How ‘Bright Spot’ Schools in D.C., Delaware Are Getting Their Students Reading

Wakelyn: Case studies — strategies that one charter school network and one district are using to make up for lost ground in K-5 literacy.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Recovery from the pandemic stalled in many schools in 2023. Upper elementary and middle schoolers lost ground in reading and math, compared with student achievement before COVID. Nationally, fourth grade reading achievement dropped to its lowest point in 52 years.

But there is promising news in pockets throughout the country. As students move through elementary school, these bright-spot districts increased reading and writing achievement at a rate double their state averages.

I’ve studied and talked in depth to leaders in two of them — DC Prep, a network of six public charter schools in Washington, D.C., and the Seaford School District, with four elementary schools in rural Delaware.

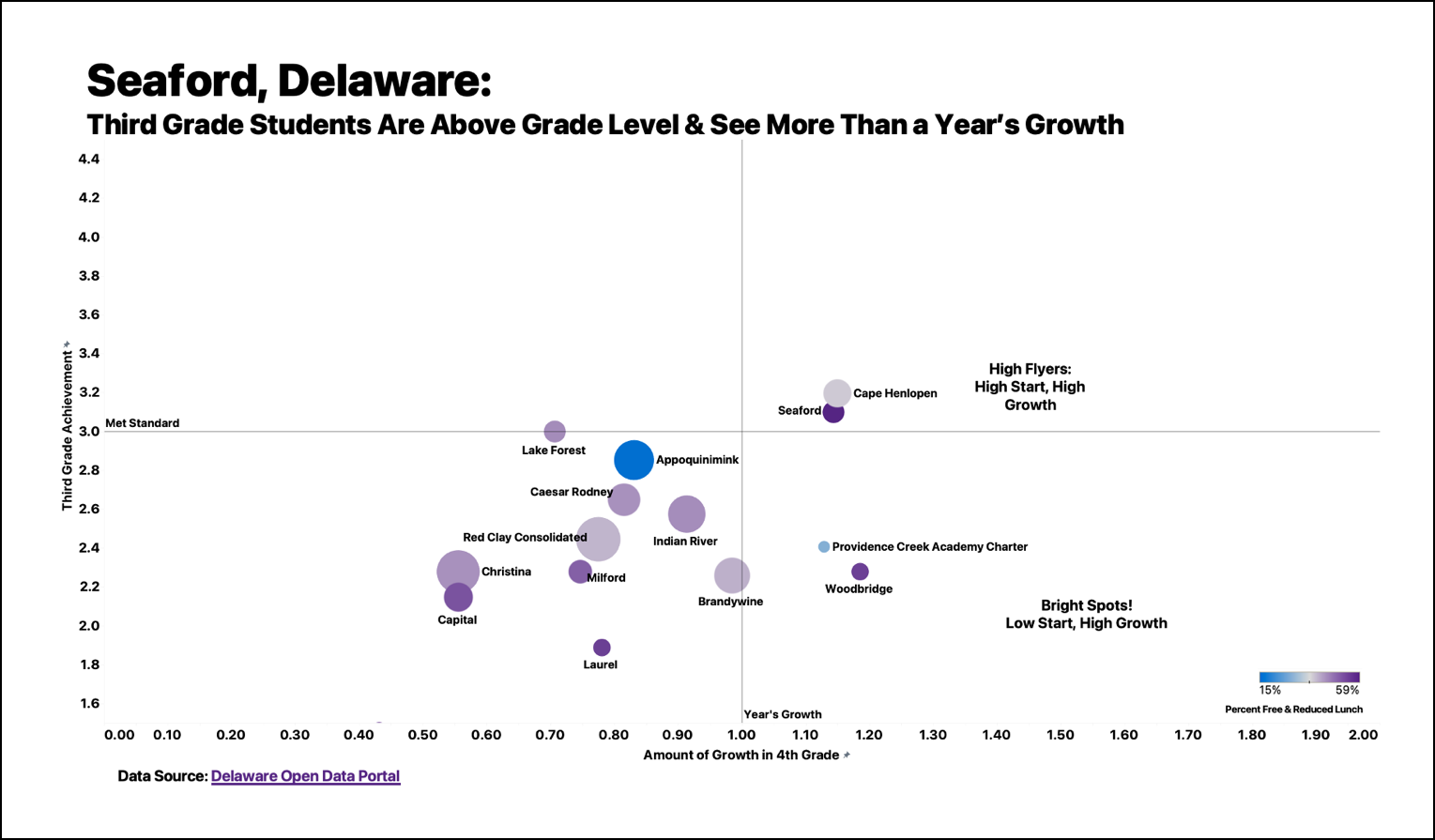

Seaford is the only high-poverty district in the state where, in 2022, students finished third grade above standards on the Smarter Balanced exam and then, as fourth graders in 2023, grew more than a full academic year.

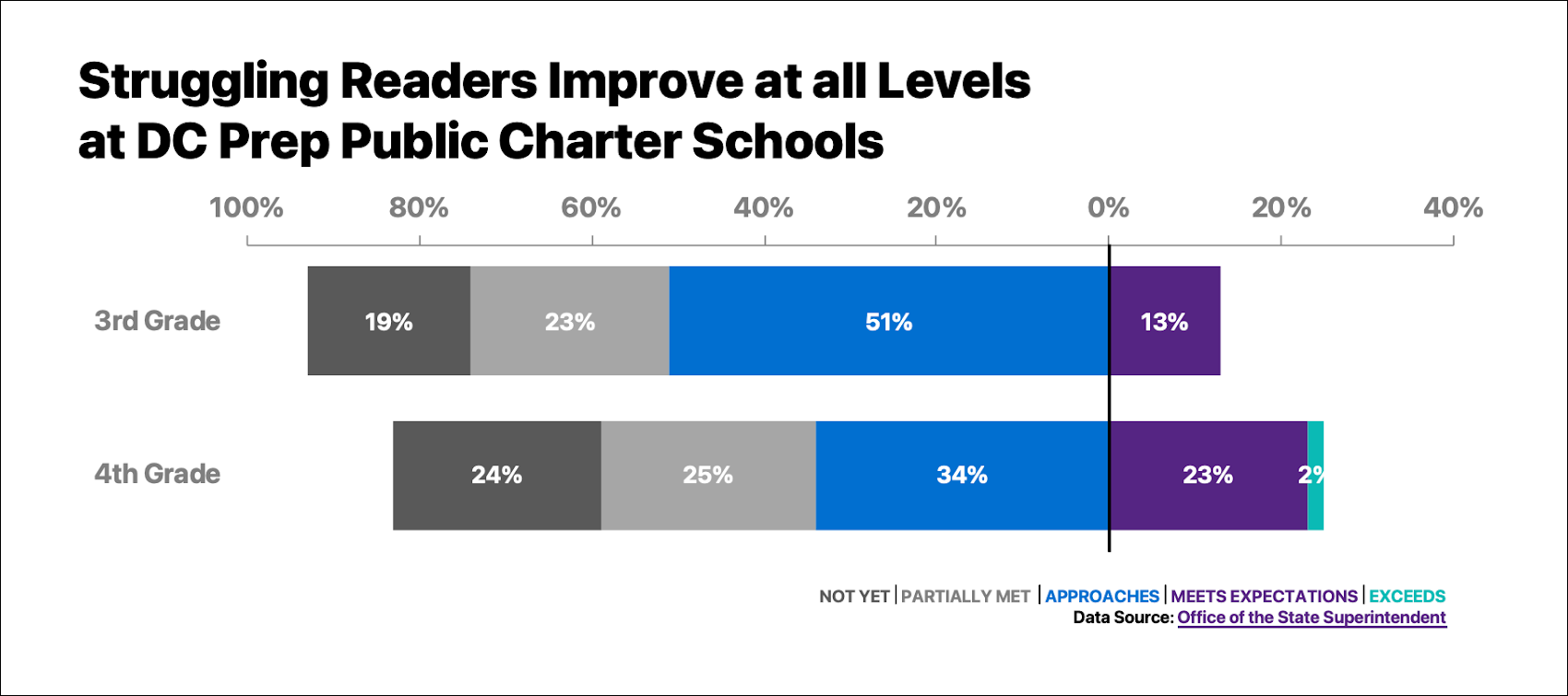

DC Prep’s students take the PARCC exam and saw growth at all achievement levels:

What sets these districts apart? Both have been influenced by the science of reading and created consistency across all aspects of teaching and learning. That is, they use high-quality curricula well matched to student assessments, and all professional learning trains teachers in how to use both well. Research by RAND finds this degree of consistency is not common in most states and districts. A large majority of teachers do not work in coherent systems.

“We’re not trying to use a silver bullet here to solve all problems,” says Mary Pendleton, director of humanities at DC Prep. “We’re focused on figuring out what works and doing it.”

Both DC Prep and Seaford combine grade-level reading and writing in one 45- to 60-minute daily block. They are adamant about teaching grade-level texts, even for students who are a year or two behind. Both districts believe this type of supportive instruction can help students move past any frustration and comprehend challenging texts.

At Seaford, teachers use the open-source curriculum Bookworms K-5, which emphasizes reading whole texts and novels rather than excerpts. To help students who might be struggling with grade-level text, a teacher and the entire class read the text aloud together, a technique known as choral reading, with a clear focus.

For example, fourth graders reading aloud from The Amazing Life of Ben Franklin are prompted to “pay attention to how Franklin got from Boston to Philadelphia.” They then reread the text, working in pairs, and are prompted to think about which parts of modern life are owed to Franklin.

Both districts use these approaches to help build students’ fluency — their ability to read accurately, at an appropriate rate, and with expression. This double dose of reading the same text is in line with the teaching recommended in the Institute for Education Sciences’ practice guide, Providing Reading Interventions for Students in Grades 4-9.

DC Prep uses an inclusion model, where special education teachers and English learner specialists co-teach with the classroom teacher. This allows them to smoothly work with small groups of students around their short-term needs, and to provide more intensive support to those who need it. For instance, in K-2, struggling readers use texts that help build specific phonics skills (e.g., “Red Ted was sad”), in addition to the grade-level text the whole class is reading.

Both districts also have a separate foundational skills block for 30 to 45 minutes each day. DC Prep had to extend this skills block, using the Heggerty series, from K-2 into third grade. They added the Fundations curriculum, as their data showed half of the students were having difficulty with phonics, up from 20% before the pandemic.

Fourth and fifth graders who need it have time dedicated to targeted phonics; those who master the basics of decoding move into studying multisyllable word patterns and have more time for independent reading. No one gets phonics skills instruction they don’t need.

Seaford has taken in new immigrants from Haiti and Central America, so it gives these students a double dose of the skills block as needed, making sure they master letter sounds and other phonics essentials. The district also goes a step further and has a third block of English Language Arts, which alternates between daily discussions of novels, and writing of narrative, informational and opinion essays. In this block, the texts are often above grade level. In each lesson, teachers stop and think aloud, demonstrating one of several strategies that excellent readers use to comprehend a text. Discussions are framed around inferential questions, where students must use clues from the text to arrive at an answer.

Both districts use assessment data to regroup students and adjust their instruction. In her book Districts That Succeed, Karin Chenoweth wrote about how Seaford does this by using improvement plans in short, 90-day cycles instead of the traditional multi-year plan.

Similarly, DC Prep uses DIBELS and ANET test data every 10 weeks to shape their priorities for the next quarter. Instructional leaders use data to frequently reconfigure small groups. For example, recent ANET data showed that some third graders who were receiving extra phonics had improved and needed to begin a new focus on close reading strategies.

This year, the school is focused on improving students’ writing. Assistant principals work with teachers to quickly analyze written responses to reading and adjust instruction for the next day. The APs also observe teachers, do real-time coaching and lead planning meetings with each grade level once a week.

This consistency around curriculum, assessment and instruction has contributed to success, but neither district is satisfied with its students’ growth. They know they have too many who are not yet meeting grade-level expectations.

This need for even greater progress suggests a new direction for educators to consider. Rigorous research has determined which programs or approaches work on average, and that data has informed these districts’ efforts. But insight about how individual students improve does not exist.

New case study research could be useful, comparing students in the same grade and district who improve to those who don’t. Generating this knowledge would provide teachers with the strategies they need to help more young people thrive as readers.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)