Intentionally Diverse Charter Schools: Rhode Island’s Blackstone Valley Prep Spans Race and Class, With a Strong College Focus

Over the past year, researchers from The Century Foundation have analyzed roughly 5,700 charter schools in all 50 states in an attempt to produce the first-ever nationwide inventory of diversity in the public charter school sector. In partnership with the foundation, The 74 released the findings of that report — and today, we are publishing the second of four in-depth profiles of intentionally diverse charter schools, showcasing strategies, policies, and practices that can be replicated and modified by schools elsewhere as they look to pursue diversity as a goal. You can read the first profile here. This school profile was adapted from The Century Foundation report “Blackstone Valley Prep: Intentionally Diverse Network with Strong College Prep Focus.”

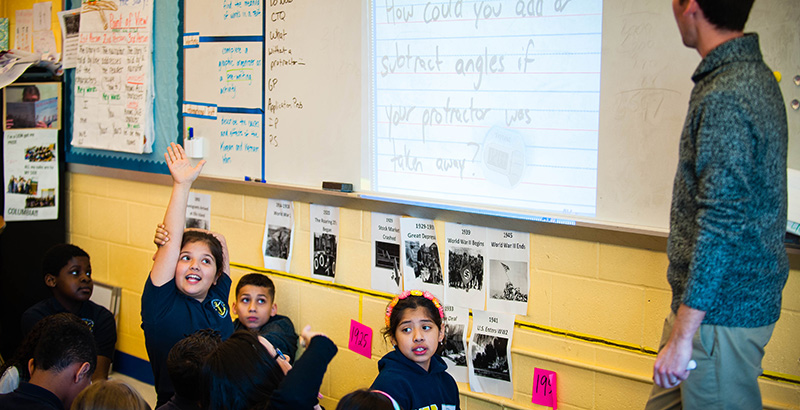

Blackstone Valley Prep, a K-12 charter school network, admits students from across four racially and socioeconomically diverse communities in the northeast corner of Rhode Island. The network integrates students within classrooms, regardless of performance level. Its culturally responsive curriculum aims to reflect and incorporate the range of experiences and backgrounds of its students. The network prides itself on being among the state’s highest performers when it comes to standardized test scores, and its low-income students outperform their peers from the four Blackstone Valley communities.

Its three schools keep a laser focus on college as the goal, from kindergarten through senior year; every classroom is named after a different university. Unlike most other high-performing charter networks, Blackstone Valley has an added dimension of being diverse by design: Students from disparate backgrounds learn with and from one another in classes that are not tracked. All wear uniforms — which can be donated, discounted, and aligned to a student’s gender identity — as an equalizing strategy.

Through the network’s culturally responsive curriculum, students are exposed to texts representing a variety of viewpoints and are encouraged to discuss people’s differences. Through professional development, teachers are taught to become aware of their own biases and structural inequities and to elevate students’ voices over their own. “Our intentional diversity is our greatest asset,” says founding principal Jeremy Chiappetta, who is now the network’s executive director. “It’s our greatest opportunity. It’s our greatest challenge.”

Enrolling a Diverse Student Body

Blackstone Valley Prep’s model was created with integration in mind. Though the network’s boundaries span only an area of about 10 miles by 4 miles, its four communities — Lincoln, Cumberland, Central Falls, and Pawtucket — are economically stratified. Central Falls, for instance, is predominantly Hispanic and low-income; residents’ median household income is $28,900, and the median home value is $164,000. Lincoln, on the other hand, is predominantly white; its median household income is $65,600, and the median home value is roughly $304,000.

Chiappetta was, at first, wary about working with more affluent, suburban students after spending his educational career focused solely on low-income students in high-poverty areas in New York City and Providence. But a mentor, who was a superintendent in Central Falls, convinced him of the importance of integrated schools.

“She says, ‘The most powerful thing you can do for my kids in Central Falls is put them in a seat next to a kid from Cumberland and Lincoln, and the most powerful thing you can do for a kid in Lincoln or Cumberland is to put them in a seat next to a kid from Central Falls,’ ” Chiappetta recounts.

Diversity in Recruitment and Enrollment

The network’s enrollment lottery is designed to ensure both that its four sending districts are represented proportionally — ensuring racial diversity — and that a significant portion of students come from lower-income families. Half the students across the network are Latino, 36 percent are white, and 11 percent are black. Blackstone Valley aims to give at least 50 percent of available seats to students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch (the network presently exceeds that, with nearly 68 percent of the network’s students qualifying). Though the student body has increasingly tilted low-income, school officials have not discussed weighting the application process to favor middle-class students, according to Vanessa Douyon, the network’s director of strategy.

