In a Disastrous Year, States That Mandate FAFSA Completion Fared a Bit Better

Mandatory states’ existing support infrastructure may have insulated them — and their students — during the messy rollout.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated, April 25

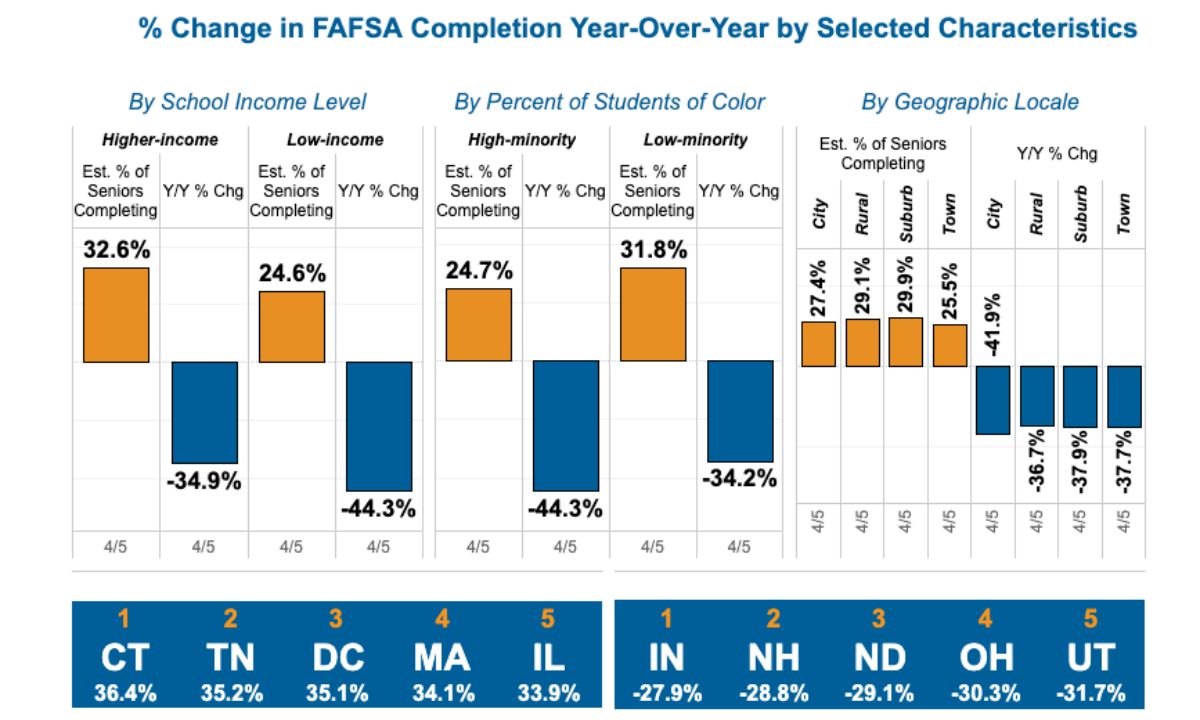

While applications for federal student aid dropped by double digits across all 50 states this year, those with universal FAFSA completion policies seemed to fare slightly better, with the majority performing in the top half of the country.

Of the 10 states with the highest completion rates, three — Louisiana, Illinois and New Hampshire — have mandatory FAFSA policies for high school seniors. Across all states, Connecticut had the highest completion rate among high school seniors and Alaska had the lowest, according to the National College Attainment Network.

Indiana saw the smallest change year-over-year in its completion rate and Tennessee had the greatest year-over-year swing, with a 44.3% drop — though it still had the second-highest completion rate in the country. Typically, the stronger states were last year, the further they fell this year, according to the network.

Experts attribute this relative success to the mandatory states having supportive infrastructure that provided students with the tools they needed to navigate the submission process in what has turned into a notoriously problem-ridden year.

But no state has emerged from the process unscathed.

“While there is certainly some variation across the states, the pattern holds,” said Katharine Meyer, fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Brown Center of Education Policy. “Where submissions are down, completions are down. There are large gaps between the high-income and low-income high schools and then it’s just the magnitude to which those play out in different states.”

