For Students With Disabilities, Suspension Not Just a Matter of Race and Gender — But Geography

Exclusive analysis by The 74 of 2022-23 IDEA data reveals stark disparities among students already subject to disproportionate punishment in school.

By Amanda Geduld | June 24, 2025This story was published in partnership with The Post and Courier.

Carter was in first grade when the suspensions began. His mom describes it as the year “all hell broke loose.”

As he made his way through the public school system in York County, South Carolina, the now-15-year-old, who has multiple disabilities, continued to struggle.

The situation reached a crescendo in 6th grade, when Carter was suspended out of school for 7.5 days and in school about a dozen times, according to school district records and his mother’s estimates. This was in addition to numerous lunch suspensions — during which he was forced to sit at a table alone in the cafeteria — and bus suspensions, which meant Carter couldn’t ride school-provided transportation. His offenses, Kimberly Tissot, his mom, said, ranged from minor ones, like “incessant talking” and “cussing,” to the more extreme, including breaking one classmate’s glasses and threatening another.

While Tissot understands why these behaviors needed to result in clear consequences, she argued that every one of them was a manifestation of her son’s disabilities, which include ADHD, fetal alcohol syndrome, a disability involving written expression and a mild intellectual disability. They could have been avoided, she said, if Carter’s school had followed his Individualized Education Program, which lays out the supports and services the school is legally mandated to provide Carter so he can progress and learn.

Ultimately, her son, who has difficulty connecting his actions to their ramifications, was left confused and convinced, “he’s in trouble because he’s bad,” said Tissot, who is also the president and CEO of Able South Carolina, an advocacy organization.

Carter is one of hundreds of thousands of students with disabilities across the country who are suspended from school each year. It’s long been documented that this population of kids is generally more likely to face exclusionary discipline than their peers, but because of where he happens to live, Carter is particularly susceptible: No state removes students with disabilities from school for 10 days or fewer at a higher rate than South Carolina.