“Never say never, but I don’t see this in our future, as of now,” says Douyon. “Given the state of our education system — where student opportunities and performance correlate highly with income — I think that many of our teachers and staff are particularly motivated to ensure that kids who may not otherwise have access to a great education are served at BVP.”

The model, however, is predicated on having a mix of students with a range of needs. Guidance counselors and other support staff can often offer more assistance to those with higher needs when they are not exclusively serving high-needs students, says Jonathon Acosta, a former middle school math teacher and dean of culture at Blackstone Valley who now serves on the Central Falls city council and is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at Brown University.

Blackstone Valley received more than 2,010 applications for 292 seats in the 2017–18 school year.

When it comes to recruitment, the network tries to inform families of all backgrounds about the schools. At the same time, having too many people apply would dramatically decrease the likelihood of selection, explains Douyon. The network ensures that its website is updated, sends out reminders and announcements through social media, hosts several elementary and high school open houses, takes out ads in local newspapers, and provides current families with information cards to give to relatives and friends.

Co-teaching and Differentiation

To support differentiation within the classroom, most of the network’s K-8 classrooms are co-taught by a pair of teachers (either a special education teacher and general education teacher or two general education teachers). The schools employ different co-teaching models, including parallel teaching, “station” teaching, or having one lead teacher with an assistant.

Second-grade teacher Kourtny DaRocha says she and her co-teacher “divide and conquer,” with DaRocha working with the struggling students, including those with disabilities or who are English learners. Her co-teacher focuses more on the higher-achieving students. They divvy up those falling in the middle.

“By doing that, we are able to reach them and work with them in a pretty individualized way,” DaRocha says. “You can’t make 28 different lessons for 28 different kids. We plan for the strongest 5 percent and from there scaffold down.”

Focus on Personalized Learning

With a grant from Next Generation Learning Challenges — funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation — the high school uses a blended learning model. Students spend much of their classroom time in group discussions and on project-based learning, while outside class they have access to online lectures and content using ChromeBooks that the school gives to each student.

The network partnered with California’s Summit Public Schools on a personalized learning platform created with the help of developers from Facebook. The platform allows students to chart their progress on coursework and enables teachers to see where students are getting stuck or having success. Many education experts hope that giving more students autonomy and tailoring the curriculum to their individual needs in this way could help narrow the achievement gap.

Cesar Urzua, a junior from Central Falls, believes the program is helping him learn the time management skills he’ll need for college. Unlike his friends who go to district schools, where homework assignments consist of specific pages to be read and questions answered by the next day, he and his classmates are given assignments at the beginning of the semester, as in a college course, with due dates sometimes weeks away.

Culturally Responsive Curriculum

For teachers, the network’s professional development addresses bias, stereotypes, and the history of structural racism in the United States, and its rubric for evaluating educators, administrators, and support staff includes cultural competencies. Chief Academic Officer Sarah Anderson explains that while these issues are hard to measure, the presence of cultural competencies on its rubric allows the network to have conversations with staff about issues like race and class.

Blackstone Valley is also focusing on these issues in the curriculum itself — and on how teachers are interpreting it to make their teaching culturally responsive. Part of that comes from giving more voice to students, who now, for instance, lead their own parent-teacher conferences.

For example, the humanities curriculum includes books from diverse authors. Kindergartners learn to celebrate differences with such titles as I Like Myself and Nappy Hair. First-graders read Squanto’s Journey, which tells the story of the first Thanksgiving from a Native American perspective. Second-graders read Cinderella stories from around the world. The school also tries to guide how students use their nonacademic time by providing prompts to get kids talking and thinking about diversity.

Conclusion

As an intentionally diverse network, Blackstone Valley Prep not only enrolls a racially and socioeconomically diverse student body by design; it also integrates students within the classroom. The results have been positive for the school’s low-income students, who outperform their peers in the four Rhode Island communities from which the network draws.

In deepening its core mission as a diverse charter network, Blackstone Valley has developed a culturally responsive curriculum and is fostering diversity among staff, but it is still working to meaningfully connect parents from diverse backgrounds. As the network grows, it has rethought some of its strictest policies: shortening the long school day by an hour, reducing the homework load, and moving toward more restorative approaches to discipline. It is also trying to give its schools more autonomy — which leaders hope will help with teacher retention — while remaining true to its unifying vision as a high-performing, integrated charter network.

Amy Zimmer is an award-winning journalist based in New York.

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to The Century Foundation’s project on charter school diversity and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)