For Students to Succeed, Put High-Quality Curriculum in Teachers’ Hands

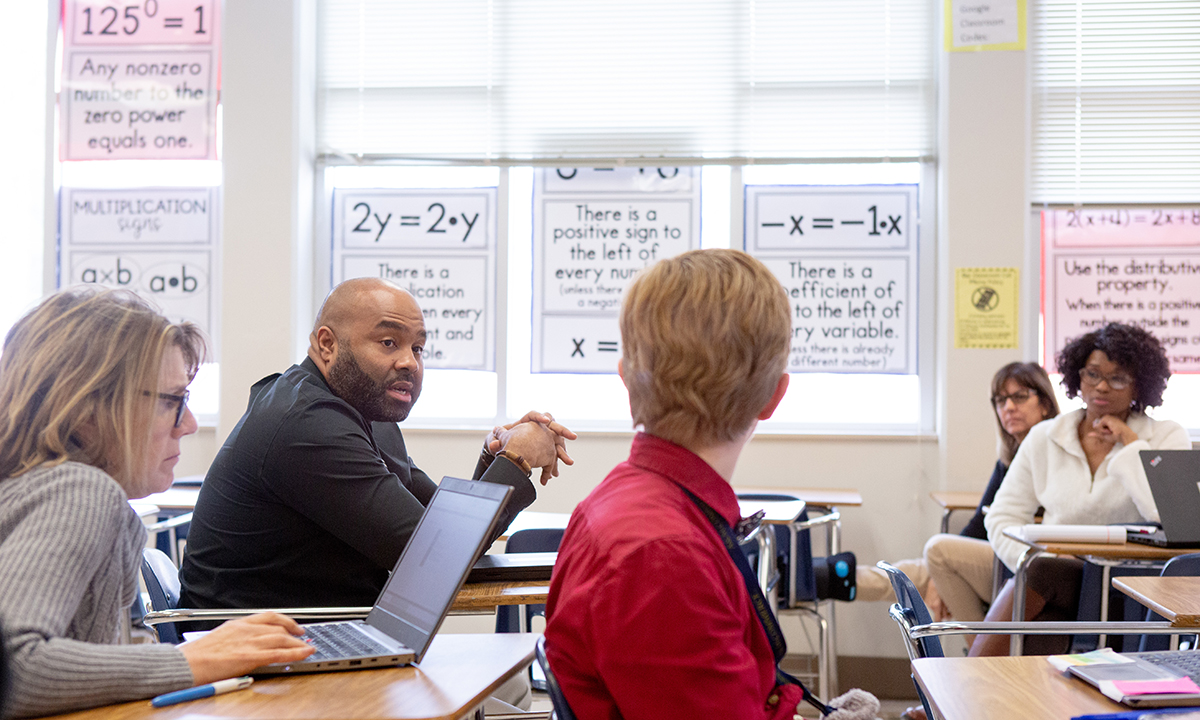

Without guidance on classroom materials or effective professional development, teachers may give students classwork not appropriate for their grade

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The recent National Assessment of Educational Progress results brought news that educators and families alike were dreading: Math and reading scores for 9-year-olds dropped to levels unseen for decades during the pandemic. Notably, average long-term math performance fell for the first time ever, and reading scores had the most significant drop in 30 years.

This may feel like cause for panic. But there’s one big reason for hope: Educators know more about improving teaching and learning than ever before. Rigorous research on emerging models of teacher development shows positive results for students hit hardest by COVID-19. And with billions of dollars in federal relief funding at their disposal, school system administrators and state leaders have the resources to take bold action.

Focusing on core instruction matters. School systems including the District of Columbia Public Schools and Chicago Public Schools made historic gains over the past decade because of innovative investments in instruction. But most districts have yet to take on similarly bold, structural efforts, retaining a status quo that works only for the few.

Here’s the challenge: Researchers assert that a high-quality curriculum can increase teaching quality, but less than half of educators report that their principal encourages them to use the recommended or required curriculum. Teachers also need ongoing professional development that helps them use quality materials. Only 1 in 3 teachers find their current options to be useful.

As a result, students spend the equivalent of six months per school year on assignments that are not appropriate for their grade. In 2018, TNTP found students in classrooms with mostly Black and Hispanic students were 3.6 times less likely to receive grade-appropriate lessons than those in classrooms with mostly white students. A majority of public school students now identify as children of color for the first time in U.S. history, meaning that most of these 9-year-olds will not be prepared for the world when they graduate in 2030 — unless their schools change course.

So what’s the solution? States and districts can take a few bold actions right now to turn research into practice. First, they can get better materials into the hands of educators. High-quality instructional materials have never been more available, affordable or adaptable. At least 13 states have created mandates, supports and strong incentives for districts to implement quality curricula. More should follow their lead.

While curricula have not historically reflected the experiences of students of color in meaningful ways, curriculum reviewers are meeting this challenge with tools for addressing diverse needs and incorporating students’ interests while designers catch up. Districts like Chicago Public Schools have even created their own standards-based materials to uniquely reflect their community.

Next, ensure that the support educators receive helps them excel at what and how they are teaching students. Recent research by the Rand Corp. in Chicago and Leading Educators in three cities shows that when teachers have frequent, well-structured time to work with colleagues on grade-appropriate instruction, their students make significantly bigger gains in test scores relative to those in other schools. Teachers who received this support in Chicago were able to significantly improve student achievement by more than the estimated learning loss from COVID. And students in D.C., Greater New Orleans and Greater Kansas City made an average 8.5 percentage point increase in math proficiency and a 5.3-point increase in English language arts proficiency. Over four years, these gains represent a 28% and 17% change, respectively.

Finally, gradually invest in the other conditions necessary for teachers to keep improving over time. These include a defined vision for excellent instruction, shared ownership for improvement across teams of teachers, curriculum and assessments that directly meet state expectations, and weekly collaboration time for teachers working in the same subject areas. Many schools add new initiatives and teaching methods for educators to incorporate in their classrooms, such as project-based learning and social and emotional support, without showing them how to combine these strategies into cohesive lessons. That can lead teachers to make false choices between goals like offering academic rigor and incorporating students’ interests rather than seeing those aims as reinforcing each other. Setting a shared, focused vision takes time, but it pays off.

Structural reform on the scale this moment demands is not easy. Even in places where there is strong will, union contracts, staffing shortages and state-level policy barriers limit how much change is possible. But schools must do right by the students and families who are counting on them. At this consequential time when there is little consensus on what schools should do next, education leaders must focus on how to prepare students for a changing world and help their teachers practice what they teach. Teachers make the future, but they cannot do it alone.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)