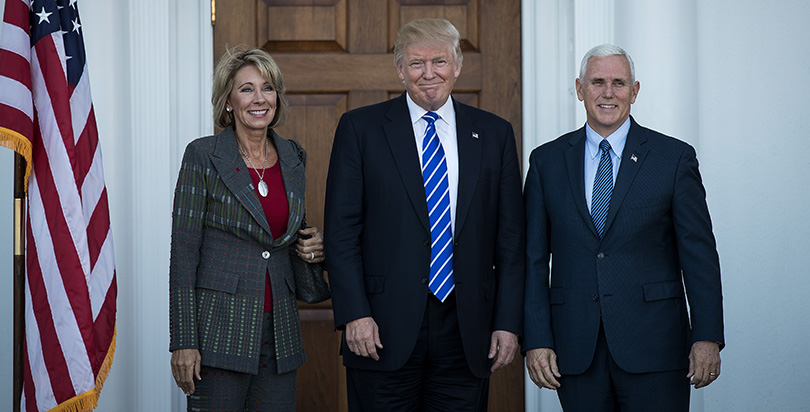

Betsy Devos, Trump’s EdSec Pick, Promoted Virtual Schools Despite Dismal Results

Secretary of education nominee Betsy DeVos has a long history of backing virtual schools, including founding and funding groups that have supported the expansion of online education. Additionally, as of 2006, her husband, Dick DeVos, was an investor in K12, a large network of more than 70 online schools.

Although advocates for virtual education say it is a lifeline for students who struggle in traditional settings, multiple research studies show that online charter schools and other virtual education models post dismal academic results, as measured by improvement on standardized tests.

DeVos, as chairman of the American Federation for Children — she stepped down last week — repeatedly called for expanding virtual schools. In a 2015 statement released through the group about a federal spending bill, DeVos said, “Families want and deserve access to all educational options, including charter schools, private schools and virtual schools. … [V]irtual schools are growing across the country. Greater innovation and choice will contribute to better K-12 educational outcomes for our children.” In 2012, DeVos supported a plan by Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell that including an expansion of online schools.

The American Federation for Children has praised such schools as allowing for “more flexibility and options in education” and includes “virtual learning” as part of its mission statement.

Matt Frendewey, a spokesperson for the group, said that it primarily focuses on private-school-choice programs — such as vouchers or tax credits — but that it also advocates for the expansion of additional options, including online schools. “We’ve long supported all forms of choice,” he said. “We believe parents should be able to exercise the greatest number of choices, including public schools, public charter schools, virtual schools, online courses, blended learning, homeschooling and private schools.”

In 2013, the American Federation for Children put out a sharply critical statement after New Jersey’s school chief, Chris Cerf, declined to authorize two virtual charter schools. The group said the decision “depriv[es] students of vital educational options.”

Another group DeVos founded and funded, the Michigan-based Great Lakes Education Project, has also advocated for expansion of online schools. (DeVos sat on the group’s board until last week.) In a 2015 presentation to the the Michigan Board of Education, the group’s executive director, Gary Naeyaert, argued for “full school choice” including virtual schools.

In an interview, Naeyaert said that his group doesn’t privilege online schools over other options and supports accountability for any low-performing school. “Our position [on virtual schools] is the same with any [school]: Are the kids learning? Is the money being handled responsibly? We don’t make a big distinction with whether the environment is brick-and-mortar.” Naeyaert pointed out that many virtual education programs in Michigan are run by school districts rather than charter networks.

DeVos highlighted virtual schools as an important part of the “educational choice movement” in a 2013 interview with Philanthropy Roundtable. In a 2015 speech, DeVos praised “virtual schools [and] online learning” as part of an “open system of choices.”

“We must open up the education industry — and let’s not kid ourselves that it isn’t an industry,” she said in the speech. “We must open it up to entrepreneurs and innovators. … This is how a student who’s not learning in their current model can find an individualized learning environment that will meet their needs.”

In 2006, as reported by Politico, Betsy DeVos’s husband Dick noted in a financial disclosure statement while he was running for governor of Michigan that he held an investment interest in K12 Inc., a large, for-profit chain of online schools. It is unclear if the DeVoses are still investors. A spokesperson for K12 said, “As a public company we don’t disclose who our investors are, and frankly, depending on how specific investors hold shares, we may not be aware of every individual shareholder of K12.”

The Trump transition team did not respond to a request for comment.

Nate Davis, the executive chairman of K12, responded enthusiastically to DeVos’s appointment. “DeVos has been a longtime advocate for strengthening public education and empowering parents with the freedom to choose schools that best meet the needs of their children,” he wrote in a column for The Hill. The group Public School Options, which backs online schools, also praised the appointment.

It is not clear to what extent DeVos, if confirmed as secretary of education, would or could promote online education. The Obama administration backed the expansion of charter schools through its Race to the Top grant program, but the subsequent passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act has significantly reduced federal authority. Still, DeVos could leverage her office’s bully pulpit as well as federal charter school grant programs. Trump has promoted sending federal dollars to states to expand school choice — presumably including online schools — and his transition site promises to make “post-secondary options more affordable and accessible through technology enriched delivery models.”

Greg Richmond, head of the National Association of Charter School Authorizers, said, “As the secretary of education, there are limited ways that Ms. DeVos can provide leadership on that front. One thing she can do is ensure that virtual schools, and for that matter any charter school run by a for-profit company, accounts for the federal dollars they receive.

“For example, any school that receives federal special education dollars must actually use those dollars for special education students and publicly account for those dollars,” he said.

Online charter schools have faced a wave of negative press, particularly after a large-scale 2015 study found that students who attended them lost a huge amount of academic ground. The study found that kids who returned to brick-and-mortar schools saw big jumps in test scores upon doing so. “Academic benefits from online charter schools are currently the exception rather than the rule,” the report’s authors wrote. Notably, Michigan was one of the few states where students at online charters performed comparably to other students, according to the research.

Several studies suggest that exclusively online education is likely to produce significantly worse academic results than brick-and-mortar options. Online programs may have the potential to expand access to more advanced courses or may be an option for students who can’t attend physical schools due to illness, for instance.

Online charter operators have proven politically influential in many state capitols. In an essay for The 74, former Tennessee commissioner of education Kevin Huffman described his failed attempts to shut down a low-performing network of schools in the state — K12 Inc., the same company Dick DeVos was invested in as of 2006. (At the time, K12 responded that the schools they ran were not low-performing and were unfairly targeted for closure.)

DeVos’s support for online schools would seem to put her at odds with some charter school advocates, highlighting a tension between choice advocates who emphasize accountability and student achievement and those who argue that choice serves as its own form of accountability.

Earlier this year, three groups that support charter schools published a report calling for more stringent oversight and regulation of online charter schools. “The well-documented, disturbingly low performance by too many full-time virtual charter public schools should serve as a call to action for state leaders and authorizers across the country,” according to the paper, released by the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, the National Association of Charter School Authorizers, and 50Can.

Frendewey, of the American Federation for Children, said he did not think his group had been approached about joining the report because AFC focuses primarily on expanding access to private schools, as opposed to charters. “It’s highly unlikely we would [have joined the report] not because of the content, but because of our mission, which is private choice,” he said.

Frendewey noted that his group has supported quality-control measures for private-school voucher programs: “Our [model] legislation often includes commonsense accountability.”

Richmond, whose group co-issued the the paper, said he is not worried about DeVos’s position on the issue: “I’m not concerned that Betsy DeVos supports virtual schools, because we support them too — we just want them to be a lot better.”

The Dick & Betsy DeVos Family Foundation provides funding to The 74, and the site’s Editor-in-Chief, Campbell Brown, sits on the American Federation for Children’s board of directors, which was formerly chaired by Betsy DeVos. Brown played no part in the reporting or editing of this article. The American Federation for Children also sponsored The 74’s 2015 New Hampshire education summit.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)