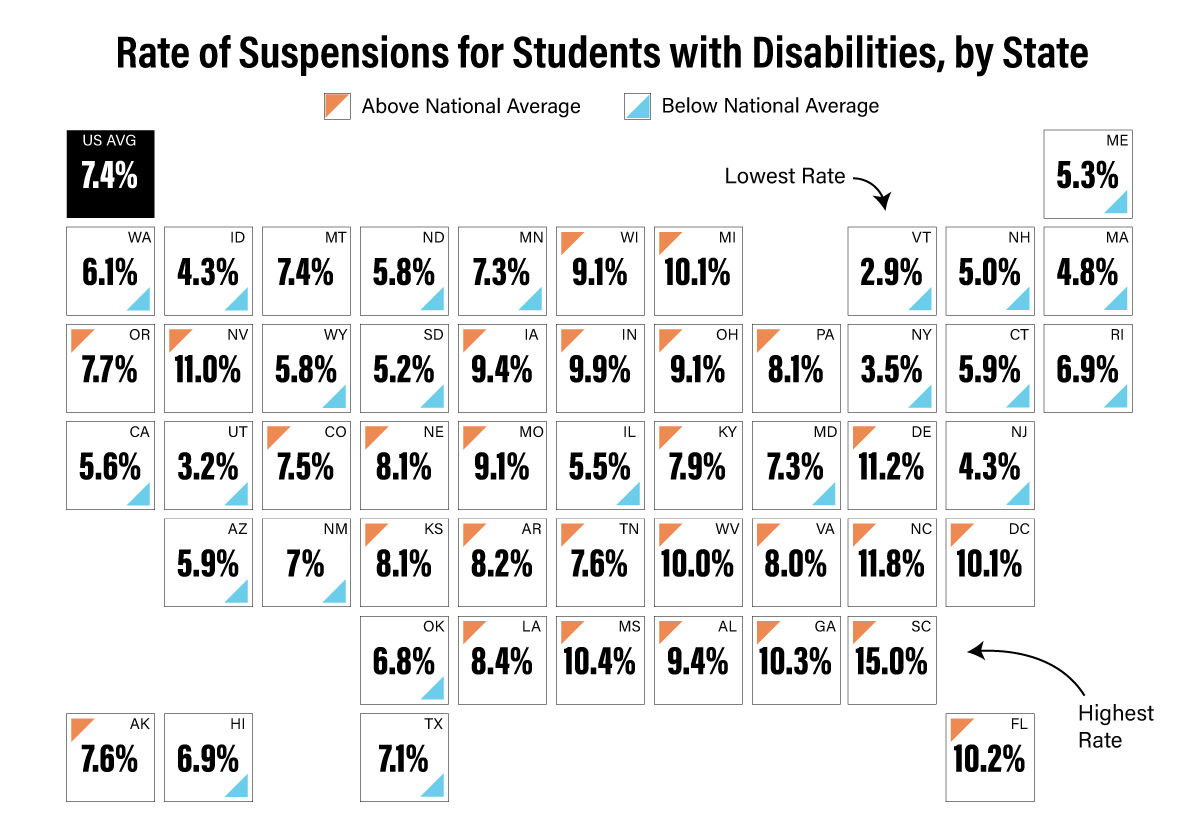

There, some 15% of special education students faced out-of-school suspensions for up to 10 days in the 2022-23 school year — nearly twice the national average, according to The 74’s analysis of the most recently available Individuals with Disabilities Education Act data.

These numbers may also be a substantial undercount, according to experts who told The 74 they’ve witnessed widespread “off-the-book” suspensions in South Carolina — in some cases to avoid the legal protections that kick in for students with disabilities once they’ve been kept out of the classroom for more than 10 cumulative days. Tissot said she was asked to pick Carter up from school without an official suspension on multiple occasions, a practice she knew to push back on only because of her advocacy work. And she said she only learned of some of Carter’s in-school suspensions, which weren’t all officially documented, from him.

Macaulay Morrison is assistant director of a health and legal advocacy clinic at the University of South Carolina Law School who represents special education families in their legal battles with schools.

“It’s just reflective of the state of public education of South Carolina as a whole,” Morrison said of the IDEA suspension data. “Sometimes it’s easier for schools to exclude these students than it is for them to figure out how to support them.”

In response to The 74’s findings, a South Carolina Department of Education official said they remain “committed to ensuring that all students, including those receiving special education services, are supported in safe and positive learning environments.”

The department has established a goal of working with districts to reduce suspension rates for students with disabilities to 9% or less — significantly lower than its current rate, but still higher than the national average — by working with advocacy and support groups, like the Behavior Alliance of South Carolina, to provide conferences, institutes and training opportunities.

And the department will continue to “closely monitor student discipline data to track progress toward this target … including assisting with district reviews of disciplinary referral data, revision of policies and procedures, and the development of targeted improvement plans at both the school and district levels.”

South Carolina was the only state whose numbers were not broken down by race after state officials notified the U.S. Department of Education of data quality concerns, according to federal Education Department staff. The South Carolina state education department official told The 74 that they provided corrected data once they were made aware of the issue, but that update was not reflected in the final federal dataset.

The federal Department of Education did not respond to repeated requests for comment from The 74.

The IDEA dataset is particularly significant because it’s the first to document disciplinary rates among students with disabilities at the national level post-pandemic, a time when schools were struggling to handle behavior problems among all students. The U.S. Department of Education’s more frequently scrutinized Civil Rights Data Collection has long shown disparities in discipline between students with disabilities and their general education peers but the most current available complete numbers are from the 2021-22 school year — when most kids were back to in-person learning but some districts were still offering a hybrid model and still others were allowing kids to learn virtually full time.

The 74’s analysis of the more recent IDEA data of some 7.5 million students with disabilities across three suspension categories reveals the differences experienced within this vulnerable student group. For example, in addition to South Carolina, special education students living in North Carolina, Delaware and Nevada are far more likely to be excluded from school than students with similar disabilities living in Vermont, Utah and New York.

