Intentionally Diverse Charter Schools: In New Orleans’s Morris Jeff Community School, Elevating Inclusion and Teacher Voice

Over the past year, researchers from The Century Foundation have analyzed roughly 5,700 charter schools in all 50 states in an attempt to produce the first-ever nationwide inventory of diversity in the public charter school sector. In partnership with the foundation, The 74 released the findings of that report — and today, we are publishing the first of four in-depth profiles of intentionally diverse charter schools, showcasing strategies, policies, and practices that can be replicated and modified by schools elsewhere as they look to pursue diversity as a goal. This school profile was adapted from The Century Foundation report “Morris Jeff Community School: Elevating Diversity and Teacher Voice.”

In a city where the educational landscape is dominated by charter schools, Morris Jeff Community School stands out. Eight years since its founding, the charter school has become known for its International Baccalaureate curriculum, dedication to ability inclusion and diversity, commitment to teacher voice, and academic consistency. The New Orleans school articulated these principles at its founding, committing to being an institution that not only serves the surrounding community but also involves and reflects it.

Morris Jeff Community School opened in fall 2010 after two years of persistent pressure by a coalition of parents, educators, and community leaders in the Mid-City and St. John neighborhoods. Originally, their goal had been to save Morris F.X. Jeff Elementary School, a high-poverty, well-respected, local district school that primarily served African-American students. But like most of the city’s public schools, Morris F.X. Jeff was closed in 2005 after Hurricane Katrina, and when the state-run Recovery School District took control of the old Morris F.X. Jeff building, it decided not to reopen the school.

By March 2007, cleanup contractors were emptying the still-vacant building and discarding everything inside, including books and school supplies, classifying them as “storm debris.” But determined to try to reopen the school, concerned citizens decided to organize. Critically, the group, calling itself Neighbors for Morris F.X. Jeff School, reflected the diversity of the Mid-City neighborhood, cutting across lines of race, class, and generation. And as the group grew in number, it settled on its ultimate goal — to create a community school as racially and economically diverse as the neighborhoods that surrounded it.

When it became clear that Morris F.X. Jeff School would not be saved at its current site, organizers turned their attention to designing a new school. Forming standing committees to handle finance, fundraising, community outreach, curriculum, and leadership, they decided to form a different type of charter school, one created through community and emphasizing democratic citizenship as well as academic accountability. As a part of that commitment, the school’s board sanctioned a teachers union, a rarity in the charter school world. The board hired its founding principal, Patricia Perkins, and Morris Jeff Community School opened in 2009.

In both its unionized teaching force and its diverse student body, Morris Jeff is swimming against the charter school tide. In fact, one observer called Morris Jeff “an anti-charter charter.” In its first incoming class, in 2010, 55 percent of students were black, 36 percent white, and 9 percent Hispanic, Asian, or other races and ethnicities. Fifty-eight percent were from low-income families.

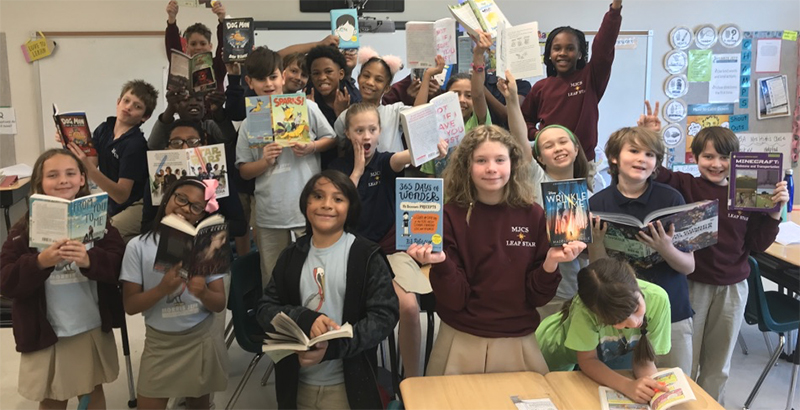

Today, Morris Jeff enrolls students from pre-kindergarten through ninth grade in a large, brightly lit building. Last fall, it served 826 students; just over 58 percent were considered “at risk,” 54 percent were black, 13 percent were Hispanic, 28 percent were white, 4.5 percent were Asian or multiracial, and just over 5 percent had limited English proficiency.

Teachers and administrators emphasize that this demographic diversity, in an otherwise highly segregated city and educational system, is a source of both pride and strength. It is rooted in the school’s pre-K admissions mechanism — Morris Jeff signs up most of its new students in preschool and participates in a statewide program that supports mixed-income enrollment for pre-K. In the upcoming academic year, Morris Jeff plans to enroll 50 students from low-income families for free pre-K and will enroll another 29 from non-eligible families who will pay tuition.

Children with learning disabilities and kids residing in the ZIP codes surrounding the school also get priority. Morris Jeff guarantees all its pre-K students admission to kindergarten — understanding that the pre-K admissions model encourages socioeconomic integration, school leaders work hard to retain those children and move them into higher grades.

