Five Months Ago, a Brooklyn Mom Filed a Due Process Complaint for Her Autistic Son. In the Midst of a School Closure and a Pandemic, Progress Is Finally Made

On April 13, Nicole Delpesche got the email she’d been desperate to receive: After five months in legal limbo, a hearing officer had finally been assigned to her case.

The single mom of a 6-year-old with severe autism, Delpesche had waited 157 days for movement on the due process complaint she filed with the New York City Department of Education early last November, asking that it pay for a private neuropsychological evaluation for her son, Caleb.

“I was relieved that at least something is happening,” said Delpesche, who has the right under federal law to file a complaint if she believes her child’s current school placement or services aren’t meeting his needs. “It’s been a long time that we’ve been waiting.”

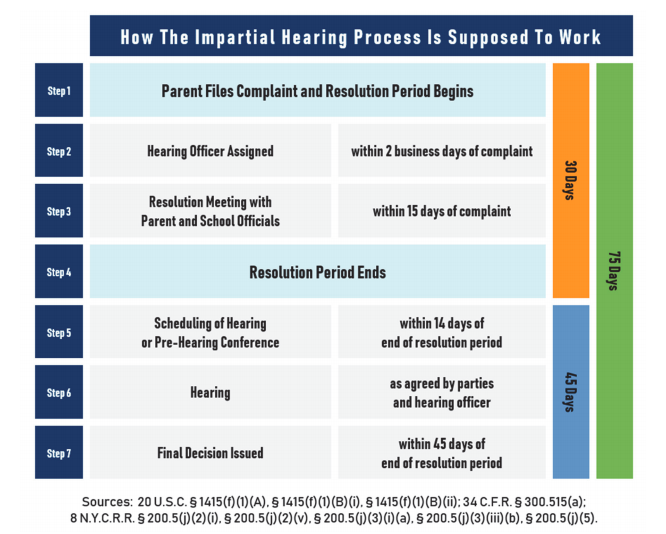

While the law also mandates that special education complaints be resolved within 75 calendar days, New York City misses that deadline nearly 70 percent of the time, with more than 10,000 cases clogging the system until recently.

The progress in Delpesche’s case coincides with the hearing office’s switch last month to telephonic hearings because of the coronavirus shutdown. That “has allowed us to increase our capacity to hold a greater number of hearings simultaneously than was previously possible,” a DOE spokeswoman wrote in an email.

That the welcome news would arrive during a pandemic that shuttered the public schools on March 16 and made Caleb’s learning situation even more precarious is a bit of an irony in what has been an increasingly arduous journey for him and his family. Caleb was diagnosed with autism at 18 months old, and his hyperactivity, restricted communication skills and anxiety in social settings has brought him to three different schools in two years. It’s also made the general education classroom that Delpesche had been holding out hope for impossible for her son.

The swift move to remote learning only compounded her fears of her first-grader falling through the cracks. A full-time student herself wrapping up five prerequisite courses for nursing school online, Delpesche, 40, has been continually torn between trying to guide Caleb through homework packets or letting him watch TV so she can finish her own assignments.

Schools in NYC are closed through the rest of the school year, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced earlier this month — leaving many parents of students with disabilities worried about the continuation of their children’s specialized services and the potential regression of academic and social skills.

“He’s so far behind,” Delpesche has said repeatedly since February, when The 74 first visited her and Caleb at their Brooklyn apartment. The evaluation, she hopes, would be able to pinpoint the source of Caleb’s difficulties beyond his general autism diagnosis and recommend more personalized interventions.

Delpesche’s complaint, filed under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, asks the DOE to cover the cost of evaluating Caleb, who’s on Medicaid. Delpesche says she can’t afford to pay the $6,000 up front to the provider she wants.

Low-income families, in particular, are “severely impacted” by complaint delays like those in New York City because they “have to wait for the hearing … in order to get the services” rather than paying out of pocket and requesting reimbursement, as more well-off families are able to do, Rebecca Shore, director of litigation for Advocates for Children of New York, told The 74.

