‘Bungled’ Financial Aid Rollout Leaves Graduating Seniors in Limbo

While the Education Department is helping colleges process forms amid delays, advocates want more help for K-12.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

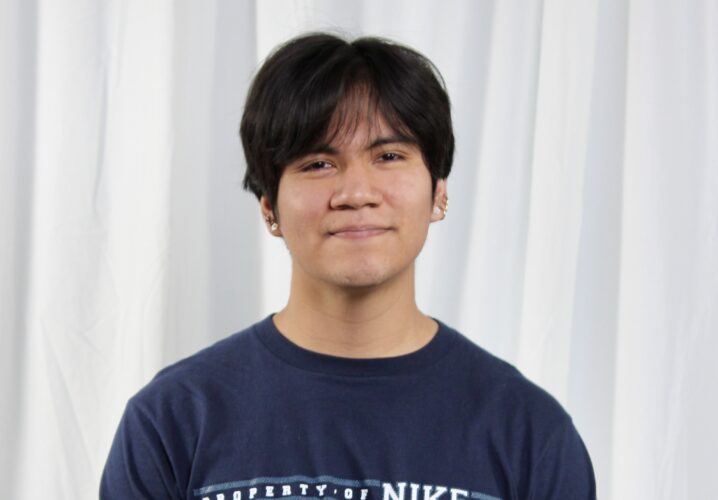

Jose Martinez, a senior at Senn High School in Chicago, wants to teach someday — maybe English. He’s applied to several top colleges in Illinois, but for now, he’s in limbo, unable to complete the financial aid forms he’ll need to attend.

A newly-revamped online application requires at least one parent to independently log in and sign the form. But the system wouldn’t verify his father’s Social Security number. When his mother tried, “it just gave us an error message,” he said.

Those are among the snags that thousands of students are experiencing due to delays with the rollout of the new FAFSA, or Free Application for Federal Student Aid. The U.S. Department of Education overhauled the form last year for the first time since the mid-1980s. The changes were supposed to simplify the process and make more low-income students eligible for aid, but students now face a time crunch. Many have already received college admission offers, but don’t know how much financial aid they could receive. Others haven’t been able to complete the application because of computer glitches. And some have watched the disarray and are hesitant to apply at all.

On Tuesday, the department offered a temporary solution for students like Martinez that allows parents to complete their portion of the form, but it could be March before a complete fix is available. The problems help explain why the number of students completing the FAFSA is down by roughly half from last year — and why the department is under bipartisan pressure to speed up the process,

“I fear that many of these students may not attend college this fall due to the frustration of submitting the FAFSA and the delay in receiving aid offers,” said Tam Doane, an adviser with Peak Education, a Colorado Springs nonprofit that works to improve college enrollment rates.

In recent weeks, federal officials have launched efforts to help the nation’s universities catch up with some of the four million new federal financial aid forms submitted since the new application opened in January.

They have assigned federal staff to institutions serving high-need populations and set aside $50 million for nonprofits that specialize in financial aid. But some advocates would like some of the money to go to organizations like Peak, or for the department to create another pot of funding forK-12 districts.

“We’d like to see summer support hours … and more resources to support counseling right now,” said Catherine Brown, senior director of policy and advocacy for the National College Attainment Network, whose members include school districts and nonprofits.

Federal officials say they are providing “targeted outreach” to K-12 districts and nonprofit groups and have created a website that shows administrators how many students in their high schools have completed the FAFSA. For parents, they’re holding webinars to explain the changes and answer questions, including one set for Thursday.

Carlos Jiménez, CEO of Peak Education, isn’t surprised by students’ low completion rates.

“They’re like, ‘[The application] just opened, and I’ve got some time,’ or ‘It’s a mess, so I’m going to wait a little bit longer to figure it out,’ ” he said. “Hearing about how it’s been bungled adds a layer of anxiety.”

‘A broken system’

The changes that are overwhelming the system are the result of a 2020 law that streamlined the application. It now includes fewer questions and is intended to make more low-income students eligible for the maximum Pell Grant amount. But the form is usually available in October — not January — and the department said it won’t begin sending FAFSA information to colleges until mid-March, giving students less time to make decisions.

Advocates and members of Congress fear the delays are harming students that the revisions were supposed to help the most.

Republicans called the implementation “botched” and asked the Government Accountability Office, a watchdog agency, to investigate.

The situation has also roused the ire of Congressional Democrats, who last week asked Education Secretary Miguel Cardona to ensure that low-income students most in need of financial aid won’t be further harmed by these delays.

Cardona, in a call with reporters earlier this month, said the work is complex.

“We’re completely overhauling a broken system,” he said. Ultimately, he added, the new process will be “transformational.” “When we make FAFSA simpler and easier, we make the decision to pursue higher education simpler and easier.”

