Inside the Fight to Save Detroit’s Schools: Betsy DeVos’s Campaign for Choice Over Local Control

In 2015, after months of intense internal discussion and debate, the coalition released an ambitious set of recommendations designed to improve Detroit schools, which based on national tests are among the worst in the country and were facing a massive financial crisis, including potential bankruptcy. The group called for additional funding, improved charter authorizer practices, greater school accountability, a more empowered school board and the creation of a commission that would coordinate the placement of new schools.

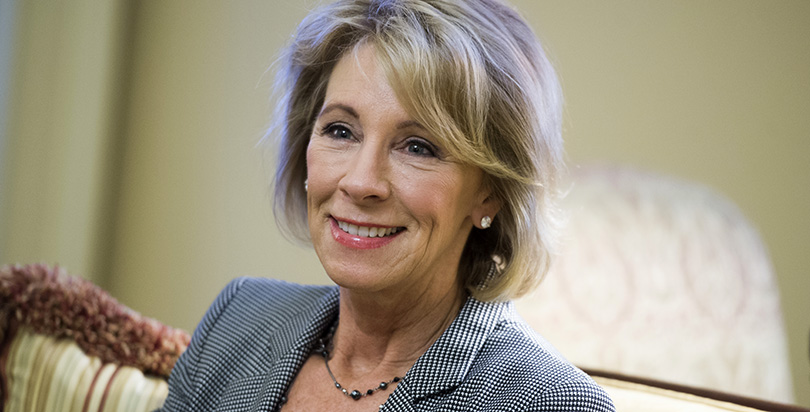

Enter Betsy and Dick DeVos — Grand Rapids billionaires, Republican power brokers and longtime school-choice advocates — as well as groups and politicians they had handsomely funded, who agreed with many of the coalition’s accountability recommendations but were strongly against a commission with potential veto control over new schools.

In the end, key aspects of the coalition’s recommendation, particularly the oversight commission, never made it into the final $617 million rescue bill for Detroit Public Schools — with many education observers and political players saying the DeVoses’ influence was the reason.

“I believe that organizations that I would consider as emissaries for the DeVos family had significant influence and were directly responsible for the failure of the [oversight commission],” said Tonya Allen, co-chair of the coalition and CEO of the Skillman Foundation, an influential Detroit-based philanthropy organization that backed the coalition and whose roughly $17 million in annual grants include many aimed at reshaping public education in Detroit.

The DeVoses and others who formed a separate coalition, based largely outside of Detroit, to defeat the proposed commission said it would have vested too much authority in the city’s mayor, whose housing-demolition program was under federal investigation.

The Detroit Education Commission “would have eliminated local control, and instead placed all schools under the control of the Mayor’s political appointees,” Ed Patru, a spokesman for Friends of Betsy DeVos, said in an email. “It’s well known that the Mayor and his political appointees are beholden to organized labor — a special interest whose singular priority is to shut down charter schools and eliminate choice.”

There was also significant opposition to the education commission among Detroit residents, according to one poll — including from some foes of charter schools — but among Detroit’s elected officials there was virtually no support for the bill that ultimately became law and included controversial additions that appeared to target teacher unions. Not a single Detroit legislator voted for it.

A spokesperson for the Trump transition team declined to make Betsy DeVos available for an interview.

Now that DeVos has been nominated for education secretary, her time in Michigan hints at how she could lead the Department of Education. Given her advocacy in Detroit, DeVos and groups with her backing have shown they will move swiftly to oppose any prior restraint on charter schools — and, in doing so, are willing to override local elected officials and other grassroots forces.

Detroit Public Schools have long faced challenges, including dreadful test scores, financial mismanagement and corruption scandals. Enrollment plummeted as residents fled the city. Many students whose families remained attended public schools in neighboring districts, while others left district schools for Detroit’s swiftly growing charter sector. More than half of the city’s students attend charter schools, the second-highest share of any city in the country, behind only New Orleans.

The Coalition for the Future of Detroit Schoolchildren was formed to try to fix years of dysfunction now being made worse, supporters say, by outside forces.

“A group of leaders in our community acknowledged that our educational system was continuing to decline, and Detroiters had very little say in what was happening,” said Allen, whose foundation has funded organizations that argued that Detroit charters lacked accountability.

“It was a remarkable coalition that formed,” said David Arsen, an education researcher at Michigan State University. “It brought together the people who were at each other’s throats for years.”

The group worked behind the scenes for some time to build support for its proposal, which included a large infusion of money to pay down the district’s debt; the Detroit Education Commission appointed by the mayor, whose members would rate, oversee and even open and close schools, charter and district alike; and unified systems for transportation, enrollment and accountability that included both charters and districts.

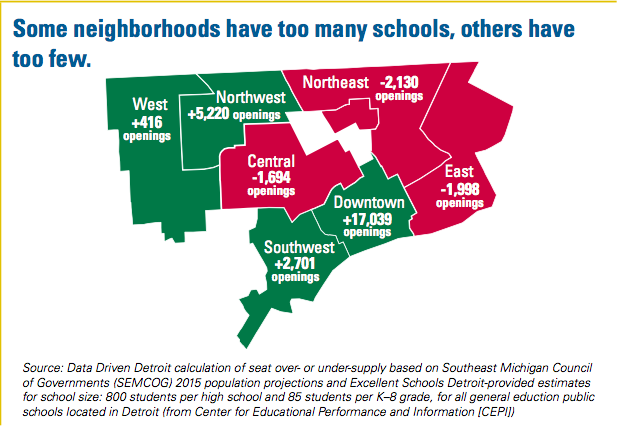

The idea of the oversight committee was to bring greater coordination to a system where in total there were more open school seats than students, but in certain parts of the city, there were not enough.

In many ways it was designed to be a so-called portfolio model, similar to New Orleans and supported by many education-reform organizations. The idea is to allow for significant choice among families and also ensure strict regulations and accountability.

Returning to some semblance of community control was a key goal for coalition members.

“At the time, we had basically a public school system that was run by a governor-appointed state manager; we had charter schools that were being authorized by essentially a state-appointed university board; and then we had a new educational entity that was created by the governor as a low-performing school district,” said Allen.

After extensive backroom discussions, legislation was crafted that included many of the coalition’s recommendations. Those negotiations, according to two sources, included a representative of National Heritage Academies, a for-profit charter chain. The chain is more politically aligned with DeVos — Heritage’s founder, J.C. Huizenga, is also a wealthy political donor from Grand Rapids — than members of the coalition, and, according to sources, National Heritage successfully pushed to ensure that only the lower-ranked charter operators had to seek permission from the commission to expand. A spokesperson for the charter group declined to comment.

Support for the coalition’s recommendations came from a diverse group, including some Detroit Democrats and Senate Republicans, Republican Gov. Rick Snyder and Detroit’s mayor, Democrat Mike Duggan.

In March 2016, the state Senate passed a package of changes that was similar to what the coalition proposed and included the commission. Most Democrats and about half of the Republicans supported the bill.

Betsy DeVos and the state’s powerful charter school lobby had a different idea. They viewed more school choice as a solution to the city’s woeful education performance and Detroit Public Schools as the problem.

“We must acknowledge the simple fact that DPS has failed academically and financially — for decades. We need to retire DPS and provide new and better education options that focus on Detroit schoolchildren,” DeVos said in a February 2016 essay for The Detroit News.

“When school districts are abject failures in terms of their ability to provide kids with a quality education, Betsy believes reform is needed,” said Patru, the Friends of DeVos spokesman. “She rejects the absurd and offensive notion that the goal of education reform ought to be the preservation of bad traditional schools rather than the education of children.”

