In Case the School Choice World ‘Dreaded,’ Justices Appear Open to Religious Charters

Chief Justice John Roberts asked tough questions of both sides in a matter with important ramifications for the future of public schools.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Poking both sides in a dispute with potentially huge ramifications for education, Chief Justice John Roberts could cast the deciding vote on whether charter schools funded with public dollars can be free to practice religion.

Oklahoma’s high court ruled last year that a Catholic charter school — the first of its kind in the nation — violates state and federal law. Initially, Roberts appeared to agree that the stakes seemed greater than those in earlier cases about religious schools taken up by the court.

“This does strike me as a much more comprehensive involvement,” Roberts said.

But later in the arguments, Roberts indicated that there may be less daylight between those earlier cases and the matter of the Oklahoma school. In one, a religious school wanted to participate in a state program that provided playground paving materials. Another focused on whether a Christian school could serve students who received tax credit scholarships.

Roberts asked Gregory Garre, a former U.S. solicitor general considered to be one of his legal “disciples,” if the test in this case was whether the St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School was “a creation and creature of the state.” Garre argued the case for Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond, a Republican who sued the school and the charter board.

“All of those” parties in the previous cases were state actors, Roberts said, “and we held that under the First Amendment, you couldn’t exclude people because of their religious belief.”

With Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s recusal, the four remaining conservative — and mostly Catholic — justices were sympathetic to the school’s petition. Justice Brett Kavanaugh questioned how the state could prevent St. Isidore from opening a charter without running afoul of constitutional protections against religious exclusion.

“All the religious school is saying is ‘Don’t exclude us on account of our religion,’ ” he told Garrre. “When you have a program that’s open to all comers except religion …that seems like rank discrimination.”

The debate over religious charter schools has captivated — and divided — school choice and religious advocates nationwide since early 2023, when Catholic church leaders in Oklahoma City and Tulsa first asked the state to grant a charter to St. Isidore. The case has rocked the charter sector at a time when many Christian conservatives, emboldened by President Donald Trump’s election, have pushed to infuse more biblical teaching into public classrooms.

‘One particular faith’

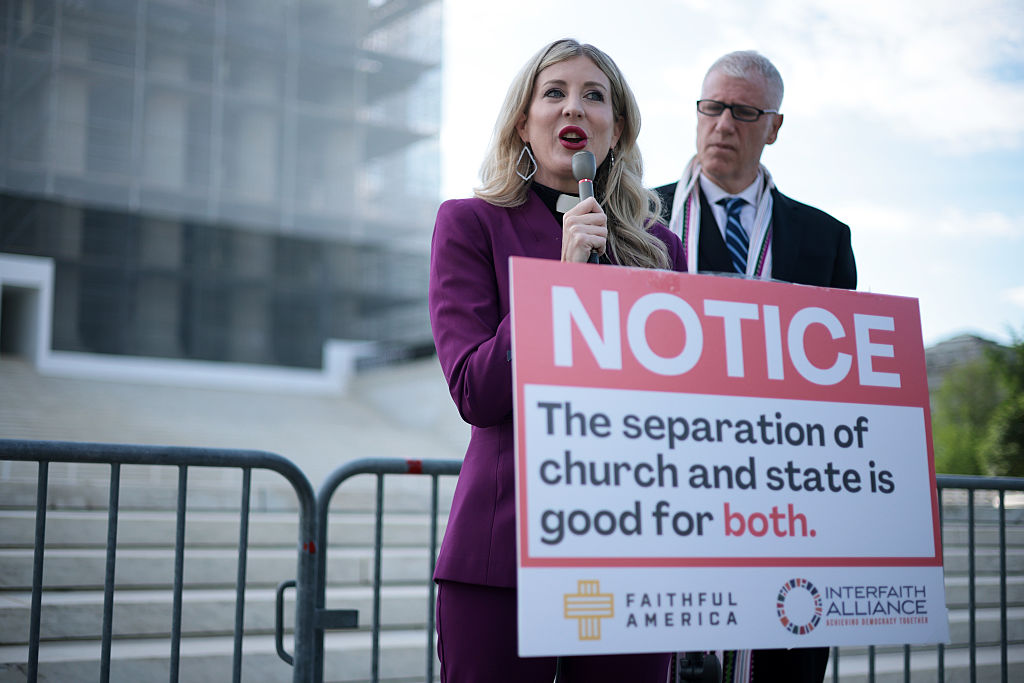

The scene outside the court, where supporters and opponents alike gathered on the plaza, demonstrated the high stakes surrounding the case.

