In NYC and Beyond, Foster Youth Data Still a Blank Space in State Report Cards Four Years After Federal Education Law Enacted

School achievement data for foster youth, considered one of the most vulnerable and least tracked student groups, will not be reported for the nation’s largest school district for at least another year despite its being mandated by federal law.

The New York City Department of Education says it will identify which students are foster youth in the pupil data it sends to the New York State Education Department starting with the 2019-20 school year. That information should have been on hand with the state beginning with the 2017-18 school year under mandates spelled out in the Every Student Succeeds Act, the federal K-12 education law adopted in late 2015.

New York City is not alone. More than half of New York state’s 721 districts did not identify a single foster youth student in 2017-18 — despite their numbers being estimated at 11,000 statewide — and, as of April 2019, 33 states across the country had yet to report any test score data for foster youth.

In New York City, where the state’s concentration of foster youth is greatest, the delay means their test scores and high school graduation rates won’t be broken out and publicly available until at least late 2020 or early 2021. That’s when the state is expected to release its 2019-20 report cards — a public database that provide parents and others with information on state-, district- and school-level performance and progress each year. The 2017-18 report cards are the most current; the 2018-19 report cards are likely expected early next year.

The number of school-age foster youth in the city varies by source; Advocates for Children of New York reported 4,500 students in a “snapshot” count in May, whereas the district recorded about 7,800 during the 2017-18 year. In most cases, foster youth are children who’ve been removed from their parents or guardians by a child welfare agency and placed into alternative care, which can range from living with a relative to staying in an emergency shelter.

Without this mandated separation of data, the performance and academic challenges of foster youth and other high-risk groups, such as homeless students, often “gets lost” within sweeping district and statewide rates, effectively “masking the inequities in our system,” the Data Quality Campaign’s Paige Kowalski said.

“When we don’t shine a light on individual groups, it’s hard to figure out what we have to tackle; where we have to put our resources and time,” said Kowalski, the campaign’s executive vice president. Already existing “subgroups” that states have to report on include students with disabilities and English language learners.

It’s unclear whether the lag constitutes a failure to comply with the law. The U.S. Department of Education — speaking generally — appeared to place the onus on states for any district-level reporting delays, writing in an Oct. 4 statement, “If a district were not collecting data for those students, and the state did not have another way to collect and report that information, the state would be out of compliance.”

New York’s state Education Department was unable to confirm how many districts as of 2018-19 were providing information on foster youth to the state, but it said 380 of its 721 districts, or about 53 percent, reported no foster youth during the 2017-18 year. Spokespeople for two of New York’s other largest districts, Buffalo Public Schools and Syracuse City School District, confirmed separately that they currently identify both homeless and foster youth.

A New York City DOE spokesperson didn’t offer a clear explanation as to why its subgroup reporting for foster youth is rolling out late. They noted that the DOE collects and disseminates some data on foster youth, such as the number of students on track to graduate, in a separate annual department report. “Data helps educators, families, and community members understand the progress our schools are making, and we work with the State to share requested information,” the spokesperson wrote in an Oct. 3 email.

As required, New York City schools did identify homeless students in its state-submitted data for both the 2017-18 and 2018-19 school years, the spokesperson said. The state has released test scores for New York City’s homeless students, but not their graduation rates, which require multiple years of data to compile and are expected to go public when the 2018-19 report cards are released. About 1 in 10 of the city’s 1.1 million public school students, or roughly 115,000 young people, are deemed homeless or “in temporary housing,” which includes living “doubled up” with other families or staying in a shelter, hotel or motel.

Foster and homeless youth are considered two of the most at-risk student populations in the U.S. While each have unique challenges, both groups must cope with uncertain or unstable home environments, school disruptions and emotional trauma that can hurt their standardized test scores and lead to higher dropout rates.

Yet even four years after ESSA’s passage, reporting setbacks in New York City, New York state and across the country continue — due in part, experts say, to ESSA’s vague guidelines that curtailed the federal government’s control over state education policy and promoted local autonomy. There are also complications in collecting foster youth and homeless student data when it requires education officials to coordinate with child welfare agencies.

Even once states have the data from their local districts, they have considerable flexibility in deciding when to make the information public.

At this point, though, New York and its districts — along with other states — have “had four years to get this done,” Kowalski, of the Data Quality Campaign, said. “That’s enough time.”

Graduation rates, test scores far behind their peers

The student achievement data published by the state Education Department so far for New York City homeless students and a small number of foster students statewide underscores their challenges in school.* Test score data for 2018-19 are already up, ahead of the formal report cards’ release:

● 35 percent of NYC homeless students in third grade are proficient in English, compared with 53 percent of all students districtwide and 52 percent statewide

● 23 percent of NYC homeless students in seventh grade are proficient in math, compared with 42 percent of all students districtwide and 43 percent statewide

● Half of NYC homeless students scored proficient on their 2017-18 chemistry Regents exam, 9 percentage points below the district average and 22 percentage points below the state average

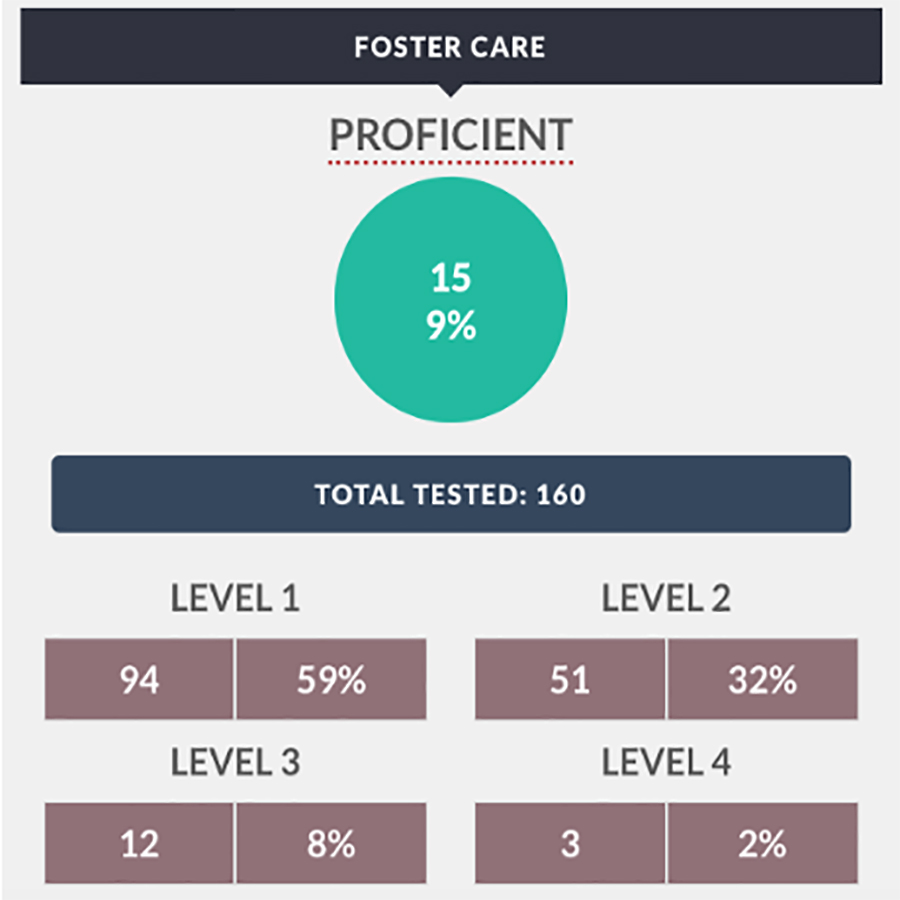

● At the state level, 9 percent of seventh-graders in foster care (from a small sample) are proficient in math — the lowest of all student subgroups

*Note: Students with disabilities and English language learners regularly score below homeless students.

