Does Personalized Learning Work? The Research Is Too Scant, Too New and Too Nuanced to Give a Clear Yes or No — At Least for Now

Hear that? It’s the sound of personalized learning cracking under the pressure.

Exhibit A: Recent headlines concerning two hotly anticipated studies of the middle school math program Teach to One. The first study, a federally funded look at five schools using the personalized learning model in Elizabeth, New Jersey, found it had no significant impact.

The second, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, found strong growth in math in 14 schools throughout the country using the program but could not correlate the greater gains to Teach to One.

Given the hype — positive and negative — surrounding personalized learning, interest in anything that might validate or deflate the model’s potential is intense. And at first blush, the headlines that topped stories about the studies seemed to deliver verdicts: One “cast doubt” on Teach to One’s utility, while another declared it had “no effect” on math scores.

Read deeper, though, and it turns out that the studies did not in fact find the program ineffective. And that disconnect, say experts, illustrates a frustrating reality: Research on personalized learning is too scant, too new and too nuanced to provide the kind of thumbs-up, thumbs-down statements longed for by education watchers.

Neither study used a methodology designed to isolate the math program’s impact on student learning, according to outside researchers with expertise in personalized learning. Still, both represent important contributions to the small but growing body of information about which strategies might work, and under what circumstances.

And yet, given the investments by major philanthropies, education advocacy organizations and technology pioneers, both for-profit and nonprofit, in personalized learning — not to mention the attendant buzz — the pressure for a definitive declaration about its effectiveness is relentless.

“John and I joke a little that for the last two years we’ve been on the presentation circuit,” quipped Betheny Gross, associate director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, referring to the steady stream of queries directed to her and to another go-to personalized learning scholar, the RAND Corp.’s John Pane.

The public’s desire for broad, declarative conclusions notwithstanding, education research in general often results in narrow findings. Personalization — a combination of strategies that tailor instruction to individual students’ needs, aptitudes and interests, including online education, flexible approaches that allow students to work at different paces and project-based classes — adds layers of complexity.

“It’s a variety of things in a variety of settings,” explained Gross. “There’s a ton of variation found in terms of impact.”

Gross and Pane are among a number of experts who warn that evaluating strategies as diverse and complex as the efforts grouped together under the heading of personalized learning is so complex that the process is painstaking, slow and poorly suited to the kinds of bottom-line takeaways policymakers and education watchers tend to push for.

“I would be worried that a message comes out that personalized learning is something that can’t ever work,” she said.

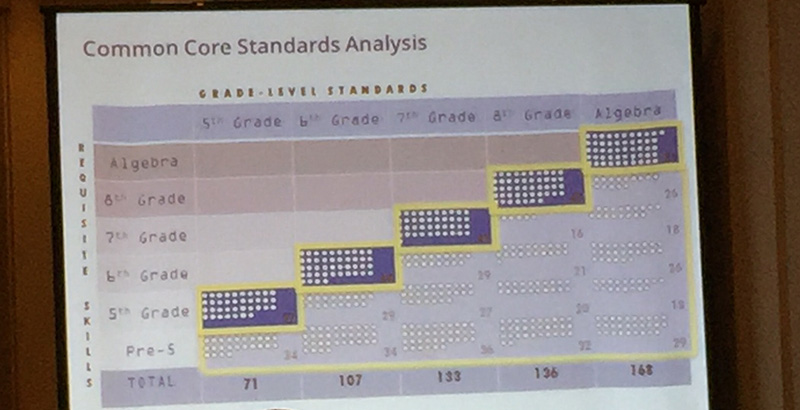

In a Teach to One classroom, students work in small groups, according to math skills they have not yet mastered, in a single classroom. The day’s lessons are customized for each student based on past outcomes, with the help of a computer algorithm. The idea is that plugging holes in students’ understanding will move them steadily toward grade-level performance.

Teach to One is currently used in 39 middle and high schools in 11 states, serving almost 10,000 students. In theory, the program should solve a thorny dilemma: how a teacher can meet every student at her level in a classroom populated by some kids who are years ahead and some who are behind — and behind on a variety of different skills and concepts.

