History Has Its Eyes on Them: Musical-Infused ‘Hamilton’ Education Program Brings Civics to Life for HS Students

Tens of thousands of American high school students each year flock to the National Mall to look up at the larger-than-life monuments to the Founding Fathers: the 554-foot Washington obelisk and the 80,000-square-foot temple to Jefferson on the shores of the Potomac tidal basin.

Few, if any, see the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it statue of Alexander Hamilton that stares out from the south patio of the U.S. Treasury Building.

For two days in September, however, more than 4,000 students from some of the poorest high schools in the nation’s capital witnessed a monument to Hamilton that may be as enduring as anything hewn in marble or granite: Hamilton, the musical.

With the Revolutionary-era heroes played by actors of color, and scenes as arcane as the founding of a national bank told in epic rap battles, the Pulitzer-, Tony-, and Grammy-winning sensation about the “$10 Founding Father without a father” has given the life of Alexander Hamilton a new resonance. And for the students from area Title I schools, the September visit to the Kennedy Center was no mere field trip; the price of admission — in addition to $10, a symbolic Hamilton — was creating and performing an original work based on documents from the period.

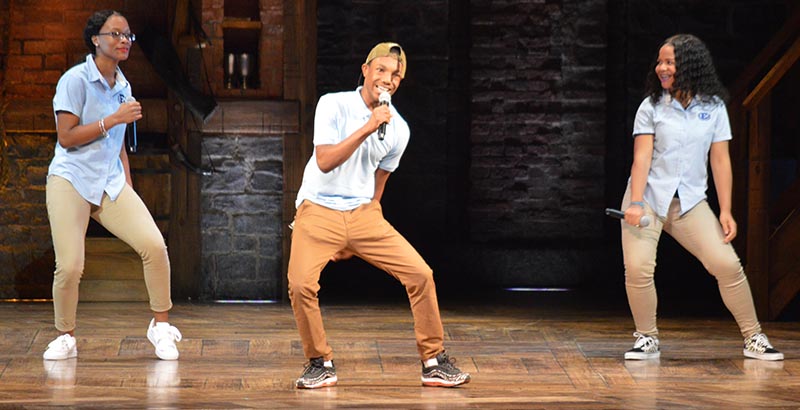

The best of these were performed in the morning, before a talkback with members of the cast and a matinee performance of the hottest theater ticket in the nation.

For Ellie Orzulak, a junior at Duke Ellington School of the Arts, the experience helped bring the era’s larger-than-life personalities down to human scale.

“Lots of times the Founding Fathers are put on a pedestal,” she said. “They’re almost untouchable, the way they’re taught in schools and textbooks.”

The spoken word and movement piece performed by Orzulak and two other students, dressed all in black, envisioned a “response to the Continental Congress.” After crediting the courage and vision of those who signed the Declaration of Independence, the trio sang the spiritual “Wade in the Water” and mimed slaves picking cotton in the fields, a reminder of the blacks and women omitted from that vision.

The musical, and the creation of their own piece, helped Orzulak see not only the greatness and ambition that fueled the likes of Hamilton and Jefferson but also their personal foibles and blind spots.

“When we wrote this, we wondered, ‘What if we stripped them down, and made them right in front of us, and talked to them not as marble busts but as people?’” she said. “What would we say?”

‘Who tells your story?’

In the haunting final minutes of Hamilton, the actors sing, “Who lives? Who dies? Who tells your story?” The answer, on this day, is the students. It’s an act of historical communion playing out throughout the country — in two touring versions and two fixed productions of the show in New York and Chicago. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, which co-created the Hamilton Education Program with the show’s producers, expects to reach 250,000 Title I students by the time the program concludes in 2020. Beyond that, the creators of EduHam, as it has become known, have nascent plans to build a do-it-yourself Hamilton program that could be used by high school teachers anywhere. It wouldn’t have the lure of a live performance by a professional cast, but organizers are mulling the idea of a national competition in which schools would send videos of their best student work, with winners sent to New York to perform and see the show on Broadway.

The musical tracks the rise of the man John Adams called “that bastard brat of a Scottish peddler” from his pivotal role in the nation’s founding to his fateful duel with Aaron Burr on the plains of Weehawken, New Jersey. Hamilton creator Lin-Manuel Miranda said he first realized the educational potential of the musical years before the show opened, when he performed what became the opening number for a White House audience in 2009. Since the video of his rendition surfaced on YouTube, it has been shown in many Advanced Placement U.S. history classes. “I think teachers used just that one clip for the past six years as their intro to Hamilton,” Miranda told Newsweek in 2016.

