How Early Adopter Districts Are Moving Ahead Fast With AI — and Getting It Right

New CRPE analysis finds districts in Georgia, California and Washington that prioritize artificial intelligence for the students who need it most.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Districts across the country are feeling pressure to move fast on artificial intelligence, but speed without strategy can backfire. Done right, AI has the potential to expand opportunity and tackle persistent challenges in public education. Done wrong, it risks deepening inequities and wasting precious resources that the most vulnerable students need to close opportunity gaps. Preliminary research indicates that affluent suburban school districts are about twice as likely to train their teachers to use AI as high-poverty, urban or rural districts.

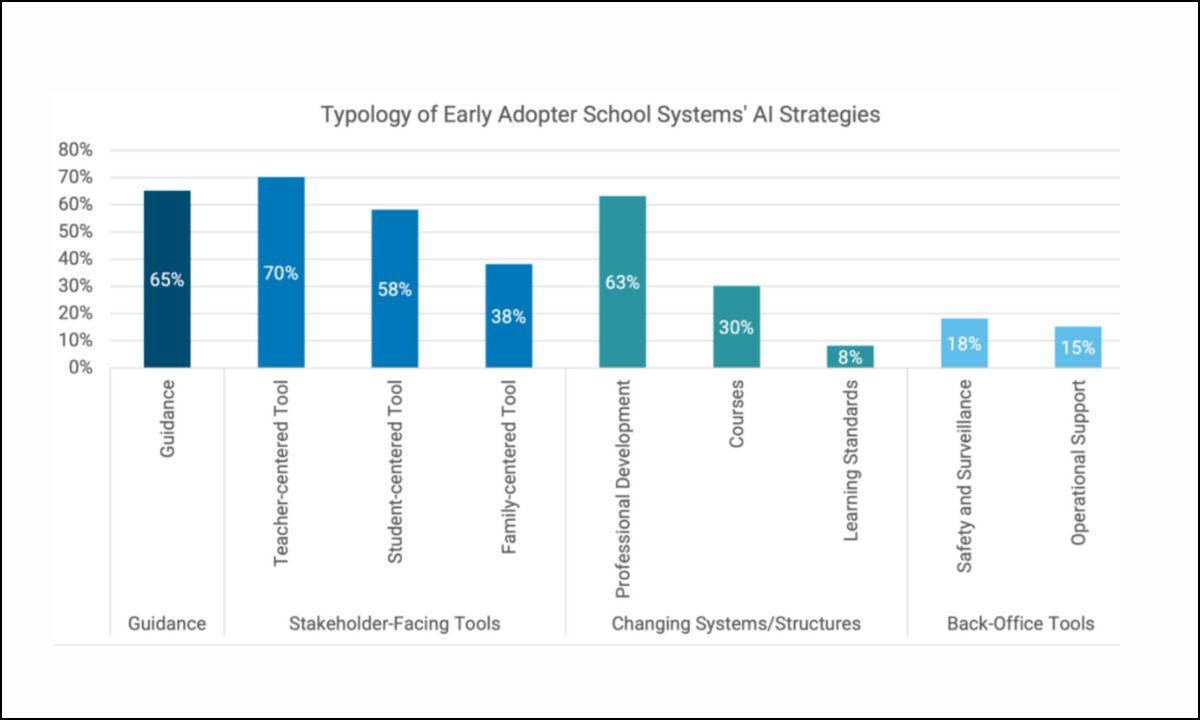

In the Center on Reinventing Public Education’s AI Early Adopter study, our researchers heard from dozens of district leaders working to strike the right balance, moving with urgency while staying grounded in equity, transparency and their core mission of educating students. According to those leaders, districts need to slow down and figure out what parents and families want in terms of preparing their children for the coming AI-based economy. They should also make sure AI efforts help marginalized students and track district progress to see if their plans are working.

This starts with understanding the risks and opportunities of AI, including dangers around bias and misinformation. Leaders must also partner with families, educators and students to learn about AI and set shared goals to make sure everyone has basic information about these tools and how they work. Districts are doing this through community conversations with their superintendents, school-based AI information sessions and task forces.

Gwinnett County Public Schools, a diverse district outside Atlanta, began broad community engagement in 2017 and learned that families prioritized future-of-work readiness. The district used this to guide conversations on AI’s role in education, consulting industry leaders and experts and ultimately creating a districtwide plan for how the technology should be used. This included new K-12 AI literacy standards, an AI-focused high school and guidance to build literacy, address bias and privacy concerns and evaluate generative artificial intelligence tools like ChatGPT.

CRPE research shows that AI adoption is most successful when carefully planned. While schools and districts ultimately decide whether students can use AI, and to what end, teachers decline to use the technology in the classroom if they don’t see how it can benefit students. This is true even though they may have access to apps and professional development. Early Adopter districts that have seen the widest use of these tools by teachers and students start by reviewing their strategic plan and identifying a specific need to address with AI-enabled strategies — such as giving multilingual learners ed tech apps that help with translation or automating lesson planning so teachers have more time to connect with students.

California’s Santa Ana Unified School District formed a task force to explore how AI can support its Future-Ready Learning framework, instructional and equity goals, and mission of multicultural readiness. The result: an AI Compass that ensures the technology is used in accordance with districtwide values, like academic integrity and student well-being. For example, the compass specifies that the district will develop an ai honor code and instruct students on how to use AI as a learning partner, rather than as a substitute for their own effort.

Alongside engaging the community and making sure AI use serves broader goals, districts can encourage safe practices by using quick, low-stakes trials that can be rolled back if they don’t work. They can test across a variety of schools to better understand the necessary and variable conditions required for successful implementation. Small-scale pilots that test different solutions and are easy to wind down to reduce risk. They also allow districts that are taking it slow to verify whether new AI tools actually reduce teacher workload or help students learn.

After all, AI won’t improve learning unless districts can track where it’s helping — and where it’s not. That means building data systems that connect tools, platforms and insights across schools, so educators can see what’s changing. Right now, too much valuable data tracking things like attendance, assessments and student interests is stored across multiple apps that can’t interact with one another. This means district leaders and educators can’t get a complete picture of how AI is helping, or hurting, students. This data is also often inaccessible to the people who need it. Without integration, AI strategies are just guesses.

Districts should have a clear data strategy grounded in making sure already disadvantaged students don’t fall further behind. Investing in AI without a plan to close gaps risks giving well-resourced students more opportunities to interact with the technology than those who are historically marginalized — reinforcing the very inequities districts hope to resolve.

Issaquah School District in Washington state employed AI to address persistent achievement gaps for students with disabilities, and those who identify as Latino or Hispanic and/or black or African American. Grounded in Universal Design for Learning strategies, Issaquah uses AI-powered ed tech tools that enable students to complete assignments in different ways, whether through voice recordings, written answers, video slideshows or other modes of expression. Issaquah is pursuing a multi-year approach to use emerging technologies to help close persistent achievement gaps through both professional development and in the selection of AI resources and tools.

Used wisely, AI can help tackle entrenched challenges like supporting multilingual learners, students with disabilities and those below grade level — but only if leaders stay laser-focused on serving those students, not chasing flashy tools. That’s why, over the next two years, EdTrust has committed to hearing what stakeholders want and need to know to ensure inclusive and fair AI use in education.

But districts shouldn’t have to do this work alone (and many can’t afford to). States and the federal government will need to play a leading role in helping districts adopt AI technologies. States should start by providing clear guidance on AI use to help districts protect student privacy and avoid unintended harm. They should also establish funding streams for AI readiness, including support for modernizing data infrastructure — ensuring all districts, not just the wealthiest, can build what they need — and hold vendors accountable for ensuring their tools do not reinforce bias or widen opportunity gaps. States and the federal government must also expand access to broadband and personal computers so that all students, regardless of geography or income, can benefit from AI-enhanced learning.

If the government and private sector can afford to invest trillions in AI-powered technology, they can invest millions to help ensure all students, not just the privileged few, are ready for a new, AI-driven future and economy.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)