‘Inundated With Applications’: No Teacher Shortage at Virtual Schools

While many brick-and-mortar districts desperately seek to fill vacancies, online schools often are attracting more candidates than they can hire

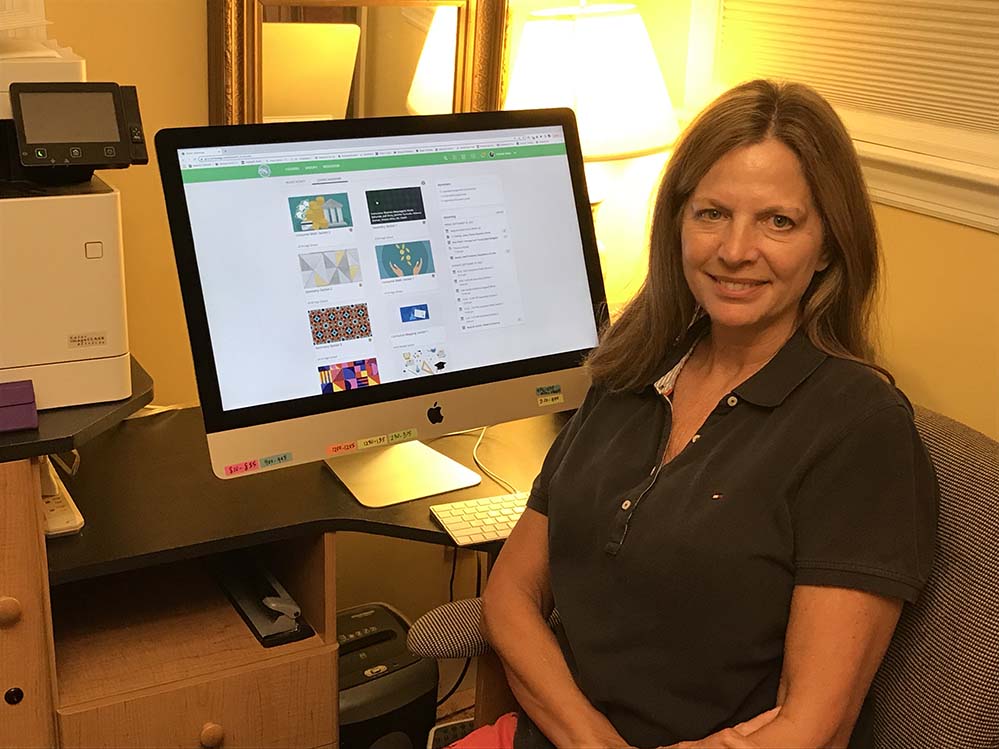

By Asher Lehrer-Small | September 27, 2022Teaching during fall 2020 was so unbearable for Georgia educator Nikki Colwell, she nearly said goodbye to the profession. Her school had returned to campus after a brief pivot to virtual instruction the previous spring, and her job had quickly become more difficult than ever before in her seven-year career.

“I was teaching students in person and online at the same time, dealing with students who were quarantined, trying to maintain social distance in a very small classroom with 20-plus students,” she said. “I gave some serious thought to leaving teaching altogether, even though I didn’t necessarily want to leave the classroom. I just knew that I couldn’t keep doing what I was doing.”

That’s when she found Georgia Cyber Academy, an all-remote school that enrolled students statewide. Her short stint teaching virtually when the pandemic first struck had “played to my strengths as a teacher,” she recalled, so she applied for a position in the English department. By the next school year, the educator had a new job.

On the heels of the pandemic and with reports of stress and burnout reaching all-time highs among the nation’s teaching corps, many — like Colwell — have chosen to migrate online. As a result, while multiple brick-and-mortar districts across the country are desperately seeking to fill vacant teaching positions, online schools say they are often attracting far more candidates than they can hire.

“Anytime there’s an open position, [our human resource officers] are inundated with applications,” said John Johnson, a teacher and former member of the school leadership team at Cobb Online Learning Academy, another virtual school in Georgia.

Throughout the 2021-22 school year, his school had to hire roughly two dozen staff due to steep upticks in enrollment and students nationwide are continuing to leave traditional public schools. “The moment they started posting the positions, they were just having applications coming in left and right” with over 10 candidates per role, he explained.

Halfway across the country, Colorado Connections Academy experienced something similar. The school had an “absolute explosion” in student sign-ups through the pandemic, Executive Director Shannon Cox said, meaning they also had to bring on more staff. Recruitment was easy: “We’ve got more applicants than we know what to do with.” For a recent posting, the school had four candidates within a matter of hours.

“Even heading into this year where all of the local schools are having a very hard time finding candidates, we’re still finding excellent candidates and having a lot of applications,” the school leader said. “So many educators [are] looking for an opportunity to work fully remote.”

