Tweeting or Governing? Supreme Court Tries to Draw Lines in School Board Case

In separating public from private posts, Justice Elena Kagan said, 'there are First Amendment interests all over the place.'

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

In a case that considers the interplay of government and social media, the Supreme Court suggested Tuesday that public officials, like school board members, who carry out government business on Facebook and X don’t have a right to block their critics.

But some justices said the public deserves to know when the official is using their account as a private citizen.

“What makes these cases hard is that there are First Amendment interests all over the place,” said Justice Elena Kagan.

In the lawsuit, O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier, a California couple, said two Poway Unified School District board members violated their free speech rights when they blocked them on Facebook and Twitter, now X. Even if the accounts were personal, the parents argued, the members used them to discuss official school business.

“What you have is both of the petitioners using ‘we’ and ‘our’ when they talk about what the [school] board is doing,” said Pamela Karlan, who represents Christopher and Kimberly Garnier, parents of three children in the San Diego-area district. “Anybody who looks at that is going to think this is an official website. It looks like an official website. It performs all the functions of an official website.”

The board members insist that as private citizens, they had a right to restrict content. They objected to the Garniers repeatedly posting the same comments,and argued that the couple’s lengthy responses alleging racial discrimination and financial management were distracting and made it difficult for others to engage online.

Their attorney compared the board members’ social media accounts to personal property.

“The state itself did not control or even facilitate their operation of the pages,” said Hashim Mooppan. He added that his clients, Michelle O’Connor-Ratcliff, a current board member, and T.J. Zane, who left the board last year, “wielded no greater rights or privileges than any other private citizen denying access to their own property.”

Despite concerned parents and community activists packing school board meetings in recent years, the majority of public comment on schools, and on government policy in general, takes place online. That’s why the court’s decision will have implications far beyond education. The court on Tuesday also heard a similar case from Michigan that essentially asks the same question: When does a public official’s social media activity amount to “state action?” The cases are among five the court will hear this term that center on the role free speech plays in the digital sphere.

“I don’t think it’s immediately apparent which way they’ll go,” said Kristin Lindgren, deputy general counsel for the California School Boards Association, which submitted a brief in support of the board members.

Lindgren, who listened to the three hours of oral arguments Tuesday, said the three liberal justices appeared more sympathetic to the public’s right to know if their representative is acting in an official capacity, while the conservative majority focused on the board members’ freedom to discuss district issues as private citizens. “I don’t think the court wants to remove a public official’s private First Amendment rights to speak off the cuff.”

Regardless of the court’s ultimate opinion, she said it’s clear that both board members and the public need guidance on the issue.

Appearance matters, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit said when it ruled in favor of the Garniers. The opinion said the board members, “clothed their pages in the authority of their offices,” and that First Amendment protections “apply no less” to the internet than they do “the bulletin boards or town halls of the corporeal world.”

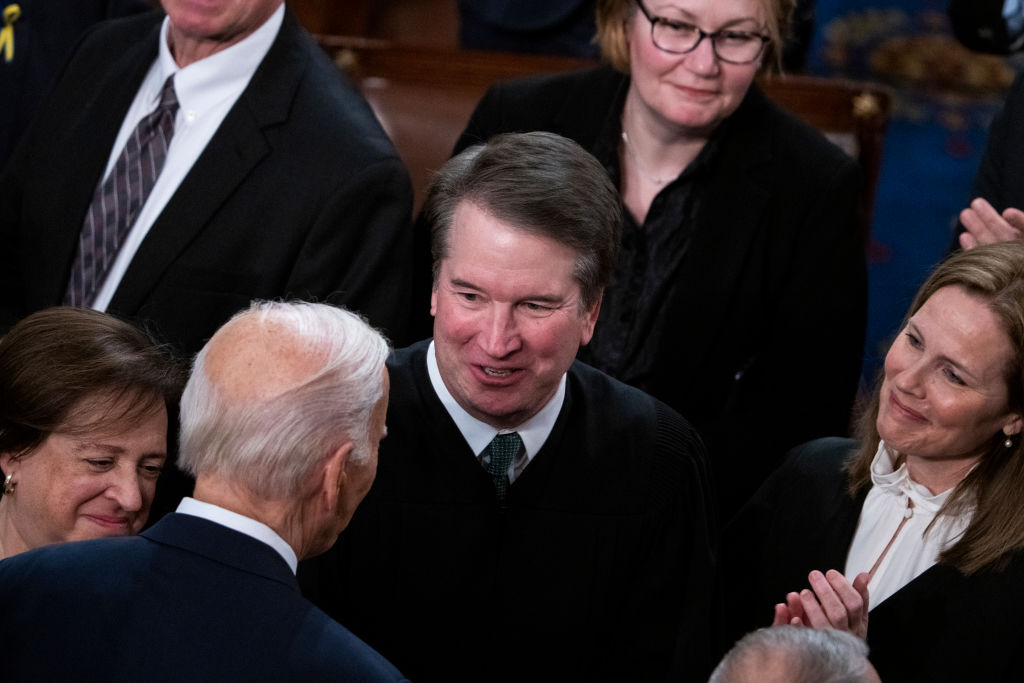

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, one of the court’s conservatives, said it may come down to whether constituents can get their information elsewhere.

“A lot of this will depend on whether it’s reposting or exclusive posting,” he said. “That’s the kind of practical information that people are going to need.”

The disclaimer issue

Justices devoted much of their time to the question of whether a public official must inform constituents when they’re speaking privately or in an official capacity.

“Government officials can operate in their personal capacity and in their official capacity,” Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson said, agreeing with Mooppan, the members’ attorney. But she added, “Why should they get to choose whether or not they’re doing one or the other without making a clear disclaimer? How do we know which you have chosen?”

Karlan noted that the Poway district even requires board members to “identify personal viewpoints as such and not as the viewpoint of the board.” But O’Connor-Ratcliff, she said, didn’t do that and predominantly used her Facebook page to communicate about school activities such as visiting classrooms during instructional time. “The only reason she has the power to do that is because of her official capacity.”

Mooppan countered that requiring officials to post such disclaimers is too heavy a burden and would have a chilling effect.

“Some of those people aren’t going to do it, and they’re gonna lose their First Amendment rights,” he said. “That’s the exact opposite of how the First Amendment normally works.”

The court’s opinion is likely to hinge on the extent of a public official’s authority, said Katie Fallow, senior counsel at the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University. For example, individual school board members don’t speak for the entire board.

But the second case, Lindke v. Freed, focuses on a city manager, who has more power to act individually. In that case, the Sixth Circuit ruled that the public official was acting completely on his own.

Fallow predicted the Supreme Court is unlikely to adopt the Sixth Circuit’s “very narrow” view.

“The court seemed to be indicating that it would use a test that considered whether a public official was using a private social media account to carry out the duties or exercise the authority of government,” she said. “The question is how broad and flexible that test will be.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)