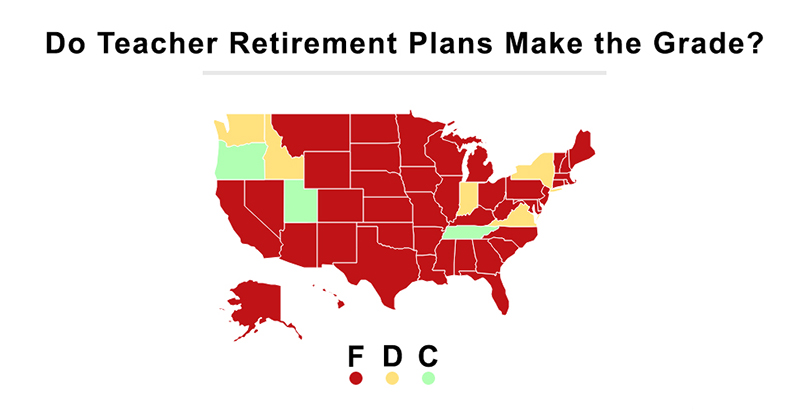

How States Fail Their Teachers on Retirement: New Report Gives 42 States Failing Grades for Pensions

The vast majority of states are failing teachers when it comes to their retirement, according to a new analysis.

A report out today by Bellwether Education Partners grades teacher pension plans on an A–F scale, giving 42 of the 50 states and the District of Columbia an F for their educator retirement systems. No state scored higher than a C: Utah, Oregon, and Tennessee lead the pack with the average letter grade. Alaska, Virginia, Washington, Indiana, Idaho, and New York barely pass with Ds.

Bellwether’s Chad Aldeman and Kirsten Schmitz rate states not on specific policy choices but on how well each caters to its unique workforce. The metrics they use are based on two fundamental questions: “Are all of the state’s teachers earning sufficient retirement benefits?” and “Can teachers take their retirement benefits with them no matter where life takes them?” A state would earn a perfect score if it offered all its educators “a portable and financially secure retirement plan.”

(Visit TeacherPensions.org for an interactive map of the grades and more details on each state.)

“Current teacher retirement systems are often designed in ways that systematically disadvantage young and mobile teachers and impair the ability of schools to recruit, hire, retain, and compensate high-quality teachers,” Aldeman and Schmitz write. “What we found is a mostly depressing picture: States have set up expensive, debt-ridden retirement systems where most teachers fail to qualify for decent retirement benefits.”

For decades, educators have theoretically been enticed by the promise of generous benefits at the end of their careers, particularly in the face of low salaries during their working years. A cornerstone of educator compensation packages, teacher pensions cost states and districts more than $50 billion a year. But recent studies are suggesting that the light at the end of the tunnel might not be so bright after all: American teachers on average have to wait 25 years before their pensions are worth more than the initial investment, according to a paper from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. And a separate Bellwether analysis estimates that half of new teachers won’t qualify for a pension at all.

“Not just for teachers, across the board we’re in a mobile generation. There are many circumstances why any employee may move to a different state or a different job,” Schmitz told The 74. “Teachers think, ‘I’m saving towards a pension fund and that money is going to be there for me,’ but the majority of teachers will not benefit from the current system, and that doesn’t seem right. Right now there’s a small group of winners and a very large group of losers. I don’t think many people know that.”

There are two major types of pensions: defined contribution plans — like 401(k)s — and defined benefit plans — like Social Security. Many states and districts use some combination of the two. In a defined contribution plan, an employee, employer, or both contribute to the employee’s retirement plan. The payout upon retirement depends on the returns on the investments that are selected, and the plan can move with the employee from state to state. Payouts are not guaranteed by the government. A defined benefit plan, however, guarantees automatic payouts based on a formula that incorporates an employee’s salary and years of service. Employees and employers contribute regularly to the fund, teachers lose the employer contribution if they quit too early, and they generally cannot carry the full value of their pensions with them to another state.

To grade state pension plans, the authors considered the following variables:

- The percentage of teacher salaries going toward retirement

- The percentage of teacher salaries going toward pension debt

- The percentage of teachers who qualify for employer-provided benefits

- The percentage of teachers who earn retirement savings worth at least their own contributions plus interest

- The percentage of teachers covered by Social Security

- Whether a portable retirement savings option exists

About 40 percent of K-12 teachers — more than 1 million — are not covered by Social Security. An average 28 percent of teachers across the country will at least break even on their retirement plans, according to the results released today. Alaska tops the list, with a full 100 percent of teachers expected to reap retirement savings worth at least their own investment plus interest, while Massachusetts lands at the bottom, with no new teachers expected to break even, ever.

Methods to improve will vary across state lines, but Aldeman and Schmitz offer the following recommendations that they say should govern all states’ action items:

- Get finances under control

- Make portable teacher retirement plans the default to provide all teachers with financially secure benefits

- Expand Social Security coverage to include teachers.

“Without dramatic reforms, [states will] continue to fail teachers and leave in place unfair, unsound retirement systems,” the authors write.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)