Though research shows teacher shortages this year have been concentrated in certain states and regions rather than being rampant across the country, many districts, including Denver, reported hundreds of unfilled positions. Roles like special educators have been especially difficult to fill, a problem that predates the pandemic.

But several virtual school administrators said their institutions have been largely immune to the problem.

An extreme example comes at Lowcountry Connections Academy, an online school in South Carolina. Before school started this fall, the cyber academy posted four new teacher openings. They received roughly 1,050 applications for the roles, said head of school GeRita Connor.

“This is year 20 for me (in education), year 10 as a leader. That’s the most applications I’ve received in my life,” she said.

Much of the interest in the Lowcountry Connections Academy roles came from educators currently teaching at in-person schools who liked the idea of working from home, Connor said.

No longer a ‘non-starter’

No real-time national data tracks how many educators have so far switched from brick-and-mortar to remote jobs, experts say. But there’s been a noticeable change in attitude around remote education since the pandemic, said Colin Sharkey, executive director of the Association of American Educators, which serves over 30,000 school staff nationwide.

“Prior to the pandemic … there was certainly a reticence on the part of a lot of folks in traditional education that [online education] was not going to work. Basically, that was a non-starter,” he said.

But when COVID gave practically all teachers nationwide exposure to the model, Sharkey said, “some got a taste for it and thought, ‘Wow, this actually really accommodates my professional and personal goals better than returning to the classroom.’”

Research from the U.S. Government Accountability Office using pre-pandemic data shows students at online schools score far worse on academic tests than their peers learning in-person, even when controlling for factors like race, poverty level and disability status.

Heather Schwartz, a researcher at the Rand Corporation who has studied virtual schools during the pandemic, has trepidation about the continued trend toward more families and teachers engaging in online education.

“Until we have proof the virtual schools can perform just as well — for at least some students — as traditional public schools, yeah, I’m concerned,” she said.

No lunch duty, no hallway duty

For Colwell, teaching at an online school has meant increased family time and more mobility. Last year, she enrolled her three children in Georgia Cyber Academy, where she was working, and took the opportunity to travel as a family. Over the course of the school year, the group spent time in Egypt and 19 different U.S. states. They planned their transit on weekend days so they could get set up for online school by Monday.

“As long as we were in a location where we had strong internet service, then we could still have regular school and work days wherever we were,” she explained.

Others who pivoted to fully remote teaching jobs since the pandemic echoed that flexibility and work-life balance have been major benefits. They also reported they feel able to serve students in a new and more fulfilling way online.

“When the pandemic hit in March of 2020 … some of [my kids who] did next to nothing in the brick and mortar, when we did the virtual, they just began to be engaged and come alive,” said Victoria Miles, now a math and science teacher at the Greater Commonwealth Virtual School in Massachusetts.

“It just opened my eyes that there’s a real need for this kind of teaching,” she said. Her current students include those with disabilities and hearing impairments as well as professional actors and even a motocross athlete.

After teaching in traditional schools for over a quarter century, Miles estimates the move cost her roughly a 20% salary reduction, but “with that cut in pay, comes a great quality of life increase.”

Johnson agreed. His schedule now includes time to plan lessons and complete his grading, meaning he never has to work longer than eight hours per day. The less enjoyable aspects of the profession, he said, disappear online.

“We never have carpool duty, we never have lunch duty, we don’t have hallway duty, we don’t have to do any of those little things because there are no students on our campus.”

On a similar though darker note, Miles said a significant factor for her in moving to online school was no longer having to undergo active shooter drills.

‘Not for everybody’

The choice among some educators to pivot online is in step with workers across all industries who made career changes or quit outright — part of what some have called the pandemic’s “great resignation,” Sharkey said.

“Teachers are no different than the rest of the professionals who are reevaluating what is important to them. Flexibility, time on task versus commuting … certainly could be playing a big role in why some educators are pursuing full-time virtual careers.”

Educators who recently left the profession and took jobs in other industries cited increased control over their schedule and the ability to work from home as the key draws to their new gigs, a December 2021 Rand survey found. The majority accepted positions with equal or lesser pay, but had less job-related stress.

“Plummeting morale, I think, is pushing some public school teachers out of their in-person teaching,” said Schwartz, a study co-author.

Last year, a former colleague of Miles’s who was still teaching in a brick-and-mortar school called her crying, explaining that she was having difficulty dealing with a student’s behavior. Coincidentally, Greater Commonwealth Virtual Academy had an opening that met the educator’s skill set and soon she joined her friend at the online school. But the change didn’t stick.

“She really missed the interaction, she missed the face-to-face, she missed just having all those kids in a room,” Miles said.

Now, her colleague has returned to in-person teaching. Miles, for her part, has stayed online. Many of her lessons are asynchronous, meaning while some students are watching her teach a lesson online, she’s free to give one-on-one attention to another virtual student who needs extra help. She also appreciates no longer needing to wake up at 5:30 a.m.

But, she acknowledged, “it’s not for everybody.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter