In One of the Few States to Mandate Personalized Learning, Coordinators Key to Keeping Vermont Students Engaged Before — and Now During — the Pandemic

When school went remote last spring, Terry Berger, the internship coordinator at Leland and Gray Union Middle & High School in Townshend, Vermont, faced a challenge unfamiliar to most teachers: supporting her two dozen students learning not in the classroom but on the job site.

Problem-solving on the fly, Berger made a Facebook group for her class where she could respond to their questions and concerns. Through the page, she helped her students navigate a tricky spring, and she then stayed in touch through the summer and fall — even with her graduated seniors.

“Legally they’re no longer my responsibility,” said Berger. “But the work-based learning Facebook page has been a really good way just to keep kind of connecting and checking in.”

Berger’s been known to land internship placements for her students while in line at the local deli or hardware store and then drive teens to their job sites herself, if needed. Pre-COVID, coordinators like her were already the linchpin of Vermont’s personalized learning program. In 2013, the state became one of the few in the country to mandate personalized learning, passing statewide legislation requiring all public high schools to establish a network of personalized learning options, which included specialized online classes, dual enrollment at local colleges, project-based classes, and work-based learning at internships.

Some schools opted to add a devoted staff member like Berger to help coordinate these new options. Now this fall, many Vermont schools have transitioned their already-established personalized learning programs to fit the needs of hybrid and remote instruction — with coordinators like Berger front and center.

As education leaders nationwide scramble to put strong distance learning options into place, and as personalized learning programs in Vermont morph to fit the demands of COVID-era schooling, the importance of having a staff member devoted to helping students navigate new challenges may only be growing — in Vermont and beyond.

I became familiar with Berger and coordinators like her while researching for my senior thesis at Brown University. Having grown up and graduated from public schools in northern Vermont myself, I was well aware of the state’s push for personalized learning. But the anecdotes I heard from friends and teachers described schools across the state that were each taking different approaches to their new programs. So for my thesis, I set out to determine which factors were related to increases in student engagement and equity. One component emerged from my data as the strongest link to success: the presence of a coordinator, known in Vermont as pathways coordinators.

In 2019, I surveyed Vermont public high school principals to learn about their schools’ personalized learning programs. Principals at 35 of the state’s 60 public high schools completed my survey, and out of those 35 schools, 19 indicated that they had a devoted personalized learning coordinator on staff. This month, I reached back out to those 19 school leaders to see how the pandemic had affected their staffing choices.

Eight out of eight Vermont principals who responded to my inquiry indicated that their personalized learning coordinator positions have been either maintained or expanded this year, despite many schools facing tightened budgets.

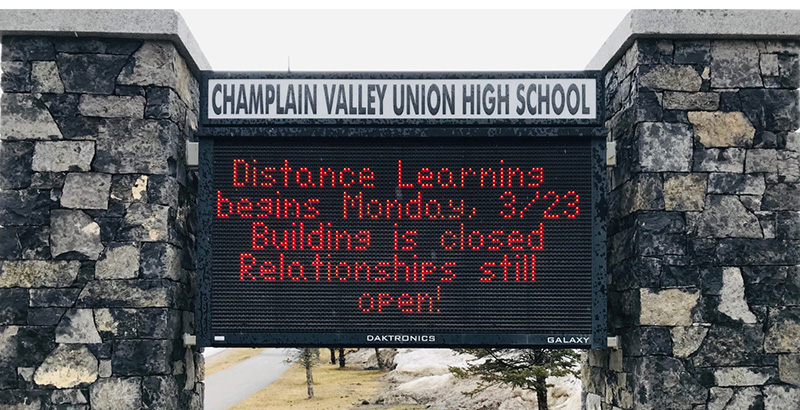

Adam Bunting, principal of Champlain Valley Union High School, told The 74 over email that right now pathways coordinators are “more important than ever.”

“We have to build authentic, purposeful relationships that count,” Bunting wrote.

