Teachers Have to Wait 25 Years to See Pension Benefits, New Study Says, But Is the Fix Really Better?

The idea is that this attracts people to the profession, knowing a secure retirement awaits, and gets them to stay long enough to collect on it.

But a number of reports have questioned that line of thinking, arguing that backloaded pensions are unfair to newer, short-time and more mobile teachers and fails as an effective means of compensation.

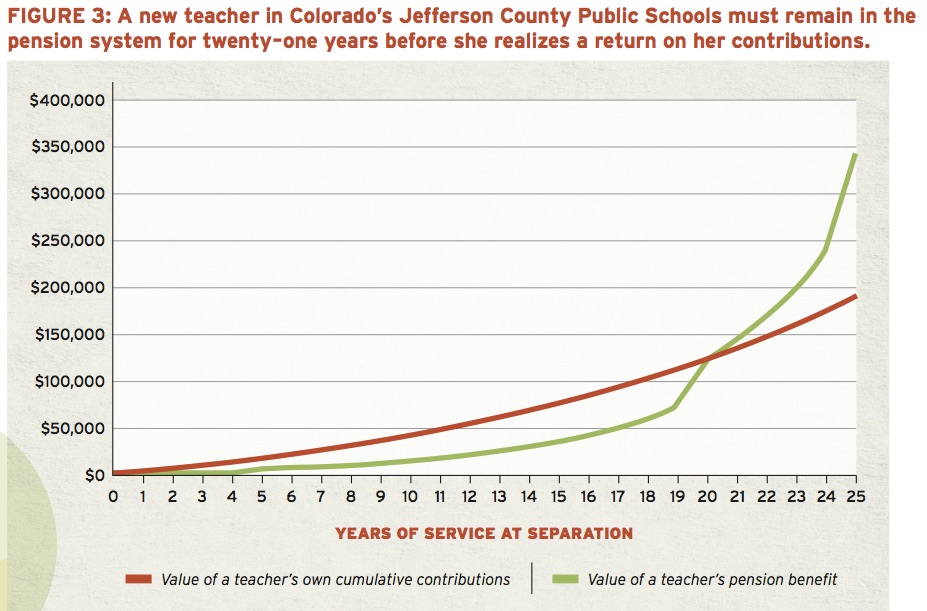

A new paper from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a conservative education think tank, is the latest, arguing that teachers are getting a raw retirement deal. The Fordham research looked at the teacher retirement systems in the largest school districts in all 50 states and the District of Columbia and found that teachers have to wait an average of 25 years before the value of their pensions are larger than what they contribute themselves.

“Newly hired teachers in the majority of districts will be covered by retirement plans designed so that they will contribute more to retirement than the value of their benefits — for nearly an entire career,” the study states.

The report advocates letting teachers choose between traditional pension programs and a 401(k)-style system.

Although the study at points overstates the extent to which some teachers are disadvantaged by prevailing retirement systems, it raises important points about whether pensions are an effective means for recruiting and keeping teachers.

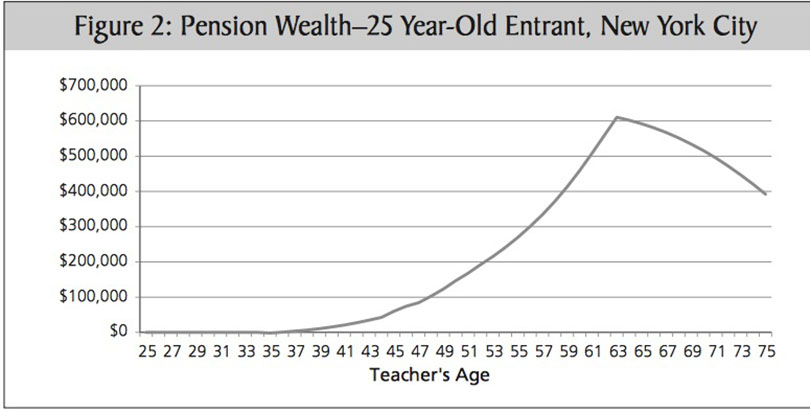

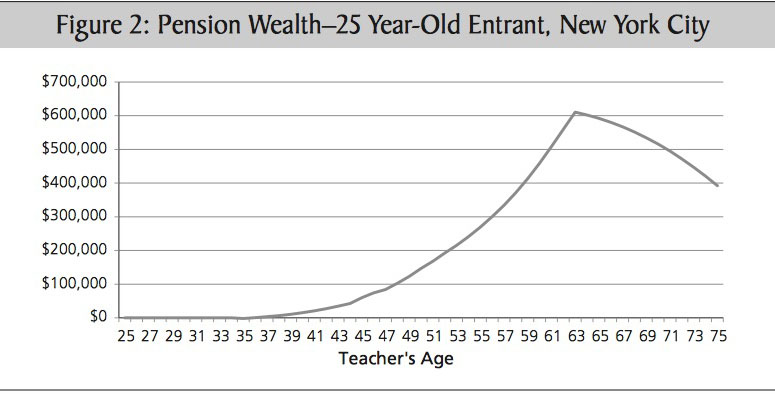

These programs are heavily back-loaded, meaning that teachers retain most of the value of such a system late in their careers. (See, for example, the structure of New York City’s system below.) Teachers usually cannot take the full value of their pensions with them if they move to another state. Teachers who quit too early to benefit can get a refund of what they contributed but usually not of the employer contribution.

