Highly Watched Pennsylvania School Funding Case Heads to Trial, Years After Low-Income Districts Sued to Overturn a ‘System of Haves and Have Nots’

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

A trial that’s been years in the making could spur drastic changes to Pennsylvania’s school funding scheme, long considered among the nation’s most inequitable and one that plaintiff districts accuse of creating a “system of haves and have nots” between low-income communities and their better-off neighbors.

Beginning Friday and available via livestream, the trial centers on a state funding system that relies heavily on local property taxes that plaintiffs allege provides inequitable state money to districts in areas with low property values and less personal wealth in violation of the Pennsylvania Constitution’s equal-protection provision. The current system fails to meet the commonwealth’s obligation to provide students with a “thorough and efficient system of education,” their attorneys argue.

The six districts who are suing will ask the Commonwealth Court in Harrisburg to declare Pennsylvania’s school funding system unconstitutional and order lawmakers to create a new one that directs more money to low-wealth districts. The non-jury trial of William Penn School District, et al. v. Pennsylvania Department of Education, et al., will include as many as 50 witnesses, who will present a dizzying array of statistics on school finance and its effects on student outcomes that could extend into January.

“This trial is really important for children throughout the commonwealth who are going to finally get the opportunity to tell the story of how they have been deprived of the opportunity for an effective education that so many students in well-funded districts in the state have the opportunity for,” Michael Churchill, an attorney with the nonprofit Public Interest Law Center, explained during a press conference Wednesday.

In addition to the six school districts, the lawsuit filed in 2014 is being brought by four parents, the Pennsylvania Association of Rural and Small Schools and the NAACP – Pennsylvania State Conference. Plaintiffs are represented by the Public Interest Law Center, the Education Law Center-PA and the law firm O’Melveny.

Defendants include the Pennsylvania Department of Education, the speaker of the House, the president pro tempore of the state Senate and Gov. Tom Wolf, a Democrat. The defense has argued that the legislature, not the courts, maintains authority over school funding.

“The question in this case is not whether Pennsylvania’s system of public education could be better,” Senate President Pro Tempore Jake Corman, a Republican, said in a statement, adding that lawmakers regularly pass bills to improve schools. “But imperfect is not unconstitutional.”

The case was previously dismissed by the Commonwealth Court, which agreed that school funding decisions are the responsibility of the legislature, not the judicial branch, but the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled the case must go to trial.

“It is a mistake to conflate legislative policymaking pursuant to a constitutional mandate with constitutional interpretation of that mandate and the minimum that it requires,” Justice David Wecht wrote in a 2017 opinion for the court majority.

In total, plaintiff districts allege the state’s schools are being shortchanged $4.6 billion a year, said Maura McInerney, the legal director at the Education Law Center-PA.

“Many of our witnesses will tell a common story about the impact of entrenched inequities in resources in low-wealth school districts,” she said. “That takes the form of overcrowded classrooms, antiquated science labs, nonexistent libraries and a lack of staffing in the school buildings as well as unsafe schools.”

The trial is one in a long history of similar school funding equity litigation that has found varying degrees of success. In neighboring New Jersey, in 1990 — nine years after the case was first heard in court — the Supreme Court found the state’s education funding formula unconstitutional and required lawmakers to direct more resources to low-income districts. The most recent high-profile example unfolded in Connecticut, where in 2016 lawmakers were ordered to completely reconfigure the state’s school funding system only for the Supreme Court to overturn the lower-court ruling two years later in a 4-3 split decision.

It is not the function of the courts “to create educational policy or to attempt by judicial fiat to eliminate all of the societal deficiencies that continue to frustrate the state’s educational efforts,” Connecticut’s then-Chief Justice Chase T. Rogers wrote in a 2018 opinion.

Even in some states where courts have found education funding schemes unconstitutional, the road to resource equity has been an uphill battle. In New York, lawmakers agreed in October to provide an additional $4 billion for schools to settle a legal battle that stretches back decades. In 2006, a state appeals court ruled the state owed schools more money to provide students a “sound basic education,” but the 2008 recession undercut state efforts to bolster funding, which is only just now being addressed.

Meanwhile in North Carolina, on Wednesday a Superior Court judge ordered the state to increase education funding by $1.7 billion. The issue stems from a 1994 funding equity lawsuit that alleged students in low-income communities weren’t offered the same educational opportunities as those in wealthier counties, claims the court agreed with three years later. More than two decades passed, however, before this week’s edict finally forced state lawmakers to come up with the money to fully satisfy the 1997 decision.

A growing body of research supports the notion that increased school spending leads to better educational outcomes for students.

In the Pennsylvania case, plaintiffs include the Johnstown School District where the middle school’s library remains locked because it lacks a librarian. In the Panther Valley School District, attorneys have blamed high teacher turnover on low pay and difficult working conditions, leaving the teachers who stay to manage increasingly large class sizes. In the Shenandoah Valley School District, a school psychologist works as an assistant principal.

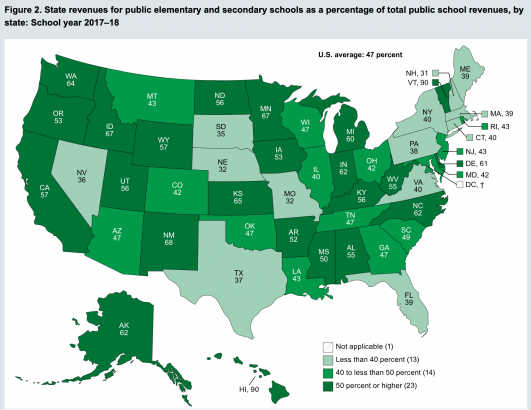

Overall, 38 percent of education funding in Pennsylvania is distributed at the state level, meaning districts have to rely on local property taxes for a larger share at 43 percent. That ratio ranks the commonwealth 45th nationally, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

On average, Pennsylvania’s wealthiest districts spend $4,800 more per student than its poorest districts, according to the Education Law Center, and that per pupil gap grew by more than $1,000 over the last decade after factoring for inflation.

While the state has increased education funding in recent years — and federal pandemic relief funding added an influx in new education money — the plaintiffs argue the disparities and funding levels remain unacceptable.

Critics have maintained, however, that Pennsylvania schools are adequately resourced and the “state share” is meaningless. Jennifer Stefano, the vice president and chief strategist at the Commonwealth Foundation, a conservative think tank, noted in a recent op-ed that Pennsylvania ranks within the top 10 nationally for overall education funding.

“Total spending per student is thousands of dollars above the national average, thanks to ample state funding and local funding that is far above what most local taxpayers in the rest of the country provide,” Stefano wrote. “It’s only because of this outsized local tax haul that an objectively high state funding level can be made to look small — basic fractions.”

But McInerney held that the state average funding is misleading. Pennsylvania is home to “many high-wealth communities and children are doing well in those communities,” she said. It’s the children in low-wealth areas, disproportionately youth of color, who are struggling. Half of the state’s Black students and 40 percent of its Hispanic students attend the 20 percent of school districts with the lowest wealth. Meanwhile, higher-income communities are able to raise more for schools through local taxes because they have a richer property tax base.

“Pennsylvania has some of the largest gaps between low-wealth and high-wealth districts of anywhere in the nation and they also have some of the greatest disparities in academic outcomes,” she said. “For example, 94 percent of students graduate in four years at our high-wealth districts whereas in poor districts, that percentage is 74 percent.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)