In California, High Schools Are Partnering With Businesses, Community Colleges to Get Students College- and Career-Ready

The city mantra that greets visitors driving through Woodland is “The Food Front,” but high school students in this rural stretch of northern California may not even know the half of it.

“They’re surrounded by farmland,” said John Purcell, head of vegetables research and development at Bayer Crop Science, a major agriculture science player in the region. “But they just don’t understand really all that goes into modern food and agriculture. And I think that’s what’s so exciting about this opportunity.”

If all goes according to plan, by next year Bayer will be in a partnership with Woodland Community College and a nearby high school to make good on a program that more than 100 schools have rolled out domestically and overseas.

Known nationally as P-TECH, short for the Pathways in Technology Early College High School, the program is now gaining a foothold in California. The six-year program teaches college courses to high school students and creates a smooth transition into a community college. That’s all en route to an associate’s degree for which there’s economic demand, with numerous job-training experiences during the process.

The P-TECH model first took root in Brooklyn eight years ago as a collaboration between IBM and the local K-12 and college systems. IBM then helped more than 100 P-TECH schools across the country and the world. Now hundreds of businesses serve as partners to P-TECH by mentoring students and offering paid internships, working with educators to design industry-relevant curricula, and being at the end of a school-to-workforce pipeline to hire P-TECH graduates. Early results suggest high school students in the program are college-ready at higher rates than students in other New York City schools.

Woodland’s focus will be on a set of courses that students can use to springboard into agricultural disciplines, such as animal science, plant science, mechanics and environmental science. There’s even a need for drone specialists and graduates in information technology more broadly “for mapping out the fields, for being able to offer pesticides, for looking at irrigation, so there’s a whole IT component in there as well,” said Ioanna Iatridis, dean of career technical education and workforce development at Woodland Community College. The high school partnering with the college to roll out the program, Pioneer High School, is literally next door to the college campus, so the students at Pioneer have long-standing exposure to Woodland. “The proximity makes it nice and comfortable,” she said.

California’s farming communities need skilled workers in large part because agriculture “is becoming more technologically sophisticated and complex, driving greater demand for skilled labor,” indicated a 2014 Milken Institute report. In the Greater Sacramento region, where Woodland is located, an estimated 5,300 new openings in positions related to agriculture will become available between 2015 and 2020 through job growth and replacing current workers, according to a forecast produced by Centers of Excellence, a labor market research provider for California’s 115 community colleges. Many of those jobs pay well and require postsecondary education, like plant scientists, industrial machinery mechanics and market research analysts.

National forecasts of the growth in agricultural workers are mixed. The number of farmers, ranchers and other agricultural managers is expected to remain mostly flat at around 1.02 million workers by 2026. Positions for agricultural and food science workers are expected to grow 7 percent by 2026 to 46,000 workers from 43,000. Employment for agricultural and food science technicians is projected to rise 6 percent to 29,200 from 27,500.

California joined the P-TECH fray by legislative edict last year. Lawmakers and then-Gov. Jerry Brown allocated $10 million to the state’s community college system for a pilot run called the STEM Pathways Academy Grant. Out of 14 applicants, six partnerships prevailed for the five-year grant, each one requesting funding at about $1.4 million. The colleges will focus on one or two career pathways in agricultural science and technology, cybersecurity, biotechnology, manufacturing, information technology or nursing. That’s according to a review of grant applications that The 74 requested from officials at the California Community Colleges.

Unlike the Brooklyn version and its counterparts, California’s model will offer free college courses only while students are still in high school, said Raul Arambula, dean of intersegmental support at the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office. Students will have to pay the standard $46 per unit at community colleges once they graduate from high school to continue in the program, despite “a rigorous, relevant and cost-free education in grades 9 to 14” being a stated goal of the pilot. Nearly half of the state’s community college students are low-income students who receive state tuition waivers, which offset the tuition costs. Full-time students can further receive financial relief through local promise programs that offer free tuition.

The California experiment seeks to instill a college-going culture in communities where degree attainment lags and draw stronger ties between businesses, high schools and community colleges so that students graduate with employable skills. The pilots will start small, each enrolling several dozen or fewer students per year. Woodland plans to add 30 students a year for the five-year duration of the pilot. In West Contra Costa, a more urban area closer to San Francisco, 60 to 80 students are expected to enter the manufacturing and information technology programs each year. Like other programs in the pilot, the West Contra Costa Community College District plans to heavily recruit students in households where no adults completed college.

San Diego Miramar College, another pilot site, plans to enroll about 100 students in total for its biotechnology program. The region it serves expects 1,509 openings in biotechnology jobs between 2016 and 2021 that require college awards but not a four-year degree.

As this is the planning year in Woodland, the community college has yet to hash out many of the program’s details. How many college units will students take while they’re in high school, how will students be selected for the program and what their first college classes will be are still in the works, Iatridis said.