But Morris Jeff does not solely rely on its built-in pre-K diversity to ensure that its student body stays representative. Because the school is under the guidelines of New Orleans’s OneApp office, which runs school choice and enrollment in the district’s nearly all-charter system, it cannot use a lottery that is weighted to achieve socioeconomic and racial diversity. In response, it’s gotten creative.

When Morris Jeff first opened, Perkins and organizers pulled out all the stops to spread the word that a new school was coming to the neighborhood. “We had trick-or-treating booths at Halloween where we gave out Morris Jeff flyers. We participated in a Mardi Gras parade on one of the biggest parade days,” she says. “We went into churches in the community and spoke. We held meetings at coffee shops; [we did] anything and everything that we could do to get the word out.”

According to Perkins, about 35 percent of Morris Jeff students live in the surrounding neighborhood. The city or district will not pay for transportation for non-neighborhood students, forcing Morris Jeff to pay out of pocket for buses, a financial burden that is frustrating.

Today, the school’s reputation for nurturing and inclusion does a significant portion of the recruitment work. Each year, the school hosts a massive open house and organizes information nights to acquaint current and potential parents with the culture and curriculum. Before school lottery season, Morris Jeff yard signs pop up in neighborhoods, and commuters hear Morris Jeff radio ads. The school offers parent and family tours every Tuesday throughout the academic year, and it plans informal community get-togethers. Ferria, a large, schoolwide fair hosted every spring, has become a big recruiting event.

Academic Performance

Marketing, community outreach, transportation, and admissions practices all support the school’s ability to attract and retain diverse parents, but its status as the first elementary school in Louisiana to be authorized as an International Baccalaureate World School helps distinguish it from other options. The IB distinction, though not officially authorized until fall 2013, became a part of Morris Jeff’s charter in 2010, when interested parents began to research engaging educational curricula. Now, IB’s “learner profile” — 10 attributes that seek to produce engaged and productive thinkers — is the core of the school. Pasted on walls across the building, the IB attributes are imbued into every part of the student and staff experience and serve as a selling point to potential new families.

In fact, many of the learner profile attributes — caring, principled, knowledgeable, open-minded, inquirer, communicator, reflective, thinker, risk-taker, and balanced — align with outcomes well-documented in research about the benefits of diversity. Evidence shows that integrated classrooms encourage critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity (inquirer, reflective, thinker), reduce bias and counter stereotypes (caring, open-minded), spur a willingness to seek out diverse spaces later in life (principled, balanced), and can improve student satisfaction and leadership skills (communicator).

Morris Jeff’s test scores demonstrate that the school’s academic and cultural approaches are generally successful. Based on the most recently available LEAP scores, which measure “student proficiency of grade-level content and true readiness for the next level of study,” Morris Jeff students performed better than the Orleans Parish/Recovery School District average and the Louisiana state average. Subgroups of students, including economically disadvantaged students, students of color, and students with disabilities, also outperformed their peers across the district and the state.

Despite these successes, however, there remains significant room for improvement: The school earned a C rating from the state during this academic year (however, the school’s overall score, an 80.8, was a full 10 points ahead of the overall score for its host district).

Clearly, simply assembling students of different backgrounds is insufficient; achieving positive outcomes requires an infrastructure not only for racial and socioeconomic diversity but also for equity within a diverse space. From its founding, Morris Jeff has sought to build up this infrastructure, but it remains a work in progress.

Ability Inclusion as a Fundamental Principle

When a visitor walks around Morris Jeff, she will undoubtedly see children of different physical and cognitive ability levels meaningfully interacting with each other. In a fourth-grade class, when a medically fragile child with verbal limitations suddenly shrieks in pain and frustration during a lesson, her classmate quietly approaches, sits next to her, and grabs her hand in comfort. In another class, several students share a laugh with a boy with Down syndrome.

Like its commitment to racial and socioeconomic integration, this high level of inclusion of special needs students is by design. Perkins says the philosophy links back to Morris Jeff’s mission to mold a community across difference. “Why are we still isolating children from our society just because they are different?” she asks. “And what is it about us as a society that we can’t yet fully embrace and accept and share ourselves with others who might learn and look differently — beyond just racially and economically?”