Those aren’t the words Priya Linson would use to describe this year’s process.

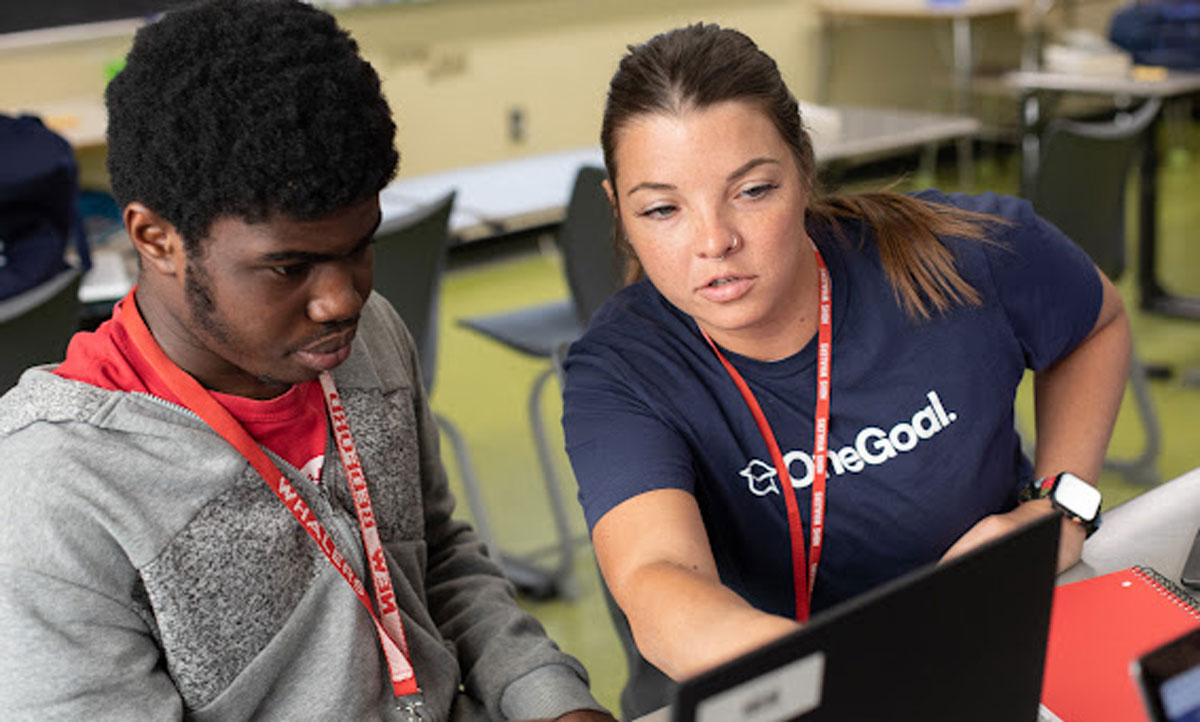

“Students have reported that their family is sitting on a helpline for hours until it literally times out and they get disconnected,” said Linson, executive director of OneGoal Chicago, a nonprofit helping students like Martinez prepare for college. “That’s the kind of experience that is pushing students to wait or potentially just question if this is even the right decision.”

Students whose parents are noncitizens have been most affected. Without Social Security numbers, they can still submit a paper form, but that just creates more delays, Jiménez said.

“If you have ever sent a paper form to the government, you know that’s going to be a four-to-six-week process,” he said. “That’s a real disadvantage if you’re trying to make a decision on where you’re going to college.”

At two high schools, Peak runs “blitz sessions” in the computer lab every Wednesday to help students create the usernames and passwords needed to complete the form. Doane, the Peak adviser, gets students to take out their phones and locate the most recent FAFSA messages.

In some cases, she said, once a parent electronically signs the online form, the student’s signature is removed and they can’t make corrections.

“It will be months — and additional work — before they know what federal aid they may be eligible for,” she said. Some students, she added, might miss out on scholarships as well.

In Illinois, counselors have asked administrators to fund summer hours to help students after they receive financial aid offers, said Vince Walsh-Rock, executive director of the Illinois School Counselor Association.

But Jiménez, with Peak, said organizations already set to work over the summer need additional funding to help more students.

“You’re asking [counselors] to either volunteer or get extra hours if you have some money,” he said. “Maybe they would do that, but maybe it’s, ‘Hey, it’s been a tough year. I care about my kids, but I’m out.'”

Higher education organizations have asked colleges to push their enrollment deadlines past the traditional May 1 “decision day” so families have more time to consider financial aid offers. Some university systems have already adjusted their timelines.

But delaying some deadlines, Linson said, doesn’t mean schools will be flexible about tuition deposits, housing arrangements and “all of the other things that pile up once a student gets admitted.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)