Intentionally Diverse Charter Schools: In Denver, Students From Varied Backgrounds Prepare for One Bright Future, Together

Over the past year, researchers from The Century Foundation have analyzed roughly 5,700 charter schools in all 50 states in an attempt to produce the first-ever nationwide inventory of diversity in the public charter school sector. In partnership with the foundation, The 74 released the findings of that report — and today, we are publishing the last of four in-depth profiles of intentionally diverse charter schools, showcasing strategies, policies, and practices that can be replicated and modified by schools elsewhere as they look to pursue diversity as a goal. (You can read the first three profiles in the series here, here, and here.) This school profile was adapted from The Century Foundation report “Protected: Denver School of Science and Technology: Students of All Backgrounds Preparing for One Bright Future.”

The Denver School of Science and Technology network, serving a student body that mostly reflects the racial and socioeconomic enrollment of Denver Public Schools, was established as a single school in 2004, with a vision of intentional diversity and resistance to tracking students into different courses. Today, the highly regarded charter network runs five of the eight best middle schools and four of the five best high schools in Denver. Since its first graduating class 10 years ago, 100 percent of its graduates have been accepted to college.

But DSST, whose generally low-income student population performs consistently well on state standardized tests, prides itself on more than just its results on exams. Its teachers and leaders emphasize that the network’s six core values — respect, responsibility, integrity, courage, curiosity, and doing your best — impact the choices of students and staff alike. From home visits for every high school student in the network to student-fostered peer tutoring, DSST is built on a foundation of balancing challenging academics with a philosophy of caring.

Student Outcomes

DSST schools are some of the most celebrated in the nation. Among the top-performing schools in the state of Colorado, the network is known for its high test results achieved by low-income students and students of color. In fact, DSST students who qualified for free or reduced-price lunch had a higher average SAT score in 2017 than did all Colorado students who did not qualify for federal meals programs.

Most DSST schools far exceed the state’s mean score on the annual Colorado Measures of Academic Success in English, math, and science. Those that do not — DSST Henry Middle, Cole Middle, and College View Middle — approach the state mean and produce scores that demonstrate higher-than-state-average performance for most student subgroups, including English learners, minority students, and those who are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.

Tracking Success, Not Students

To measure student growth and achievement, the network’s schools rely heavily on frequent academic assessments to measure individual student as well as overall classroom performance. Struggling students can be referred to mandatory tutoring.

Because the network does not screen for academic preparedness, DSST students arrive with varied levels of skill. Incoming sixth-graders are required or strongly encouraged to attend DSST summer school prior to the academic year, but this pre-emptive intervention does not close all preparation gaps. Frequent testing, in part, helps teachers and administrators identify performance trends across groups and, in some cases, make determinations about a student’s course placement.

With a goal of maintaining diversity, students are evaluated each trimester and placed into performance bands to help teachers address varying strengths and needs within each classroom. The schools spend several days after finals analyzing the data and determining strategies to assist struggling students and differentiate instruction.

Because of DSST’s emphasis on in-class differentiation and commitment to equity, student tracking is not a major part of its model. Dan Sullivan, director of the middle school at DSST Stapleton, says one key to the network’s success is its insistence on holding all students to very high standards. “We try to set the bar very near the top and really think about all of the scaffolds, rather than setting a lower bar and thinking about challenging the kids who are up,” he explains. To ensure that all students reach those standards, the schools use varied interventions: pullout math or reading enrichment, push-in reading interventions, English language development coordinators for English learners.

Deeper Learning Through Practical Engagement

In keeping with the network’s mandate to produce high-achieving graduates who will go on to serve the Colorado community, DSST high schools require all students to do an internship for one trimester of their junior year, working a minimum of four hours per week for 10 weeks and participating in an accompanying weekly seminar. Internship coordinators help students identify areas of interest and arrange placements for them. Students work in a range of environments, from the Denver Zoo and Colorado University Hospital to Teach for America, engineering and architecture firms, and political campaigns. At the conclusion of their internships, students give presentations to the school community about their experiences.