Principal Patricia Perkins on ability inclusion

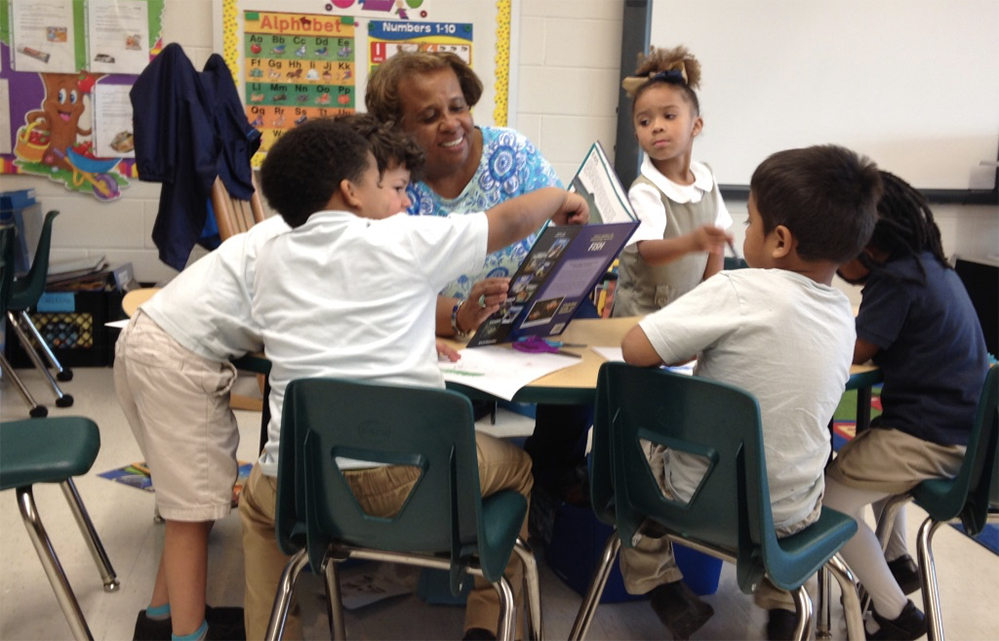

Morris Jeff dedicates a great deal of time and staff resources to ensure that the school serves special needs students well. About 13 percent of Morris Jeff students have special needs; academic results for these students are far above state and district averages. Special education students are not separated into different classrooms at any point, but instead sit next to cognitively typical students in the classroom. Ginger Woodall, a special educator focusing on speech therapy, describes this full inclusion model as the philosophy that “every student is a general education student first.” Each classroom has multiple adults, including student aides or special educators. Throughout the day, when the lead teacher presents the lesson and works with small groups, specialists “push in” to general education classes to help students who require additional learning supports.

Fifth-year teacher Kristen Weddle appreciates the full inclusion model but admits that it’s challenging. The common planning time and amount of intervention, while helpful, “never feels like enough,” she says. But the structure of the classes themselves lends itself to more collaborative teaching experiences and student breakout groups. “My team uses a lot of workshop models and small grouping within classrooms,” Weddle explains, which helps provide times when specialists can discreetly push in without interrupting a lesson.

As a result, the inclusion model seems to have led to positive changes for all students. “We’ve embraced personalized learning for all of our kids,” Perkins says. Newly purchased technology allows teachers to give additional time face-to-face with one group of students, while classmates in the same room can work on a curriculum-unit-aligned program on a tablet or laptop that is more closely tailored to their needs.

Respecting and Honoring Teacher Input

Within the charter sector, Morris Jeff’s level of commitment to elevating teacher voice is rare. Before the school even opened, its founders wanted teachers to have the option to form a union.

In 2013, teachers decided to unionize in an effort to preserve the school’s collaborative character as it continued to expand. The charter’s board formally recognized the union without a formal vote after receiving the faculty petition, making Morris Jeff the first school to unionize in post-Katrina New Orleans. To this day, it is one of only three unionized charters in the city.

After a three-year negotiation, the teachers and governing board ratified a contract in June 2016. The 30-page document provides an uncharacteristic degree of job and salary security in a state where such assurances are tenuous at best. It ensures that teachers employed at Morris Jeff for more than two years cannot be disciplined without just cause, establishes a 90-minute daily planning period, offers help to struggling teachers prior to re-evaluation, and freezes or increases salaries for teachers and teaching assistants.

The contract also establishes policy and governance committees that mandate the inclusion of teachers. The Student Support Committee, for example, consists of four teachers designated by the union, three administrators, the special education director, one board member, and two parents. Provisions approved by this committee become official school policies.

As the school builds out its grade levels and faculty, it also seeks to develop a more diverse teaching and administrative staff. Currently, the teaching force is around 60 percent white, 33 percent black, and 6 percent Hispanic. Ideally, school leaders would like the faculty to more closely reflect the demographics of the student body. They hope to recruit more staff from programs that serve as hubs for young educators of color, such as historically black colleges and universities, Teach for America, and Teach NOLA programs.

Music teacher Steven Kennedy on the Student Support Committee

Conclusion

In its colorful building in the heart of one of America’s most colorful cities, Morris Jeff strives to remain a community-based, diverse, and effective school — while still growing in size and scope and tackling tough barriers to full equity. Although imperfect, the school has reasonable but ambitious plans to address its blemishes. Its investments in better learning interventions, tutoring programs, data collection tools and training, and anti-racist professional development are promising changes and additions to its model.

At the same time, the school holds fast to the elements that define its character: a community-centered experiment in racial, economic, and ability inclusion; a nurturing educational environment with universal access to music, art, and foreign language; and a commitment to hearing and respecting the voices of educators through its union.

Kimberly Quick is a Century Foundation senior policy associate.

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to The Century Foundation’s project on charter school diversity and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)