My analysis, published in June by Brown University’s Taubman Center for American Politics and Policy, backs up Bunting’s assessment. It found that the presence of the coordinator role was the single biggest factor linked to schools having built engaging and equitable personalized learning programs. The paper analyzed factors such as school leadership, professional development, inclusion of student voice and advisory type. Coordinators emerged as the key component of successful programs. On average, schools that had a devoted personalized learning coordinator on staff reported personalized learning participation rates 5 to 15 percentage points higher than schools without one.

A significant portion of that bump may represent students who would not have had access to personalized learning programs if it weren’t for their coordinator. Coordinators assume a number of responsibilities essential to ensuring equitable access to personalized learning opportunities. They publicize dual enrollment and online learning options, help students navigate the labyrinth of paperwork for enrolling in college courses, set students up with internship placements and coordinate transportation.

Patty Davenport, pathways coordinator at Springfield High School, often works in the evenings to ensure that her students successfully log on to their dual enrollment and online learning courses. She makes certain she’s available via text in case of any glitches.

“Where these tasks go unfulfilled or under-fulfilled, it is often the students who do not have as strong parent advocates or whose parents are less college-savvy who miss out on opportunities,” my paper points out. Now during COVID, more populations get tacked onto the list of vulnerable students: those without access to a stable internet connection, those with a noisy home environment, those who are food insecure. Having someone to turn to when roadblocks arise may be even more critical during the pandemic.

Vermont’s brand of personalized learning, known across the state as the Flexible Pathways Initiative, distinguishes itself in a number of ways from other personalized learning models. A 2016 iNACOL report described its effort as “the most comprehensive statewide policy approach” to personalized learning in the country.

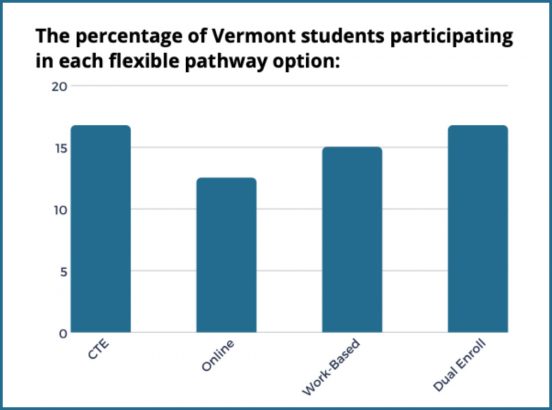

All seventh- through 12th-grade students are required to create “personalized learning plans” that map their anticipated course of study through academic and flexible pathway learning options. Not all students must participate in the flexible pathway options — up to 60 percent do — but all students must make intentional choices about their academic plans through reflection on their skills, interests and curiosities.

“Everybody has an IEP, in effect,” explained state Sen. Dick McCormack, referring to the Individualized Education Programs that are mandated for special education students and tailored to their needs. McCormack chaired the Senate education committee when Vermont’s personalized learning bill was passed. “You want some kind of responsiveness to the fact that different kids learn differently.”

Perhaps most importantly, while Vermont’s model incorporates online components, it doesn’t rely on tech as the focal point of student learning. Personalized learning approaches are often criticized for over-using computer-based curricula and de-emphasizing the live teaching experience. Instead, Vermont’s Flexible Pathways Initiative leans toward a Dewey-esque model of personalization, where learning is guided by student interests and comes from real-world experiences.

For many Vermont students, personalized learning means showing up to work at an internship, planning out an independent project or tuning in to a college-level course.

Of course, the Green Mountain State is not exactly a representative sample of the country at large. Its population of roughly 620,000 is over 94 percent white and its schools are funded at $18,290 per student—the fifth-highest funding level in the country. But with over 38 percent of its students receiving free or reduced-price lunch, and with rural poverty as a persistent barrier to student achievement, Vermont schools have a number of issues to navigate if they seek to serve students equitably.

Even before the virus, but especially now that distance learning is a central part of the equation for many districts, coordinators have been crucial to equitable access.

“Students need to be seen, supported and understood,” my Brown University analysis concludes. “[Personalized learning] programs must prioritize personal relationships between students and faculty for schools to know how to effectively guide and support their students.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)