Defined-contribution systems, like 401(k)s, create an individualized retirement account, in which a teacher’s retirement benefit is simply the total contributions from the teacher and the employer, as well as any interest from investments. These benefits accrue slowly over time and can move with the teacher between states. Upon retirement, the benefit lasts only as long as the money saved and the accrued interest holds out and is not guaranteed by the government.

A number of states and districts use a combination of both systems.

Teachers heavily rely on these systems in order to retire, particularly the 40 percent who are not covered by Social Security.

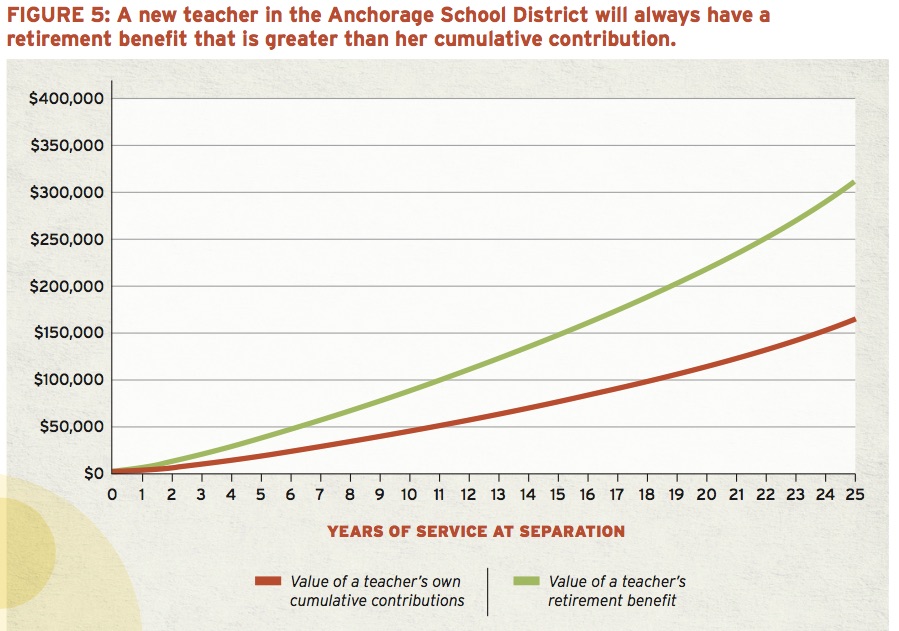

The Fordham paper calls the juncture at which teachers’ retirement benefits are worth more than their own contributions the “crossover point.” Under most teacher pension systems, this doesn’t happen for decades, almost always more than 20 years, in some cases 30. In Boston, Chicago and Anoka-Hennepin County (Minnesota), teachers never cross over.

“Since the average experience of a teacher who leaves the profession is fifteen years — and fewer than one out of four stays more than twenty years — many teachers will never see a ‘benefit,’ ” the report states.

In the six districts that offer defined-contributions programs instead of traditional pensions, the crossover occurs immediately. This is by design, as employer contributions are immediately credited to the teacher’s account.

The report uses stark language in describing these findings. “For a nation that places great emphasis on equity, it is astonishing that so many states now tacitly endorse pension systems that are inequitable to current and future generations of new teachers,” study author Martin Lueken writes.

The paper frames the back-loaded retirement systems as amounting to “pension theft.”

“Any teacher who separates from the retirement system before the crossover in any of these districts will incur a loss on her contribution to the system when she leaves,” the report states.

But it’s not quite right that teachers actually lose money under this system, since as the study acknowledges at another point, “Of course, no matter when [a teacher] leaves she can choose to ‘cash out’ and receive a refund,” usually with interest.

Dara Zeehandelaar, research director at Fordham, said in an interview, “Our definition of a loss is [when] what you put in now is worth less than your expected benefit in the future” — in other words, the crossover point.

She acknowledged that “[teachers] can break even with a refund” but noted that many teachers may not realize that a refund is a better deal than taking a pension. Zeehandelaar said she wasn’t aware of any available data quantifying how many teachers take refunds over pensions.

The Fordham study argues that heavily back-loaded traditional pensions harm the quality of the teacher workforce by interfering with healthy turnover: “The [defined contribution] plan does not penalize mobile teachers or those who decide teaching is not for them. Nor does it incentivize veterans to stay in a system for financial reasons, even if they’re ready to leave.”

Supporters of pensions argue that lower turnover is a feature, not a bug.

Teresa Ghilarducci, a labor economist at the New School, said pension systems can be thought of as large compensation premiums for very experienced teachers that provide incentive for people to keep teaching. Since teachers generally improve over time and attrition can harm student achievement, this may benefit students.