The IDEA data, which is released annually, shows that race — also a well-established contributing factor to suspensions — plays a role among students who are already facing disproportionate discipline. While Black students made up 16% of all students with disabilities nationally, they accounted for nearly a third (31%) of all those students suspended out of school for 10 days or less.

In some cases, race and geography combined in striking ways in the IDEA data, such as in Nebraska, where almost 1-in-10 Black students with disabilities were removed from school for more than 10 days (a figure which includes in-school and out-of-school disciplinary removals) in 2022-23 — more than any other group in any other state.

Other key findings of the The 74’s analysis include:

- Nationally, boys are more likely than girls to be identified as having a disability, and — even when that’s considered — are disproportionately removed from classrooms: While about two-thirds of students with disabilities are male, they account for about 75% of special education students removed from school for any duration of time.

- On average nationally, just over 7% of all students with disabilities received at least one out-of-school suspension for 10 days or fewer.

- Black students with disabilities are disproportionately suspended out of school for 10 days or less in every state, to varying degrees. In Georgia, for example, they make up 39% of those with disabilities, but 59% of those who were suspended. In Delaware, Black students make up just over a third of those with disabilities, but over half of those suspended. In five states (Indiana, Nevada, Iowa, Nebraska and Wisconsin), at least 20% of Black students were suspended out of school for 10 days or fewer.

- In both West Virginia and Pennsylvania, almost 1-in-10 Hispanic children with disabilities were suspended for 10 days or less outside of school — more than any other state for this group, though closely followed by Nevada, Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin.

- In South Dakota, 17% of students with disabilities who identified as Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander were suspended for 10 days or less in school — a greater share than in any other state.

- California suspends students with disabilities for 10 days or fewer in school at the lowest rate (0.8%), and Vermont suspends them out of school at the lowest rate (3%).

- No state removes students for more than 10 days at a higher rate than Missouri (4%), 2.5 times the national average.

While supporters of stricter school discipline argue suspensions and expulsions are necessary to keep schools safe, research also shows that these measures are associated with a host of negative outcomes, including declines in academic performance, increases in absenteeism and depression, a lower likelihood of on-time graduation and greater involvement with the criminal justice system.

Longer and more severe exclusionary discipline, which children with disabilities are more frequently subjected to, does not seem to positively impact students’ future behavior and, for younger students, may even exacerbate it.

For students with disabilities, the loss of instruction time can be particularly devastating, said Amy Holbert, CEO of Family Connection of South Carolina, a training and information center for families whose children have disabilities. And especially when students receive out-of-school suspensions, it can put a strain on working families who suddenly have to scramble to find child care, she added.

These challenges have only worsened since the pandemic, according to Holbert, who said referrals to her organization for educational concerns have increased 128% since 2020.

The 74’s data analysis confirms “what advocates across the country have been saying over and over again about the students most likely to experience school pushout and get deprived of access to instructional time,” said Jennifer Coco, interim executive director of The Center for Learner Equity.

It holds up an “important mirror” she added, “on who is getting appropriate interventions and who are the students that we still collectively need to do better by.”

‘The Wild Wild West of civil rights enforcement’

Keisha Sims-Williams’ son, Savion, was just 2 years old when she began to suspect he might have a disability. He was hyperactive and impulsive. Sometimes she’d call his name and he wouldn’t respond. And he would often walk on the tips of his toes — a characteristic more common in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Some of these behaviors made starting school particularly challenging.

Sims-Williams said she told Savion’s Columbia, South Carolina, school as early as pre-K that he would need extra help. But instead of having him evaluated for an IEP they repeatedly removed him from school — both formally and informally — and ultimately relocated him to a transitional program, though not one for students with disabilities, she said.

“His pre-K year it got so bad, he was out of school more than he was in,” she said, estimating Savion was suspended for at least 30 days that year.

Ultimately, Savion was diagnosed with ADHD and autism by clinicians outside of school, but still he wasn’t evaluated for an IEP, which meant he went through his kindergarten year without the same protections around school removals as other students with disabilities.