An optional separate venture, DSST’s Entrepreneurship Program (E-Ship), similarly aims to expose students to real-life applications for what they learn in class. Students can take entrepreneurship courses as electives starting in seventh grade. Currently, about 600 students participate in these courses, which provide the opportunity to pair creativity with business acumen and build confidence as students work in groups to design products or produce projects with Colorado-based startups.

Jeremy Wickenheiser, founder and director of the program, says E-Ship is one way of educating kids for the future. “We are trying to prepare kids for jobs and careers that don’t yet exist. The memorization of content doesn’t matter in the same way anymore. How can you take it and apply it … how can you constantly continue to learn?” he asks.

For students in the upper grades, this might mean receiving assignments with questions that lack known answers. “We might ask students to do a project,” explains Wickenheiser, “where they get on a bus — not knowing where they are going — and they head over to a company … meet with the chief officer and executive team, and hear about their work. And then they [tell the students], ‘We have this problem that we could use some solutions for, and we can’t wait to see you in a couple of weeks to deliver us solutions.’ ” This type of assignment is critical, he argues, because fully preparing students for the real world requires constantly learning and figuring out the unknown.

Conclusion

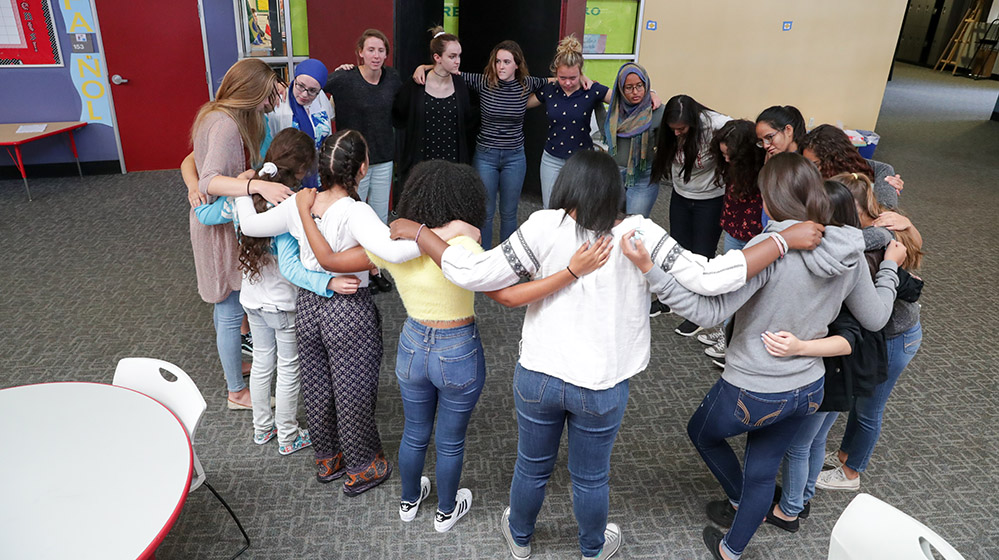

In a sixth-grade social studies class at Green Valley Ranch, a diverse group of students sit in a large circle, discussing race and equal rights. The teacher sits at the side of the class, taking notes and listening intently, but does not lead the conversation. Instead, she watches as the 11- and 12-year-olds reference literature as they grapple with the some of the most divisive questions facing our nation. With no adult intervention, students begin asking one another questions, ensuring that their peers of different backgrounds have all gotten a chance to speak. When a black girl looks like she’s itching to say something, a Hispanic boy invites her to share her ideas.

These types of conversations, held by diverse students in untracked classes, help DSST realize its goal of producing the next generation of active, thoughtful citizens. The network’s identity as a high-performing, intentionally diverse, STEM-focused school is paired with its promise to remain deeply committed to the success of all its students, regardless of background. However, DSST is far from perfect. Its aversion to tracking does not prevent older students from being sorted into different mathematics classes, its special education population struggles to achieve and graduate at acceptable rates, and its strict discipline appears to come down disproportionately on students of color. As it continues to evaluate its data and update its practices in these areas, the network works to build new schools using the tools that it knows are most effective.

Kimberly Quick is a Century Foundation senior policy associate.

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to The Century Foundation’s project on charter school diversity and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)