The first study was conducted by Columbia University’s Consortium for Policy Research in Education at Teachers College. It was part of a $3 million U.S. Department of Education “Investing in Innovation” grant awarded in 2015 to New Classrooms Innovation Partners, the nonprofit behind Teach to One. The study compared student performance on annual state math assessments in five New Jersey middle schools with test scores at 16 demographically similar schools in the same district. Teach to One students did neither worse nor better.

The state tests, however, measure proficiency — whether students score at or above grade level in a subject. By design, the study would not reflect strong growth among students who started out years behind.

In addition, the narrative portion of the Columbia researchers’ report is a minefield of caveats. When Teach to One’s algorithm creates individual student pathways, the computer program reaches back into lessons from past grade levels to find material to help students backfill missing concepts. The district or teacher using the system can set a floor — a limit to the number of years back this process can go. In the case of the New Jersey study, the district changed the program’s parameters, including this floor, several times, according to the researchers.

“Similarly, some schools asked that [Teach to One] incorporate ‘ceilings’ that limited how far ahead students could go in relation to grade-level standards,” noted the report. “While some students were fully capable of accelerating into above-grade content, particular schools and districts preferred that such students instead review and deepen their understanding of grade-level material. Finally, in addition to these changes, some schools requested a more focused ‘test-prep’ period during the weeks directly prior to the administration of high-stakes state assessments. This further prioritized grade-level material above and beyond the floors and ceilings that may have been imposed throughout the school year.”

A final twist: The district chose to evaluate students’ proficiency on algebra at the end of the academic year, not eighth-grade content — an option in New Jersey — making it further unclear whether students had been exposed to the material they were to be assessed on.

“In sum, these analytic complications, which are likely common to any evaluation of any personalized learning model, obviously warrant further consideration,” researchers noted.

The second study was conducted by MarGrady Research and examined growth on the Northwest Evaluation Association’s Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) test. It found that students in Teach to One classrooms saw math score gains 23 percent higher than similarly situated peers. Schools that used student growth to assess classroom performance saw the highest gains. Yet the study did not include controls that would determine conclusively whether that growth was attributable to Teach to One or to another factor, such as extra time, school climate or teacher talent.

Because schools often try several strategies at the same time in the hope of landing on something that helps students, the New Jersey classrooms likely had multiple interventions underway. Much more tightly controlled research parameters would be necessary to isolate the program’s effect on student learning, researchers said.

“Personalized learning is intended to be a broad, schoolwide initiative,” said Pane. “You would not want to separate teachers into a control group and an effect group because then they can’t collaborate.”

New Classrooms CEO Joel Rose said he has drawn two conclusions from the reports. “What the MarGrady study shows is that when we can truly meet kids where they are, they accelerate,” he said. “And in places where the accountability system allows a focus on growth, they grow even more.”

The ultimate aim, he said, is to hold school systems accountable for graduating students ready for a career or college: “If a student walks into seventh grade four years behind, the best way to ensure that student is college- and career-ready is maybe not to focus on seventh-grade material.”

Gross also questioned whether research can take into account how well a personalized model is being implemented. Because personalization is an array of potential strategies and interventions, not a specific method, teachers may be more comfortable with or enthusiastic about some parts of a bundle of strategies than others.

This will be something to watch as research looking at the widely adopted Summit Learning platform begins to appear, she said, adding that she has visited schools where it appears teachers are spending more time on some portions than others.

“It’s a pretty complicated model, and it requires quite a lot of capacity to implement,” she said.

In addition to conducting long-term research on personalized learning, Pane has authored a paper on implementing individualized approaches in the absence of a critical mass of research. Studies that do not yield the kinds of thumbs-up or thumbs-down findings policymakers and the public are eager for should instead be mined for information on how to strengthen implementation, he and others said.

“We should be trying to do more research than is being done right now,” said Pane. “The whole field needs to be focusing on the questions coming up here.”

“Sadly speaking, the process of research is not a fast one,” he added. “The field is moving much faster than the research.”

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, Chan-Zuckerberg Educational Alliance and Charles & Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation provide funding to New Classrooms Innovation Partners and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)