Improving Math Proficiency Starts With Us, the Educators

Barasch: Teachers and school leaders need to stop resisting new approaches to math that can help students master the subject.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

“Well, that’s not how I learned it,” proclaimed the person sitting next to me.

The comment is a familiar one for a math teacher, as I hear it all the time from students and family members. But on this particular day, the source of the remark surprised me: I was at my school’s professional learning committee meeting, and the speaker was one of my long-tenured math teaching colleagues.

“I can’t learn new ways to teach this material, it would take so much work,” he added.

“Isn’t that the job?” I thought.

As a sixteen-year veteran of teaching high school math in Texas — everything from Pre-Algebra to AP Calculus — I am wary of curricular and pedagogical overhauls. I’m skeptical of anything that claims to “reinvent” math instruction, since it is unlikely that some guru will come along for the first time in history with a silver bullet that instantly causes all my students to learn math flawlessly.

But the opposite approach is more insidious. How presumptuous would it be to assume that teaching and learning cannot evolve, especially in this modern era of emerging technologies, artificial intelligence, and external factors like a pandemic and record globalization?

If teachers are to be treated — and paid — like other professionals, educators like me must act like them. For example, physicians here in Texas must renew their licenses every two years, including 48 credits of continuing medical education. For attorneys, it’s every five years with 105 hours of continuing legal education.

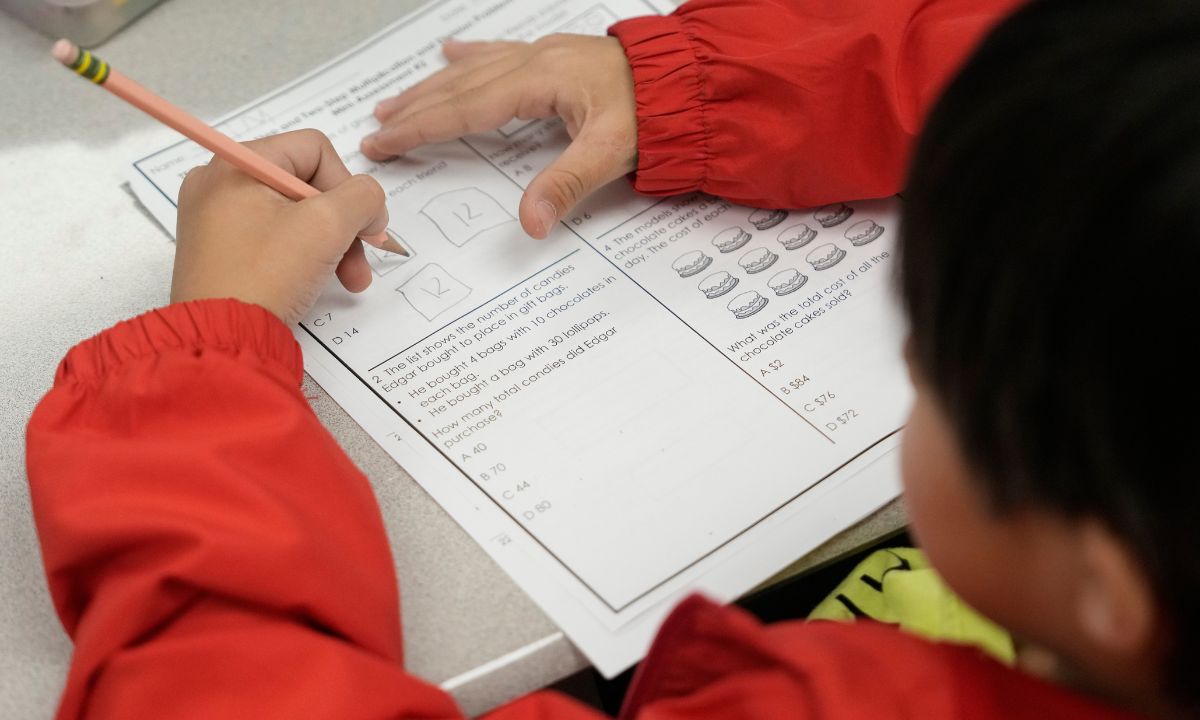

As a contrast, in my profession, many teachers are flat-out resistant to new techniques, often falling back on old-fashioned strategies and worksheets even while national standards like Advanced Placement update their exams nearly every year. In the worst instances I have witnessed in my career, I have seen dated, stale “plug and play” photocopies circulating in the staff workroom, often being frantically printed on the morning of delivery. How are teachers refining their instruction if they’re not even updating the date on the worksheet?

And here’s the rub: The old strategies aren’t necessarily working. We should be very concerned about the latest Nation’s Report Card in mathematics, which shows American students falling well short of expectations over the past decade relative to the rest of the world. Some reports of this decline date back to before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Math proficiency is vital for all our students to be successful. The learning of math is a fair predictor of overall academic achievement, along with college readiness and even future earnings. Math teachers must step up to the challenge and prove ourselves to be on the vanguard of innovating math instruction, teaching students in the ways that 21st-century students learn.

Schools need to invest in math literacy as a core infrastructure for learning, focusing on math with the same zeal they take on reading.

For starters, around 48% of schools have reading interventionists, yet less than half of that figure (23%) have the equivalent for math. The schools that do not often rely on teachers meeting during non-instructional time, sometimes shepherded by administrators without expertise in the important and effective skill of organized tracking of students based on evidence.

At the school and district level, coordinators and instructional specialists need to be unafraid of research-supported innovations for kids to learn, especially approaches that are responsive to the current technological climate. In my district, we have adopted robust new curricula with extensive resources for teachers old and new and also hired consultants to work with teachers directly in their classrooms.

There is no shortage of innovative and learnable EdTech available to districts, much of which allows students to explore math problems independently on their personal devices, while receiving immediate feedback. We just need to actively push and support teachers to implement them.

For specialists working with teachers like my dubious colleague, there are plenty of strategies for coaches to combat resistance to change. In 1986, when the National Council of Mathematics recommended the use of calculators in school, a group of teachers picketed with concern that this would leave “students with no reason to learn computational skills.” Yet now the calculator is one of many foundational tools that can aid math learning. Let’s not be on the wrong side of the picket line with the future of technology.

As for the way we talk about math writ large, the science of reading movement has been so effective in changing hearts and minds, and it’s time for math to have its own moment. Effective math instruction is not an impossible dragon to slay.

This is decidedly not the time to continue falling back on “how we learned it when we were kids.” We educators can and should be the ones who make math instruction and intervention more effective. The problem of math proficiency among American students is one we can absolutely, collectively solve. Let’s do better right now for our students in order to improve scores nationwide, so that our students are most prepared to solve the problems of their futures on the global stage.

For me and my fellow educators to shirk the opportunity to investigate new and best practices for our students would be tantamount to malpractice.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)