“Faith flourishes best when it is supported voluntarily,” said Rev. Paul Brandeis Raushenbush, president and CEO of Interfaith Alliance and the great grandson of Justice Louis D. Brandeis. “Will our government endorse one particular faith with taxpayer dollars? We believe the answer must be no.”

Nearby, a black-robed choir from a Virginia Christian school sang hymns and EdChoice, an advocacy organization, organized a rally in support of St. Isidore.

Nicole Stelle Garnett, the Notre Dame law professor who crafted the legal argument that inspired the school’s application, took photos with her students and prayed with them before entering the court. Walking through the door, she said, brought back memories of her year as a clerk for Justice Clarence Thomas.

That’s when she became friends with Barrett — the reason, many believe, the justice recused herself. The two taught at Notre Dame, were neighbors in South Bend, Indiana, and their children grew up together. Following the arguments, she said she was still processing the debate. But she later issued a statement saying that the court made “abundantly clear that Oklahoma cannot discriminate against religious organizations in a program that supports privately operated schools.”

As Roberts noted, the court’s previous cases on public funds for religious education focused on whether states must include faith-based schools in voucher-like programs. But in the Oklahoma case, leaders chose to directly fund a school that teaches Catholicism — a leap, many argue, that would violate the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause and clearly entangle government with religion.

“These are state-run institutions,” said Justice Elena Kagan, one of court’s three liberals. “They give the charter schools a good deal of curricular flexibility, because that’s thought to be a good educational thing. But with respect to a whole variety of things, the state is running these schools and insisting upon certain requirements.”

Oklahoma attorney general Drummond, backed by 17 states, made the same argument last year to the state supreme court, parting ways with most of his conservative state’s political leaders, who support the school’s application. They include Gov. Kevin Stitt, who attended the oral arguments, and state Superintendent Ryan Walters.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson drew a line between the Oklahoma school and the previous cases in which religious groups sought inclusion in a state program, such as one that provided access to playground surfacing materials. In this case, she said, the religious school seeks to be exempted from state charter law, which requires schools to be non-sectarian.

“As I see it, it’s not being denied a benefit that everyone else gets,” she said. “It’s being denied a benefit that no one else gets, which is the ability to create a religious public school.”

‘Boomerang effect’

Some of the opposition to religious charters comes from unexpected quarters. The libertarian Cato Institute’s Neal McCluskey, for example, is a staunch supporter of private school choice. But he warns that allowing explicit religious teaching in charter schools would “dangerously entangle the state with religion.”

If Roberts sides with Drummond, the 4-4 decision would allow state supreme court decision to stand. But if the court returns a 5-3 ruling, states that want to avoid religious charter schools could require most board members to be public officials, McCluskey said.

As Justice Neil Gorsuch suggested, proponents of religious charter schools may end up with more state control than they want.

“Have you thought about that boomerang effect for charter schools?” he asked.

A ruling in favor of St. Isidore would “cause uncertainty, confusion and disruption for potentially millions of schoolchildren and families across the country,” Garre told the court.

But the extent of that impact could vary by state.

In Virginia, for example, school districts authorize and have tighter control over charter schools, which makes them more like state actors, said Carol Corbet Burris, executive director of the Network for Public Education and a frequent critic of charter schools.

In Ohio, by contrast, nonprofits are among the organizations that can authorize charters, and for-profit companies are involved in running over half of them.

“For years, charters have benefited from being in a nebulous space between public and private,” Burris said. She notes that charter schools, for example, received paycheck protection program loans during the pandemic, but public schools didn’t. “They claim public when it is in their interest, private when it is not. There is a reason that this is the case that the charter world dreaded.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)