The group Great Lakes Education Project (GLEP), which was founded and funded by DeVos, started the Twitter hashtag #EndDPS.

“If we had our way, if we were really running the show here, there would not be a DPS,” said Gary Naeyaert, GLEP’s executive director.

DPS' status as the WORST urban school district in the country has been confirmed. #EndDPS #MichEd https://t.co/L2BGA0RlV0

— GLEP (@GLEP_MI) October 28, 2015

DeVos and some charter school advocates said the problem with the oversight commission was that it could be packed with opponents of charter schools who could try to bolster DPS by limiting the creation of new charters and closing down existing ones.

“It is indisputable that one of the stated objectives of the [commission] was the preservation of the education establishment,” said Patru. “Betsy opposed [it] because it would have put all education decisions in the hands of a Mayor who was under federal investigation for fraud and abuse with city contracts.”

Most labor unions — including the AFL-CIO, which the American Federation of Teachers Michigan is affiliated with — did not support Duggan when he successfully ran for mayor in 2013.

Although assessing the impact of charters in Detroit is complicated, supporters cite a study from CREDO, a Stanford University–based research group, showing that students in Detroit charters demonstrate more growth on standardized tests than those in district schools. (See our analysis of the data surrounding Detroit’s charter schools.)

The Coalition Opposed to the Detroit Education Commission, which included GLEP, was formed, arguing that “allocating significant authority to such a political entity is a threat to every parent and student selecting the best school for their learning needs.” The coalition was made up of charter advocacy organizations, free-market think tanks and other groups funded in part by the DeVoses, charter operators, and education businesses and consulting firms. Just one was based in Detroit.

National Heritage Academies, never a fan of the commission to begin with, would also end up pushing for its removal.

In the city, a number of charter school heads backed the commission. In May, 20 charter leaders appeared alongside Mayor Duggan to support its creation, and later that same month, 27 Detroit charter parents wrote in the Detroit Free Press that “the special interests who are trying to scare us by claiming the [commission] will take away our choice are not in touch with our experiences, and certainly do not speak on our behalf.”

But a May poll of likely voters found that more Detroit residents opposed the commission (49 percent) than supported it (41 percent). Among the opposition were charter school critics such as Steve Conn, the former president of the Detroit teachers union who organized city-wide sick-outs, and LaMar Lemmons, then a member of the city’s elected (though basically powerless) school board.

Lemmons said in April that the commission would “allow the mayor to pick charter schools for his friends and campaign contributors.”

Whereas GLEP and charter advocates saw the commission as a Trojan horse for reducing school choice, more hard-line supporters of Detroit Public Schools saw it as a Trojan horse for eliminating the district.

“This was a lack of consensus among Detroiters on how to proceed,” said Naeyaert of GLEP. He pointed out that some Detroit legislators were against the commission but noted that “they were not opposing it for the same reasons we were opposing it.”

Dick and Betsy DeVos have long been influential in Republican politics — top donors to the party, with Betsy the former state chair and Dick previously the GOP’s nominee for governor — and they brought that leverage to bear to help stop the commission.

GLEP had previously tried to oust a legislator who opposed lifting a cap on charter schools, making a primary challenge a credible threat to any Republican who crossed the group and the DeVoses on the oversight commission.

“We urge you to oppose any effort to create a new layer of bureaucracy and limit educational choice in the form of a Detroit Education Commission. There is no example, anywhere, of success for students under this scenario,” the couple wrote in an April letter to state legislators obtained by The 74.

Closely echoing those concerns, Al Pscholka, a Republican representative, later described the proposed commission as “another layer of bureaucracy.”

Ultimately, there was no oversight commission included in the legislation. The House moved forward a bill without it, and the law passed the Senate by a single vote with no Detroit lawmakers supporting it.

Members of the Coalition for the Future of Detroit Schoolchildren said this was Lansing deciding Detroit’s fate for it.

“Detroiters had no say in that solution: No Detroit legislators voted for it; no Detroit legislators were a part of the negotiation,” said Arsen of Michigan State. “This was something that was imposed on Detroit.”

Gov. Snyder signed the bill into the law in June.

The final language included many aspects that the coalition pushed for: $617 million to help the schools avoid bankruptcy ($100 million less than in the original Senate bill); a school accountability and letter-grading system (determined by the state rather than by a mayoral-appointed commission); rules to stop low-performing charters from getting reauthorized; and the creation of a newly elected school board (though key decisions must be approved by a state-appointed financial review commission).

Naeyaert said this is evidence of a compromise: “If I was advocating for something and I got nine out of the 10 things I wanted, I’d definitely be supportive.”

The bill also added controversial provisions to allow uncertified teachers to work in Detroit schools and fine teachers who engage in illegal strikes — clearly aimed at those who had participated in district-wide sick-outs earlier that year to protest horrific building conditions and the prospect of going unpaid.

The DeVos family over the years has donated millions to Michigan Republicans — $3.4 million alone since Jan. 1, 2015, with $1.5 million of that going to GOP state legislators and organizations in the weeks after the bailout bill was approved. Supporters of the defeated commission, including the Detroit Chamber of Commerce and the American Federation of Teachers Michigan, had also donated to many legislators over the years, but much less than DeVos and her family.

Detroit legislators were furious at the outcome, saying wealthy billionaires living far from their troubled city used their clout to ignore local demands.

“You coward. You coward — to even take and put this legislation before us and before my community and not even have one Detroiter in the room to help negotiate this piece. We would have said, ‘Hell no,’ ” state Sen. Morris Hood said in a fiery speech on the Senate floor, referring to the Republican majority. “Guess what? You go into your caucus, and they go into their caucus and do whatever they want to do to my community — the kids I have to look at every day walking up and down the streets. I have to look in their eyes; you don’t.”

Allen, of the coalition, also said the lack of Detroit influence was disappointing: “I was just discouraged that here you have leaders in our state who believe in parental choice, who believe in decisions being made closest to the people that are most affected … and they could not reflect Detroiters’ ability to make decisions for themselves.”

Race and the power wrought by money were issues not far from the surface of the debate in a city where 82 percent of residents are black and 39 percent live in poverty.

“These bills build on the foundation of institutional racism,” argued state Rep. Sherry Gay-Dagnogo, a former Detroit schoolteacher, saying it was outside emergency managers who drove the district’s deficit.

“From our perspective as a community, race plays a huge part,” said Molly Sweeney of the Detroit-based community-organizing group 482 Forward. “Those making decisions aren’t from this community, and that also has race and class all tied up in it.”

482 Forward — which Sweeney said receives some funding from the Skillman Foundation and the American Federation of Teachers — led a social media campaign featuring Detroit residents: “GLEP and MAPSA [Michigan’s charter school association] don’t speak for us.”

GLEP and MAPSA don't speak for us! @MIGOP #mileg #kidsovermoney #istandfor #senatebillsnow #choiceisours pic.twitter.com/m7Y2R0qbhn

— 482Forward (@482Forward) June 2, 2016

Patru said the commission itself would have been a form of unequal treatment and that many Detroit residents rejected it.

“Tens of thousands of black families in Detroit saw bigotry and discrimination in a public policy proposal that would have imposed additional governing bureaucracy on Detroit charter schools, while leaving charter schools in white communities alone,” he said.

Dan Quisenberry, head of the state charter school group and a key commission opponent, said charter advocates and the DeVoses were a moderating influence that helped save Detroit schools from bankruptcy.

“[Some representatives in the House] didn’t want to send any bailout money to Detroit Public [Schools], so the compromise that the DeVoses and others and us were involved in was to get a solution, as opposed to no solution,” he said.

Legislators, though, had strong incentives to save Detroit schools from going under: A district bankruptcy could cost the state billions in pension and other liabilities.

