Here’s When the Supreme Court Says School Officials Can Block Critics Online

In an opinion that applies to district leaders, the court said the 'distinction between private conduct & state action turns on substance, not label.'

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

School board members can block constituents on social media only if they’re commenting on issues completely outside of their authority or sharing personal information, the U.S. Supreme Court said Friday, clarifying the First Amendment standard for governing on the internet.

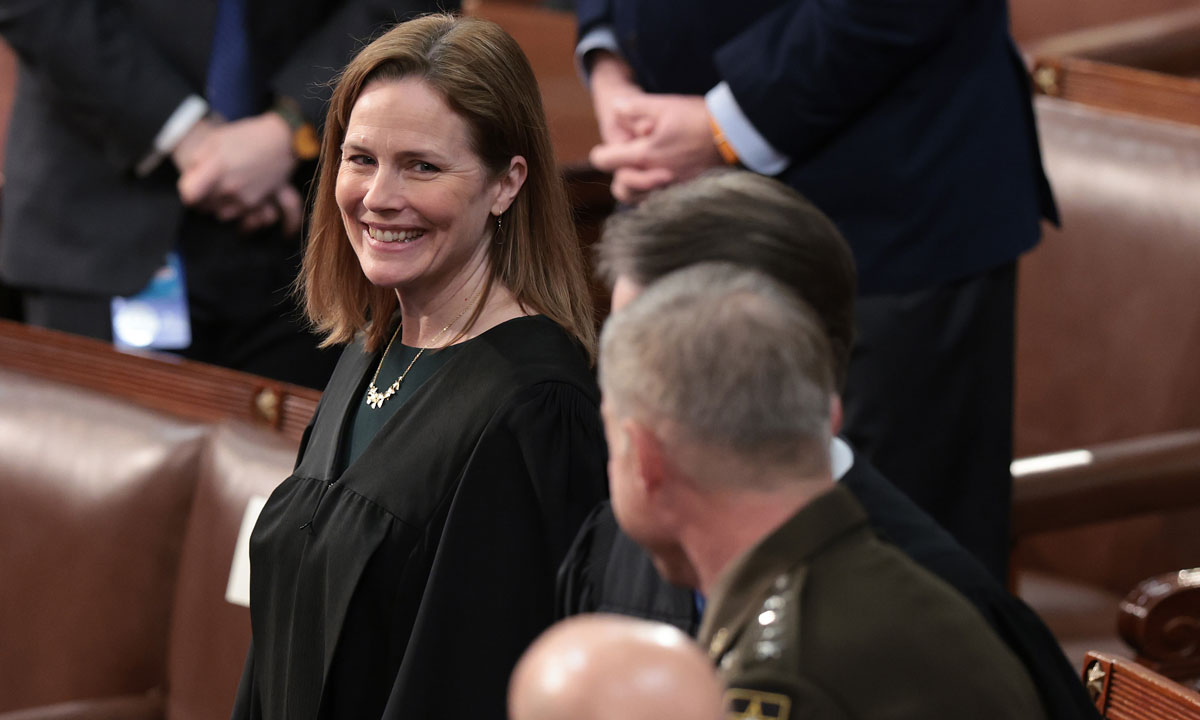

“The distinction between private conduct and state action turns on substance, not labels,” Justice Amy Coney Barrett wrote in a unanimous opinion in a case that involved a Michigan city manager but that “applies to all government officials.”

“For social-media activity to constitute state action, an official must not only have state authority, he must also purport to use it,” the court said. “If the official does not speak in furtherance of his official responsibilities, he speaks with his own voice.”

Now a federal appeals court must apply that standard to a California dispute in which two members of the San Diego-area Poway school board blocked parents who trolled the officials with lengthy and critical comments on Facebook and X.

Cory Briggs, who represents parents Christopher and Kimberly Garnier, said he thinks the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit will rule in his clients’ favor. He said Michelle O’Connor-Ratcliff, a current board member, and T.J. Zane, who served from 2014 to 2022, “possessed actual authority to speak as [district] trustees and in fact exercised that authority when they used the social media accounts at issue here to engage with their constituents.”

The case is one of four before the court involving social media this term. In Friday’s opinion, the justices sought to resolve a conflict among the appellate courts. The Sixth Circuit found that the Port Huron city manager did not act “under the color of law,” when he blocked a resident who complained about local efforts to prevent COVID. But the Ninth Circuit agreed with the Garniers, a couple who complained about how the board members handled both racial and financial matters. They argued that the board members used their accounts as extensions of their elected positions.

The opinion didn’t satisfy a leading First Amendment advocate who sued former President Donald Trump in 2017 over the same issue. Katie Fallow, senior counsel of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, said she was pleased the court said officials still have to uphold constituents’ rights to petition the government. But she said she was disappointed it didn’t go further, posting on X that the standard could be difficult to apply in many real-life situations.

“The Court did not adopt the more practical test used by the majority of the courts of appeals, which appropriately balanced the free speech interests of public officials with those of the people who want to speak to them on their social media accounts,” she said in a statement. “We hope that in implementing the new test crafted by the Supreme Court today, the courts will be mindful of the importance of protecting speech and dissent in these digital public forums.”

In her opinion on the Sixth Circuit case, Lindke v. Freed, Barrett offered an example of when an official might not be infringing on a citizen’s rights.

“Imagine that Freed posted a list of local restaurants with health-code violations and deleted snarky comments made by other users,” she wrote. “If public health is not within the portfolio of the city manager, then neither the post nor the deletions would be traceable to Freed’s state authority — because he had none.”

Even on social media, officials are allowed to have private lives, she said. But she also warned that if officials occasionally use personal accounts to address official business, completely blocking members of the public might prevent those citizens from commenting on those issues.

“A public official who fails to keep personal posts in a clearly designated personal account, therefore, exposes himself to greater potential liability,” she wrote.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)