That’s when EduHam began. Three years on, the program is greeting students at a unique historical moment: the era of “fake news,” when understanding of U.S. history and belief in our institutions are at a low point. A recently released Gallup poll shows that 75 percent of public school superintendents find that preparing students to become citizens is a challenge — a remarkable 24-point leap from last year. In 2014, the last time the National Assessment of Educational Progress measured student knowledge of U.S. history, only 1 in 10 students demonstrated proficiency.

Judging from the reaction of teachers, EduHam may help put a dent in those numbers. According to an internal Gilder Lehrman survey, 99 percent of teachers said several months after their participation that the experience would have a lasting impact on their students, and 80 percent said the program changed the way they think about teaching American history.

Asked whether Miranda had done more for civics education than anyone else in the past 50 years, Tim Bailey, the institute’s education director, interjected, “If possibly ever.”

James Basker, the institute’s president, took it further, calling Miranda “the Shakespeare of America.”

“Hamilton is great for civics education, but that’s because this is not a didactic play,” he said. “Lin has taken the biggest story, the founding epic, if you will, and made it compelling in a modern idiom of music and language and cultural reference, and even the physical bodies of the people dancing and playing these parts. He’s reimagined the whole thing.”

Building the curriculum

It’s easy to forget that there was a time not long ago when the notion of a hip-hop musical about the nation’s founding would have been greeted with blank stares.

Bailey counts himself among the initially unconvinced. “Our executive director came to me and said, ‘Do you think we can do something?’ And I said, ‘A musical about Hamilton? Are you kidding? What kind of idea is that?’”

Miranda and Hamilton producer Jeffrey Seller knew they wanted to get the show into schools. At the time, Ron Chernow, whose 818-page biography of Hamilton inspired the musical, was a historical consultant to the production. He served as matchmaker of sorts with Gilder Lehrman. In 2005, his Hamilton biography won an award co-sponsored by the institute, the George Washington Book Prize, for best book on the founding era.

Chernow offered Bailey some of his choice center-of-the-orchestra seats at the Public Theater, where Hamilton was doing an early off-Broadway run.

His response was immediate. “I walked out and said, ‘Yeah, I think we can do something with this,’” Bailey said.

Seller and Miranda’s father, Luis Miranda Jr., met Bailey at Gilder Lehrman’s Manhattan offices. As it happens, the notion of creating an education curriculum for Hamilton fit squarely in Bailey’s peculiar wheelhouse. A former history teacher, Bailey had also been a professional actor, with several stage and film credits to his name. He showed the pair samples of his recent curriculum, called “Vietnam in Verse,” which examined the era through poetry and songs like “The Ballad of the Green Berets” and “Eve of Destruction.” They were sold.

“For me, this just all seemed to fit,” said Bailey, who sketched the outline of what became the Hamilton curriculum on a flight to Milwaukee.

The goal was to immerse students in primary sources from the period, relying on Gilder Lehrman’s vast trove of more than 60,000 documents. These include a rare printed first draft of the Constitution and numerous letters from Washington, Jefferson, and more obscure Revolutionary-era figures such as Hercules Mulligan, the tailor who spied on British troops for the Continental army. Prior to performing, Bailey wanted students to mirror Miranda’s own writing process, including analysis of complex texts and creation of cogent arguments based on them.

Many of Miranda’s songs borrow liberally from these period documents. For example, the lyrics for “One Last Time,” which depicts George Washington’s decision to forgo re-election as president, introducing the country to the notion of a peaceful transition of power, are based on the first president’s farewell address. Chernow’s biography details how Washington relied on Hamilton to write the speech, and in the musical, the duet embodies their close partnership, with Washington’s commanding, gospel-infused croon rising above Hamilton’s spoken words — both characters hewing closely to the actual text of the address:

I anticipate with pleasing expectation that retreat in which I

Promise myself to realize the sweet enjoyment of partaking

In the midst of my fellow citizens, the benign influence of good laws

Under a free government, the ever-favorite object of my heart, and the

Happy reward, as I trust,

Of our mutual cares, labors, and dangers.

The curriculum also asks students to examine the tension between accuracy and historical integrity through close readings of two documents: Free Thoughts on the Proceedings of the Continental Congress, by the loyalist Rev. Samuel Seabury, and Hamilton’s response, A Full Vindication of the Measures of the Congress. The musical envisions a meeting between the two men on the road, and an overlapping battle of wits, in the song “Farmer Refuted.” Bailey’s 24-page study guide invites students to pinpoint where Miranda derived each of the song’s lines from and to determine what liberties he took.

In addition to the guide, students have access to a web portal where they can view excerpts from five songs and see actors reading and responding to source documents used in the show, from Hamilton’s love letters to the war correspondence of the Marquis de Lafayette.

One of the first signs Bailey had of the program’s impact was when he watched an EduHam promo video, in which four high school students are seen arguing over the effects of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense on Colonial opinion.

“Seriously? When does that happen?” Bailey remarked. “When do you catch high school kids between classes arguing about Thomas Paine? That’s just not reality. And yet it is.”

‘Street cred in the hood’

In the years since the first EduHam in New York, officials have accrued a short list of favorite student performances: the young black girl from Chicago who took on the persona of George Washington and sang the blues about his grueling winter in Valley Forge; in separate performances in Los Angeles, two Hispanic girls who offered takes on Abigail Adams’s famous letter to her husband imploring him to “remember the ladies”; and in New York, one student who imagined the life, mostly lost to history, of Maria Reynolds after her scandalous affair with Hamilton went public.

In Washington this fall, Duke Ellington alone had 141 EduHam projects, according to instructional coach Lisa Jones. They spanned six periods of American history and occupied a large chunk of each student’s afternoon “arts block.”

She estimates that 30 to 40 percent of the student body come from struggling families. Most teachers, let alone students, could not afford the show’s lofty ticket price, with some of the seats the students occupied normally going for upwards of $800. The play’s principals agreed to sell tickets to student matinees at break-even prices, with all but $10 paid for by national and local donors, including The Rockefeller Foundation.

Even if they normally wouldn’t find themselves in the show’s audience, students have no trouble seeing themselves in the story, Jones said.

“Alexander Hamilton knew how to craft an argument,” she said. “He was a real bad boy. Quite honestly, in some of the conversations the kids had, they were like, ‘Whoa, he had a lot of street cred in the hood with this argument.’”

“They discover that Hamilton had a little side action going on, that Hamilton was George Washington’s boy, that he came from the Caribbean and he wasn’t rich and was kind of the odd man out,” she added. “Going in, some of them didn’t know who Alexander Hamilton was. Now they will know. And they will see themselves in our nation’s history and understand also how they can affect it.”

As befits an arts school, Duke Ellington had plenty of top-flight entries to choose from, including several rap battles, a ballet, and even a full violin score. They chose the piece the students performed at the Kennedy Center after an internal competition.

The performances from other local public and charter schools included a narrative of the Boston Tea Party, a rap battle among the representatives of the original 13 colonies, and a hip-hop summary of the Bill of Rights.

Admittedly shy, Janelle Lott of Ballou STAY, an alternative high school, took to the Kennedy Center stage and recited a poem in the persona of Madison Hemings. Through strong DNA and circumstantial evidence, Hemings is believed to be the son of Jefferson and his slave Sally Hemings.

Identifying Madison as “one of his six mulatto children fallen in the cracks of history,” she concluded her piece by addressing Jefferson directly: “Father. Former president. Former vice president. Writer of the Declaration of Independence —” and then the rhetorical mic drop — “Hypocrite.” The audience roared.

Afterward, Lott said she was pleasantly surprised by the reaction. She said she relates to Hemings as a child who isn’t claimed by her father. “This isn’t something we talk about in my community. This isn’t something they’ll tell you in school. That’s something you have to dig for and figure it out all by yourself.”

When the lights went down on the big show at the Kennedy Center Opera House, the audience was silent but engaged. There were scattered titters as characters kissed, cheers at some of the Revolutionary-era trash talk (as when Jefferson dismisses Hamilton’s deference to Washington with “Daddy’s calling!”) and audible gasps at the dueling deaths of Hamilton’s son and, later, Hamilton himself, as if students were collectively trying to will a different outcome. Then, after the final act, a rousing standing ovation.

“We wanted to give these students an experience they’d never forget,” said Bailey of Gilder Lehrman. “The chance to hook students on the importance of what it means to be an American and to understand who we are as a country and their role in this nation and what it can be — you can’t put a price on that.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)