Research culled outside of state databases also highlights markedly lower-than-average graduation trends. In 2016-17, NYC students who had been homeless at some point in high school graduated at a rate of 56 percent, compared with the 74 percent rate citywide, according to the Institute for Children, Poverty & Homelessness. That same year, only 16.3 percent of the city’s foster youth were on track to graduate in four years.

Data reporting for the purposes of ESSA works like this: School districts have to self-report student enrollment and demographic data, including pupils’ subgroup status, to the state Education Department every year.

The state is then responsible for compiling districts’ data by subgroup and posting the information annually in its report cards. ESSA directs states to publish test scores and graduation rates in particular for foster and homeless youth. States can release more information on these students if they choose — Indiana, for example, provides data on suspension and expulsion rates for foster youth.

New York’s state-level 2017-18 report card includes broken-out test scores for homeless students and at least some foster youth. In this way, New York is actually “leading” many states, Kowalski said. Only 17 states published similar data for these students as of April, according to a Data Quality Campaign report, and 28 didn’t report outcomes for either group.

The state’s data, however, are still incomplete. There were a reported 152,839 homeless students in New York state public schools in 2017-18 — but 125,463 were identified as homeless in report card enrollment data. Ninety-one districts out of 721 identified no homeless students that year, according to the state.

The gap is even more stark for foster youth: While there were an estimated 11,000 school-age children in foster care in New York state as of late 2017, only 2,573 were listed in enrollment data for that school year. Each grade level accounted for some 200 or fewer foster students.

The scarcity of foster-youth-specific data thus far isn’t lost on education equity groups like Advocates for Children of New York.

“It’s easy to overlook students in foster care because their numbers are relatively small, but given the many challenges they face, they require a greater level of attention and targeted support from school districts,” staff attorney Chantal Hinds said in a statement.

The state did not break out high school graduation rates for either foster or homeless youth across its 2017-18 report cards. It needed four years of ESSA subgroup data, which it got with the 2015 freshman cohort that just graduated in June. The state Education Department confirmed it will start disclosing those rates based on the districts that provided the needed data in the 2018-19 report cards. Though there is no set publish date, the department noted for reference that it released the full 2017-18 report cards beginning in January 2019.

No punishments per se

A large reason for the often staggered publication of report cards in New York and other states, experts say, is the looseness of ESSA’s deadlines. Although states were directed to separate out test scores and high school graduation rate data for foster and homeless youth starting with their 2017-18 report cards, there is no hard deadline for actually publishing the information — or any clear repercussions for states that take their time doing so. An annual Dec. 31 publishing deadline existed when ESSA initially passed, but Congress tossed out the Obama-era regulation, along with others, in 2017.

“The enforcement remedies are not as strong as they would be if there had been a firm deadline,” said Anne Hyslop, a former senior policy adviser with the U.S. Department of Education. “It’s a judgment call — if data is a year late, is that too long?”

Hyslop, who now serves as assistant director for policy development and government relations for the Alliance for Excellent Education, said the state holds responsibility for “setting out a clear deadline and process for when this data is due from districts,” making sure that there are clear definitions for who counts as a foster or homeless student to ensure consistent data reporting, and by saying “[this reporting] is going to be contingent on us giving you your federal money.”

She added, though, that “the state can’t do it alone. The district ultimately is the one that is interacting with students and is gathering the data. They both have a role to play.”

A state education department spokesperson said the department has “been proactive in communicating” districts’ responsibility to report student subgroups. They added, “While there are no ‘punishments’ per se” for districts that aren’t yet identifying those groups, “failure to report could, for instance, result in loss of funding for a district.”

The department didn’t directly provide reporting deadlines for New York’s school districts but cited a timeline that outlines when certain types of student data are due.

Kowalski does give New York state credit for its decision to leave a visible space in its report cards for data it doesn’t have yet, rather than not mentioning it at all.

“It takes courage, because someone is going to pick up the phone and say, ‘Where’s our kid?’”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)