The college wrote in its grant application that it wants at least 70 percent of its students to earn an associate’s degree after six years in the program. Students will have access to college tutoring for their college-level courses. Woodland will also be keeping track of student success in the program by collecting data on transfers, completion and employment, Iatridis said.

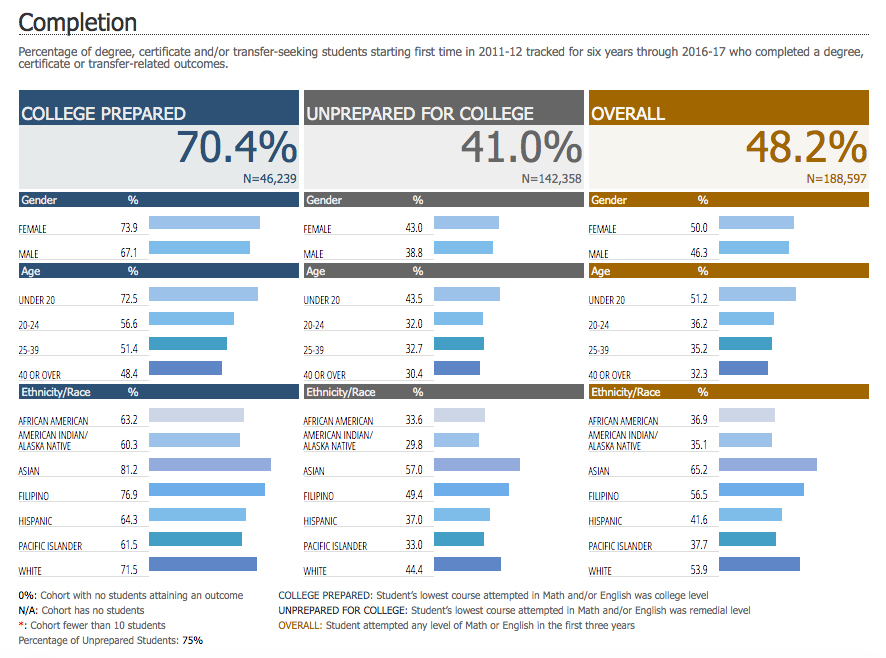

The goal of ensuring that students graduate on time from community colleges has spawned numerous reform efforts in California. Just under half of students earn a certificate or transfer to a four-year university after six years of community college, system data show.

West Hills Community College District, another winning applicant and one focusing on agricultural technology, wants students in its program to be earning 30 college units by the time they finish high school — half the units needed for an associate’s degree. That could go a long way toward increasing the odds that students earn associate’s degrees or transfer on time.

Students in ninth grade will start their college sequence with a course in tractor operations and another on college success. The 10th-grade college curriculum will include a world history course and computer applications for agriculture. Juniors and seniors will take college courses such as introduction to agricultural economics and introduction to plant science, along with courses in elementary Spanish and art appreciation.

“These are college courses, they just happen to be at the high school,” Arambula said.

The businesses of agriculture and viniculture loom large in the counties near Sacramento that Woodland College services.

Expanding degree offerings and transferable courses in those sectors was one of the college’s main objectives.

“When we think about food and agriculture right now, there’s a definite shortage of labor. It’s definitely a time of tremendous evolution in food and agriculture,” Purcell said. Bayer is still finalizing its plans with the college, but Purcell noted that the Bayer-Woodland partnership is a “great way to really provide the kind of pipeline of talent that we need for an industry that’s evolving rapidly.”

And though California has launched several efforts to expose more high school students to college courses, like dual-enrollment programs and early colleges that allow students to earn college credit through nearby community colleges while still in high school, the STEM Pathways Grant stands out for its emphasis on job preparation.

Business partners are “not simply an advisory board, they play a huge role in the delivery of the curriculum over the four years,” said Michael White, who retired as Woodland Community College president June 30. Bayer’s Purcell is helping the college attract other business partners to expand the breadth of the program.

Students aren’t obligated to choose work over college once they complete the high school or community college leg of the program. Courses offered will allow students to transfer into four-year universities if that’s the path they choose.

“There would be a natural pipeline to UC Davis for those who want to pursue a bachelor’s or any other higher degree,” White said.

But like the other pilots in California, the partnership between Woodland and Bayer will come with internships and other job-training elements for students of the program, including a placement at the front of the line for job interviews.

That investment makes sense for the company.

“We’re always looking for a pipeline of potential employees,” Purcell said. “And I think what’s cool is, when kids come through programs like this, they have an advantage, frankly, because there’s already been an exposure with either us or other companies in the field.”

Disclosure: The 74’s coverage of the skills gap, the challenges and opportunities of better educating our future workforce, and efforts underway to improve local employment pipelines is underwritten in part by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)