On the issue of local control, Quisenberry pointed to the poll showing significant disagreement in Detroit about the oversight commission. “If I’m a politician trying to say where’s the public support here, it was not clear,” he said. “The residents of the city were not clear what should be done.”

There does not appear to have been any polling in the city on the bill that ultimately passed.

“What does local control mean?” Quisenberry said. “Sixty charter schools operate within the city of Detroit — 70 percent of those are run by Detroiters.”

These moves brought praise from Greg Richmond of the National Association of Charter School Authorizers, one of the foremost national supporters of charter accountability and oversight.

“During the last legislative session, Michigan improved the accountability provisions of their charter school law, both for the schools themselves and for authorizers,” Richmond told The 74 in an email, though he noted that the state still falls in the middle of the pack in his group’s rating of state charter laws.

Nationally, DeVos has advocated for voucher programs — which are usually far less regulated than charter schools — and online schools, which have generally posted dismal test scores. In Michigan, however, groups she’s supported have backed accountability rules, and she personally wrote in favor of letter grades for schools and “aggressive intervention — including closure — of the state’s lowest-performing traditional and charter schools.”

DeVos, though, is clearly no fan of many front-end limitations on charter schools, including a cap on charters and the Detroit oversight commission, which could have restricted where new charters opened.

Allen, who saw the oversight commission as critical to solving Detroit’s educational failure, nonetheless congratulated DeVos in an email she sent soon after her nomination by President-elect Trump, saying, “I am so happy for you. I am happy for Michigan. I am happy for our country. I am happy for our kids.”

Allen acknowledged that the pair were at odds but wrote, “Maybe your appointment, our political differences and Detroit’s unique challenges create an opportunity to do something unexpected, outside of the box, and successful. I am ready to take something on like this that is both big and bold.”

Allen declined to comment on the email, which was released by Greg McNeilly, a political consultant and close DeVos ally.

After being nominated, DeVos pledged support for “local control” of schools. However, her legacy in Michigan points in conflicting directions — she and her husband had outsize influence in the legislation affecting Detroit schools, while local legislators were often sidelined. Under the new law, significant local control is returned to an elected board, but the state will still have sway over how Detroit schools are run — much more so than other districts in Michigan.

“Since DPS has lost 75 percent of their enrollment in the past decade, haven’t Detroit parents already voted resoundingly by fleeing for higher-quality and safer schools elsewhere?” DeVos asked rhetorically in a piece for The Detroit News.

This is perhaps telling: Under DeVos’s philosophy, local control of schools comes not necessarily in voting for an empowered school board but in families choosing schools by what’s often referred to by choice advocates as “voting with their feet.”

Trump has proposed an ambitious federal expansion of school choice, reportedly crafted with advice from the American Federation for Children, whose board DeVos used to chair. Trump has called for taking $20 billion in federal education aid and turning it over to the states as a block grant that 11 million poor children could tap into to exercise school choice. His plans also echo a key AFC tenet: that education funding should follow disadvantaged students to whatever school they attend — traditional public, charter, private, virtual — instead of flowing into high-poverty public schools.

Some right-of-center school-choice supporters say such an initiative could amount to federal overreach and have expressed concern that the Department of Education could end up dictating too many of the parameters for school choice to the states.

“It is good news that there will be a proven school choice champion holding the highest-profile education job in the land,” wrote Neal McCluskey, of the libertarian Cato Institute. “But it needs to be absolutely clear that that does not make Betsy DeVos the national education boss.”

What DeVos’s time in Michigan makes clear is that she may well use the influence she’ll have in D.C. to advocate for her vision of school choice — regardless of what’s being proposed by local officials.

The Dick & Betsy DeVos Family Foundation provided funding to The 74 from 2014 to 2016. Campbell Brown serves on the boards of both The 74 and the American Federation for Children, which was formerly chaired by Betsy DeVos. Brown played no part in the reporting or editing of this article.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)