As a kid with a suspected disability, though, he should have still had access to at least some of those guardrails, according to Morrison, the South Carolina attorney, who later filed a lawsuit on behalf of the Sims-Williams family.

And so, Savion had another year filled with so many removals his mom lost count.

“No child’s experiences in their education should have been as bad as my son’s. They ruined his good years of school.”

Keisha Sims-Williams

“At some point it was like they were on a mission to get rid of him,” she said.

In November of his kindergarten year, Sims-Williams filed a formal written request for an in-school evaluation, but his IEP wasn’t developed until May or implemented until the following August.

“It took two years of me fighting and pleading in order for him to finally get an IEP and be heard and seen as he should,” Sims-Williams said. She believes if that IEP had come along sooner, her son’s early years in school could have looked a lot different.

“No child’s experiences in their education should have been as bad as my son’s,” she added. “They ruined his good years of school. They ruined it.”

Much of this was confirmed by the state’s response to the family’s lawsuit. The South Carolina Department of Education found that the district had violated a number of Savion’s rights as a student with a suspected disability — including by not evaluating him for an IEP in a timely manner and not officially recording removals or creating a behavior plan once he hit 10 days of removals. These failures ultimately led to even more suspensions, according to court records shared with The 74.

Since extra supports were implemented, school has been significantly better for Savion. He’s been on honor roll, won awards and no longer cries when she drops him off each morning.

Still, “he’s had some bumps here and there,” she said, noting the now-7-year-old was suspended out of school for about eight days throughout first grade, but “compared to 20 or 30, that’s progress to me.”

“I’m hoping next year we’re down to five. Or none.”

Savion’s race, gender and disability status all make him particularly likely to be suspended, as does the fact that his family also lives in South Carolina. The Palmetto State leads the nation in preschool suspensions, as well.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act provides protections to students who have been removed from school for more than 10 days, but much of the enforcement is left up to schools, districts and states, leading to a patchwork landscape, according to interviews with over two dozen advocates, experts, parents and attorneys.

“Schools don’t seem to have any incentive to improve their processes and procedures because there isn’t anybody holding them to task,” said Mike Mathison, a juvenile justice resource attorney at the Children’s Law Center at the University of South Carolina Law School.

And in certain cases — like Savion’s — even if a student has a documented disability, it can be challenging to get schools to provide an IEP in a timely manner, leaving vulnerable kids unprotected.

The disproportionate removal of students with disabilities — especially for boys and those who are Black — experts told The 74 is the result of a confluence of systemic issues including discrimination, teacher and school counselor shortages and a dearth of training in positive behavior management techniques, like establishing strong relationships with students and clear routines. Added to that are administrators not understanding or enforcing students’ IEPs or the law, parents not knowing their kids’ rights, a return to top-down “zero tolerance” disciplinary policies and a lack of federal accountability.

This trend of disproportionality is well established: In the 2017-18 school year, 9% of students with disabilities were suspended, compared to 4% of their general education peers, according to a 2022 report from the Learning Policy Institute — largely based on analyses of four years of Civil Rights Data Collection. For Black students with disabilities, that figure was even higher: 20% were suspended.

Students with disabilities are also more likely than their peers to be punished for “broad and subjective categories” of behavior like defiance, according to a 2024 investigation by The Hechinger Report.

“There’s disadvantages of being Black when it comes to disciplinary outcomes, and there’s a disadvantage of being a student with a disability as well,” said Richard Welsh, associate professor of education and public policy at Vanderbilt University and author of Suspended Futures: Transforming Racial Inequities in School Discipline. “You can times that together … and that’s the definition of intersectionality.”

While disparities are cause for closer inspection — and can be evidence of discrimination — they alone are not proof of bias, cautioned Paul Morgan, director of the Institute for Social and Health Equity at the University of Albany. That being said, he added, even when controlling for differences in behaviors, Black students appear to be more frequently suspended than their peers. And a recent GAO report determined that Black girls are more likely to be removed from class than their white female peers for similar behaviors in the same schools.