This year marked the release of the new form following the FAFSA Simplification Act, which was meant to streamline and simplify the historically complicated application for federal student aid, expand access to Federal Pell Grants for low-income students and change the way expected family contribution is calculated. But a botched rollout marred by delays and technical glitches — particularly for students whose parents are undocumented and don’t have Social Security numbers — has led to a dramatic drop in the number of students who have been able to submit the form. That’s left seniors in a lurch and both high schools and colleges scrambling.

Not all students have been impacted equally, though. Among those at higher-income schools — where fewer than half of students qualify for free or reduced-priced lunch — about 36% completed the FAFSA this year, while only about a quarter of students at lower-income schools have, according to the college attainment network. The year-over-year drop is also significantly higher for students at low-income schools with an almost 10-point difference.

“It’s the lowest-income students, the first-generation students, who don’t have additional resources to guide them through this process, who are ultimately paying the price for this rollout,” said Meyer, “which is awful because the entire goal of the FAFSA Simplification Act was to target and support those students and make this an easier process.”

While there have always been gaps between students who have extra support and those who don’t, the added complexities and “minefields to navigate” on this year’s form exacerbated them, she added.

Overall, there’s been a 24% drop in the number of forms submitted as compared to the same time last year, according to The 74’s analysis of U.S. Department of Education data, and a 38% drop in the number of forms that have been completed without errors, according to the college attainment network, whose members include school districts and nonprofits.

As of April 9, 16% of FAFSA applications still needed student corrections and about 30% of forms were potentially impacted by processing or data errors, according to a report released by the U.S. Department of Education.

The completion rates are of particular significance, according to Bill DeBaun, the network’s senior director of data and strategic initiatives.

“Completions remain the target for NCAN and our members, and it’s what we’re encouraging the field to pursue,” he wrote to The 74. “Having a college-intending student who was motivated enough to submit the FAFSA, but who did not connect with financial aid because of an error that they didn’t correct, is a tragic outcome.”

Sheri Crigger, a college counselor at the School of Cyber Technology and Engineering in Huntsville, Alabama, said the biggest challenge is for students who still don’t have FAFSA results or aid packages from schools, even as the traditional May 1 decision day deadline quickly approaches. Normally by now, she said, kids would be announcing where they’re headed in the fall and wearing their new schools’ colors. Instead, she said, there’s just a feeling of uncertainty.

“I feel for them because there’s not a fix for that until they have the information they need,” she said. “I like to be able to kind of point them in a direction [but this year] there is no direction.”

Changing the mindset from optional to required

Nationally, seven states — Illinois, California, Louisiana, Alabama, Texas, Indiana and New Hampshire — have implemented universal FAFSA policies and five additional ones — Connecticut, New Jersey, Kansas, Nebraska and Oklahoma — have passed them, according to the network. Louisiana, which was the first state to implement a universal FAFSA policy in 2018, became the first to roll theirs back this year. State lawmakers said they were reversing course for a range of reasons, including arguments that the policy prioritized college over trade schools — although federal aid can often be used for the latter — and that completion is a burdensome requirement for families.

Elizabeth Morgan, the attainment network’s chief external relations officer, disagreed with their line of thinking.

“Universal FAFSA is not about penalizing students or holding students back,” she said. “It’s about changing the mindset from optional to required.”

Students — especially those from lower-income backgrounds — don’t always realize that financial aid is available to them until they submit their FAFSA form, Morgan added. They also might not know that the aid can be used at institutions other than four-year universities, such as trade schools and community colleges. Filling out FAFSA, she said, is important for these students because it fixes these misconceptions.

In states where there are mandates or universal FAFSA rules, schools are more likely to integrate support for completion into the school day and create more of a culture around it, leading to a significant increase in filing, according to Meyer, the Brookings fellow. Events such as FAFSA drives can also help to boost completion rates in a typical year by providing families with the tools they need to navigate the cumbersome, complex process.

When looking at the list of top submitters this year, a lot of them are states that have these mandates in place, Meyer said, suggesting that universal policies may have helped insulate them — and their students — during the messy rollout.

“They still aren’t good FAFSA submission and completion numbers… but it is less bad than in some other states,” she said.

Some experts in the field remain anxious that this will be an ongoing issue in future years. Meyer warned that there are already signs that next year’s form won’t be released on time once again. If the form is delayed but not riddled with errors, she added, students may still avoid this year’s chaos, especially since institutions are staffing up in anticipation.

“I do think long term I am an optimist,” she said. “I’m hopeful that this act will ultimately increase college access for those students, but it’s a bumpy couple of years in the process.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)