A 401(k)-style system, simply put, gives more money to teachers who remain in the system for less time, while a pension system rewards longevity, at least up to a point.

“To give money to people who are short stayers by having a defined-contribution design may mean that you have to sacrifice the pensions of people who stay for a long time,” said Ghilarducci.

Pensions also create a strong incentive for teachers to leave after they hit retirement age, as pension wealth actually starts decreasing from there. Ghilarducci argues that this may help push out teachers who are burned out or declining in effectiveness.

Much of this assumes that teachers are cognizant of and rationally act upon changes in their retirement benefits, and the evidence is somewhat mixed on this front.

Ghilarducci points to survey data showing that teachers say they value their pensions. And this is surely true to some extent. But research finds that teachers value salary much more than retirement wealth. A study conducted after Illinois allowed teachers to pay into the system in order to receive additional benefits found that teachers were willing to pay just 20 cents on average in order to obtain a dollar’s worth of pension value. This suggests that teachers don’t value retirement benefits at nearly as much as they cost.

These results, concluded study author Maria Fitzpatrick of Cornell, “cast doubt on the ability of deferred compensation schemes to attract employees.”

This is perhaps because some teachers are poorly informed about how valuable their pensions really are.

In line with this view, Fordham recommends that districts “reduce [teacher retirement] benefit levels and increase wages.”

Cory Koedel, an economist at the University of Missouri, said that although there isn’t much research on whether pensions work as a recruitment tool, studies on retention show surprisingly small effects.

Although there is some evidence that pensions reduce early career turnover among teachers relative to similar professions — like nurses, social workers and accountants — other research shows that such retirement plans don’t seem to have a big impact on teacher retention.

“Theoretically, there’s a very strong case that pensions should increase retention” of teachers in the middle or late stages of their career, said Koedel. “But most teachers in that point of their career don’t move jobs anyway.”

Pensions do appear to lead teachers to retire at an earlier age than other professionals — social workers, nurses and accountants — but pushing effective veteran teachers to leave may be harmful. Both sides of the debate say their system is better for removing veteran teachers who may be burned out: Pension advocates say the incentives to leave after retirement age do so; skeptics say such teachers are “locked in” in the years leading up to retirement.

Studies that try to net out how the quality of the teacher workforce would change, depending on different retirement systems, come to different conclusions. Some — depending on how switches affect teacher turnover — find that traditional pensions are preferable, but others don’t.

One report examined Washington state’s switch from a defined-benefit system to a hybrid that included a 401(k)-like aspect — the change did not seem to have any effect on teacher attrition.

Other studies suggest that front-loaded salaries may be best for recruiting and retaining effective teachers.

Portability is also an issue. The Fordham study points out that pensions exact a steep penalty on teachers who move between states. Ghilarducci agrees that pensions should become more movable. Research finds that the lack of pension portability likely contributes to low teacher mobility between states, which in turn may reduce student achievement by weakening the teacher hiring pool.

The Fordham study calls for districts with a pension system to allow teachers to opt for either a defined-benefit or a defined-contribution system.

“Benefits would be tied directly to contributions and teachers would have access to employer contributions in addition to their own,” the report states. “Moreover, this would afford all teachers an opportunity to save toward a secure retirement and choose the plan that fits their own life circumstances, career goals, and preferences.”

Unmentioned are some of the issues with defined-contribution programs like 401(k)s. A recent Wall Street Journal story found that some of the creators of 401(k)s now regret that they have largely replaced pensions. Critics point to high management fees and market volatility.

“In a defined-contribution plan, the risk is borne by the individual,” said Zeehandelaar of Fordham. “In a defined-benefit plan, the risk is borne by the system or the taxpayers.”

Pension plans create a political risk of underfunding during economic downturns, as politicians may be able to ignore pension obligations in the short term, realizing that the bill will come due long after they’re out of office.

“That’s a problem, and [states] should bind themselves to full funding,” said Ghilarducci, noting that some, though not most, states have done so. Georgia, for instance, has a constitutional amendment that requires the state to fund the ongoing costs of its pensions.

Of course, the same political incentives that lead to underfunding may also deter politicians from putting in place such measures. A national study found that 10 percent of all money spent on teacher compensation is going toward older pension liabilities — that means either less money spent in classrooms for textbooks or current teacher salaries, or else higher taxes. Places like Chicago, Detroit and California have placed huge strains on schools and taxpayers for exactly that reason.

At the same time, shifting the risk onto teachers has its own downsides: For one thing, their retirements would be less secure, and for another, the value of teachers’ retirement compensation would take a hit, perhaps making the profession less desirable.

In some instances, pension critics acknowledge this: A recent blog post from the Fordham Institute argued that teachers’ pay is much higher than commonly perceived because of their “risk-free” retirement packages with high rates of return guaranteed by the government.

It’s true that the traditional pension “bargain” may be nothing of the sort for many teachers or the public, and research suggests that teachers don’t react to pension incentives in the way advocates may have hoped But how teachers would respond to a shifting of risk through a 401(k)-style approach remains something of an open question.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)