Regardless of whether or not active discrimination is at play, the disparities are at least “a sign of weak systemic practices” and “a call to action,” said Coco, from The Center for Learner Equity.

Despite this, in April, President Donald Trump released an executive order saying he intended to roll back Biden administration discipline guidance, which encouraged school districts to collect, analyze and adjust their policies in light of disproportionate racial outcomes. Trump argued that approach actually weaponized federal civil rights laws in ways that discriminated against white students.

Critics have argued the executive order, titled Reinstating Common Sense School Discipline, will only further widen disparities for students of color and students with disabilities, especially as more than half a dozen states consider a return to stricter student discipline policies, including four that have already done so.

“Common sense is students in school every day learning, and students can’t learn if they’re not in school,” Coco said. “I recognize we need to keep schools safe, so to me a common sense investment is saying, ‘How do we ensure that schools are a place where students are getting access to what they need to thrive and be successful, both in terms of education and wraparound supports?’”

Trump has also been systematically working to dismantle the Education Department, which could mean even less federal accountability and data collection moving forward, said Dan Losen, senior director of education at the National Center for Youth Law.

“We’re in the Wild Wild West of civil rights enforcement,” he said.

A ‘huge oversight’ in IDEA enforcement

The federal law defining the rights of students with disabilities was first passed in 1975 and then updated and renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act in 1990. IDEA mandates a “free appropriate public school education” for eligible students ages 3-21. In the 2022-23 school year that included 7.5 million kids, or 15% of all those attending public schools — a two percentage-point increase from the 6.4 million students covered under IDEA a decade ago. The federal guidelines provide baseline regulations that states must follow, but some — like New Jersey — have implemented stronger protections as well.

Under IDEA, states must submit annual data about students who receive special education and related services to the Education Department, including the data analyzed by The 74.

And the law provides certain protections around disciplinary removals: If a student with a disability is removed from their classroom for more than 10 days, IDEA mandates a process called a Manifestation Determination Review, a hearing during which a group — including the parents and the student’s IEP team — meets to determine if the child’s behaviors were either related to their disability or the result of a failure to implement their IEP.

If the answer to either of these questions is “yes,” the school can’t move forward with the removal and has to instead make a plan to provide updated support.

Experts and parents told The 74 that once a student is diagnosed with a disability, schools tend to become particularly cautious about hitting that 10-day mark and triggering the legal review process. In some cases, that means educators pay closer attention to implementing a student’s IEP. But, in others, schools attempt to skirt the system by suspending students “off-the-books.”

And when schools do implement the hearing process, they don’t always do so thoroughly or with intention, sometimes just “doing [it] to check the box,” said Morrison, the South Carolina attorney.

A recent Chalkbeat investigation, for example, found that New York City’s public schools routinely flout these federal guidelines by not properly considering a student’s disability during hearings.

It can be challenging to hold schools and districts accountable for faithfully implementing these hearings, since the federal government isn’t collecting data around them, according to Losen, from the National Center for Youth Law.

“For monitoring the enforcement of these supposedly important protections, we don’t get to see any of that data,” he said. “Nothing. And I think that’s a huge oversight.”

Carter, the South Carolina student suspended multiple times throughout his school career, is now leading his own IEP meetings and learning to control his behaviors, his mother told The 74.

Tissot said he made it through the past school year without any suspensions — a first for him — and this fall he’ll start high school. His mom describes the teenager as a sweet, talkative kid who loves to try new foods — “He’s a little foodie!” — play video games and make people laugh.

While Tissot is proud of Carter’s progress, she also worries he’s still not where he needs to be academically, and his history of repeated suspensions has heightened his anxiety at school.

“He has told me that he tries so hard to control himself that he’s unable to concentrate,” she said.

And she worries for other students with disabilities who don’t have the same resources Carter has — like a mom who’s an advocate in the field — a fear that’s only intensified under the Trump administration.

“The future is not looking good for kids with disabilities who require IEPs,” she said. “It’s very scary because they’re taking away the federal oversight right now so really relying on parents to enforce it. And, I mean, that’s not going to work at all.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter