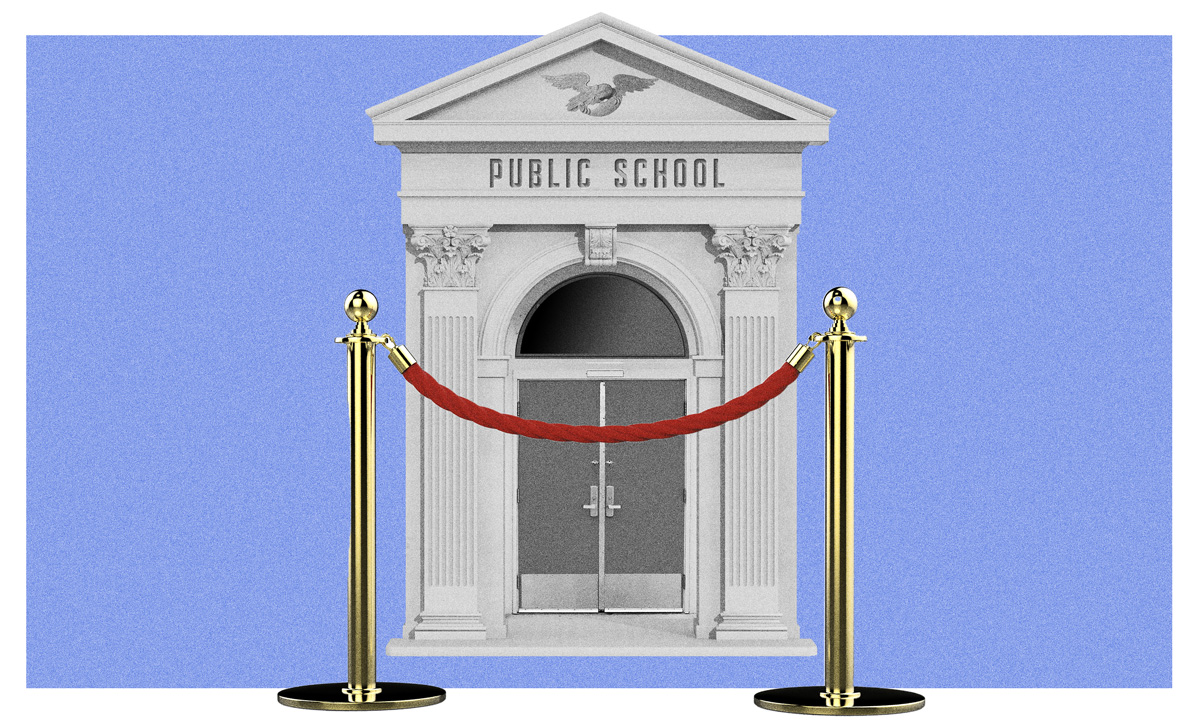

Hard-won lawsuits and pieces of legislation have made schools open to more kids, but they’re still not public in the same way a public park or an FM radio station is free and open to all.

That’s because education has space constraints. There are only so many seats at a school, so local districts reserve spots only for those people who can afford to live in the surrounding community.

I’ll use my own family as an example. We live in Fairfax, Virginia, one of the wealthiest counties in America. There are six “public” high schools within a 15-minute drive of our house, but my kids are zoned for only one of them. We can’t just pick whichever school is the best fit for each child. Our district has a school assignment map that looks as badly gerrymandered as many congressional districts.

Families who can’t afford to buy access to a seat at their preferred public school have to resort to other options. About 12% of students are lucky enough to have magnet or charter schools to choose from, but many do not — and the consequences can be severe.

Here at The 74, Marianna McMurdock told the story earlier this spring of parents who have gone to prison for lying about their address in order to send their children to better schools. Similarly, an investigative analysis from Houston Landing found that Texas districts illegally suspended thousands of homeless students from their schools.

America’s current conception of “public” education says your children are legally entitled to attend any public school they want to … as long as you can afford to live in that community.

Advocates like Pringle have tried to connect public education — such as it is — with the broader project of preserving democracy. In a speech last year, Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona went further, saying, “We need public education to keep democracy alive!”

But the link between public education and democracy is tenuous at best. First, it’s not even the case that higher levels of education automatically lead to increased electoral participation. As one simple illustration, the highest-turnout election was in 1960, a time when less than half of all American adults had a high school diploma.

Second, while it is true that well-educated people tend to be good citizens and are more likely to turn out to vote than those with less schooling, it’s also true that the most highly informed citizens are also the most actively partisan.

Third, cheerleading for the current education system is probably not the best way to strengthen democracy. For example, a recent study found that private school students actually had more political tolerance, political participation, civic knowledge and skills, volunteerism and social capital than those in public school. Charter schools that do a particularly good job boosting noncognitive skills also seem to raise voter participation rates more than other schools do.

In other words, the best way for education to boost American democracy may be for policymakers to support good schools, regardless of sector.

What could that look like? A first step would be to expand public school choice. State leaders could broaden open enrollment to give more students access to more schools. At the local level, districts could expand magnet schools, Montessori or other theme-based schools, public charter schools, early college high schools or dual-enrollment programs.

A more expansive step would be to provide money for families to find their own schools. Last year, I outlined five key guidelines for policymakers to consider in designing those programs, including whether there was a real check on quality and that supports were in place to help low-income families access good schools.

Johns Hopkins professor Ashley Berner-Rogers has been making a similar case for educational pluralism. She notes that many parts of the developed world have public education systems that provide funding to a wider variety of schools. The difference is that those countries — which have their own versions of representative democracies — set standards and accountability rules in order for public funds to flow into different types of private schools.

That’s a form of public education too, albeit a different and more open version than the one most Americans are accustomed to.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)