Teaching the ‘Roomers’ and the ‘Zoomers:’ No Small Task for Elementary School Teachers

San Antonio teacher Celina Quintanilla has names for the two groups of 5th-graders she is simultaneously teaching — those in her classroom are the “roomers” and those on Zoom are the “zoomers.”

It’s an arrangement that has sparked resistance from teacher’s unions across the country as teachers say they feel stretched too thin to be effective.

Quintanilla and her co-teacher Daniel Martinez said they feel that strain, but they are doing their best to keep the kids on track anyway. Things are getting better, Martinez said. “In the first couple weeks they were tanking. It was really bad.”

The entire class started remotely in August, and slowly the school has brought back those whose parents agreed to send them. The first invitations went out to children with special needs, no internet connection, or economic hardships that made learning difficult. Teachers also reached out to students who simply were not engaging over Zoom.

“There was a student who I hadn’t even heard her voice until she got here in week eight,” Quintanilla said. She had never seen her smile. At school, even through masks, she said, the student has opened up more.

Those are the students who drew Quintanilla into teaching. “The louder students who speak up more, you can see that they are struggling.” But her heart goes out to the kids like her who are shier, who don’t speak up. That’s the kind of kid she was, as she struggled with a learning disability.

She wants to reach the kids who struggle the most, so she specifically sought out the special education integration class she team-teaches with Martinez.

Usually their classrooms would be decked in vibrant posters and charts and visual aids. Now they are in separate rooms, which are nearly bare to make deep cleaning more effective. The kids are not allowed to get close to one another. Usually the room would have tables instead of individual desks, and the plexiglass shield at her desk also makes the environment feel strange.

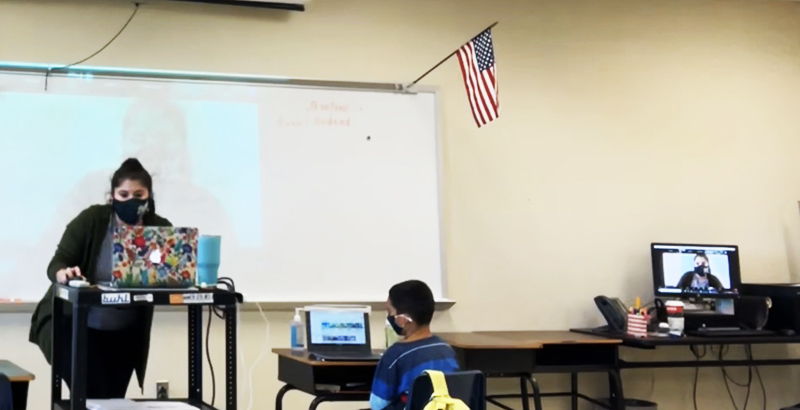

Watching her lead the integrated group of zoomers and roomers, the other challenges of pandemic schooling are clear from the moment Quintanilla takes attendance.

“Turn on your camera, friend,” Quintanilla said, dozens of times in one 35-minute lesson on long and short “O” sounds. Her computer is hooked up to a projector so that the lesson is cast onto the white board. To the side, another monitor is showing the same screen. At the top of each screen are the zoomers: a dozen little boxes filled with faces, some of which she has never seen in person.

Sometimes she sees blank stares on the zoomers, and is at a loss. A few of them, she knows, have never fully engaged with the lessons.

“I don’t know how to reach them,” Quintanilla said. All she can do is keep trying. “I talk to the parents, I talk to them individually.”

After giving some instructions to the whole class, she walked among the 12 roomers, helping with their iPads. She also manages all the things that usually come up in class, in addition to academics.

She’s not just their teacher — she is the adult in charge of the roomers. In addition to the ordinary needs that come up throughout the day — bathroom breaks, water bottle refills, and sleepiness, for instance — teachers have to watch their in-person students for symptoms of COVID-19. Runny noses and coughing might have once been a routine part of the winter classroom, but not during the pandemic.

The students know that between Zoom calls is the best time to go to the restroom or grab a drink, Quintanilla said. While most of the zoomers will let her know in the chat box that they need to step away, it’s more difficult to regulate.

“There have been times when I am calling the students name, get no answer, and the parent will unmute and say, ‘sorry so-and-so went to the restroom,’” Quintanilla said.

It would be all too easy to remain entirely sedentary, locked into a screen all day. Quintanilla and Martinez offer “brain breaks” to allow students to move around, using dance or movement videos they supply. Roomers get 20 minutes of recess, and zoomers get an hour for lunch and free time, and they encourage them to use it to get outside.

Last year Quintanilla and Martinez got rid of their own desks. They spent their days moving around their classes, breaking kids into groups, setting up learning stations, and taking turns working with kids who needed more time. They rarely stood still, making sure each kid was getting what they needed.

This year there’s less movement, as zoomers are tethered to the screens, and roomers must stay six feet apart.

Obviously, this all means the social component of school has changed for students and teachers alike, and it has been another challenge. “I’m very social, and I need people physically here,” Martinez said.

He and Quintanilla move the kids around through breakout rooms, and sometimes the teachers will simply hand over the hosting function on Zoom to switch from one teacher to the other. Small groups of roomers will switch from one classroom to the other.

Weirdest of all, Quintanilla said, is the lack of movement within the classroom.

“Usually I have my students very self-sufficient,” Quintanilla said. “This year I feel like I am doing a lot of things for them, opening the door, sharpening their pencils, turning on and off the lights, trying to minimize the touching of items.”

In the middle of the class she looked at the screen and saw a student using his mom’s phone to zoom in from the car. The student is a zoomer, but he had come to school for an in-person assessment. His mom had allowed him to use the phone in the car so that he didn’t miss anything.

Usually, Quintanilla said, she encourages kids being shuttled to and fro to do just that. But once the class transitioned to independent work, she told the car-zoomer to log off.

“Why don’t you just wait to log in when you get home, friend,” she said.

The team has figured out some of the quirks of remote learning: for instance, in math Quintanilla has to be extra explicit about getting kids to show their work, because the online programs don’t always provide a space for that like written worksheets.

She has them hold up the physical paper they are using to work out the math problems, and show her over zoom. It’s hard to see, with them trying to hold the paper steady and the pixelation on the camera. But, she said, it’s better than nothing.

They are going to keep improving, Martinez said. They have to.

He started teaching 10 years ago after serving with Americorp in a Title I school in Chicago. He still remembers the 3rd grade teacher, Ms. Wilson, who recommended him for a magnet school on the South Side of Chicago, and, he said, changed his life. “I put all my effort into my students because I remember….the effort my teacher put into me.”

That’s why, despite numerous conditions that are less than ideal, he said, he and Quintanilla are committed to making it work. “The passion is still there.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)