Before April 13, there was near-radio silence on Delpesche’s complaint. She had entered a daunting logjam: The city’s special education system is massive and unwieldy — there are roughly 200,000 public school students with disabilities — and the hearing office in January had nearly 10,200 open complaints with only a handful of hearing officers taking on new cases. The average time to resolve a case this school year is 259 days, according to a January Board of Regents presentation.

The DOE, which was sued alongside the state education department in February by special education families and their advocates because of the delays, says it’s continuing to address the problem, citing the progress made during the school closure. From March 16 through March 27, for example, hearing officers accepted appointments for 196 cases — a 145 percent increase from the prior two-week period. The number of open cases had dipped to 9,444 as of April 17.

“The NYCDOE and hearing officers remain committed to providing due process and reducing the backlog of cases waiting for an impartial hearing,” the spokeswoman said. She noted that there were 66 hearing officers in rotation as of last week; how many are actively accepting new cases “changes daily based on the hearing officers’ declared availability and is not static.”

It’s unclear right now when Delpesche’s hearing will happen, though her lawyer said Monday she’s working to arrange a date in May. Emergency rules passed by the state Board of Regents earlier this month allow hearing officers to extend cases up to 60 days past the 75-day resolution deadline while schools are closed, rather than the existing 30 days. There’s also the question of how accessible a neuropsychological evaluation would be during the crisis.

But after a winter of waiting, Delpesche is clinging to this newfound hope.

“I’m very, very excited to see what’s going to happen now,” she said. “I’m truly hopeful that some[thing] will come out of it.”

As difficult and uncertain as the situation is now for her and the rest of the world with schools closed and the economy locked down, Caleb’s prospects look better in April than they did just a few months ago.

February

Sitting at the kitchen table in the family’s Crown Heights walk-up on a Thursday night in late February, Delpesche began recalling milestones in Caleb’s life and his struggles to learn.

As she spoke, Caleb hopped and darted around the living room on all fours — a pair of his 18-month-old sister’s pajamas either on his head or fastened around the back of his pants as a makeshift tail. Alphablocks, a TV show geared toward young readers, played in the background. He couldn’t seem to focus on it for more than a minute or so.

“Who’s at the door?” he asked repeatedly, sporadically curious about the stranger asking his mom questions.

The first sign that Caleb was on the autism spectrum, Delpesche said, was when he never crawled. He went straight from sitting upright to walking and, at 18 months, was only speaking one or two words. Around that time, he was formally diagnosed with autism. While he started receiving speech and occupational therapy at 2 years old, she said those early interventions were “inconsistent.”

Delpesche has moved Caleb to three schools in the past two years, including a District 75 school for kindergarten. While D75 schools are tailored to serve students with severe disabilities, Delpesche said the environment was “not appropriate” for Caleb because he mimics his peers’ behaviors. He’d have meltdowns during the day and come home banging his head against the walls.

Caleb has attended Excellence Boys Charter School Elementary Academy in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn since September, spending his days while school was still open with a designated teacher and paraprofessional, separated from his peers.

“The school was trying to merge him into the general population [for the first few days],” Delpesche said, “but he was constantly being overwhelmed.”

While the school “has informed me a lot more about autism,” Delpesche said, she doesn’t believe it’s fully equipped for someone with Caleb’s level of learning challenges. “They’re trying their best … but it’s not the environment for him,” she said.

Students with disabilities at Caleb’s school, part of the Uncommon Schools network, receive “a full spectrum of supports,” chief media officer Barbara Martinez wrote in an email statement — including individual counseling and instruction. She added, “We are committed to serving students with disabilities within our schools, and our interventions have led to enormous progress for our students with autism.” Uncommon Schools said it was unable to comment on Caleb’s situation specifically because of student privacy laws.

Charters are publicly funded schools that are independently run. While they have a responsibility to accommodate the Individualized Education Programs of students who enroll, the city’s DOE, per New York State law, is ultimately responsible for ensuring that students with disabilities in charter schools get appropriate supports and services.

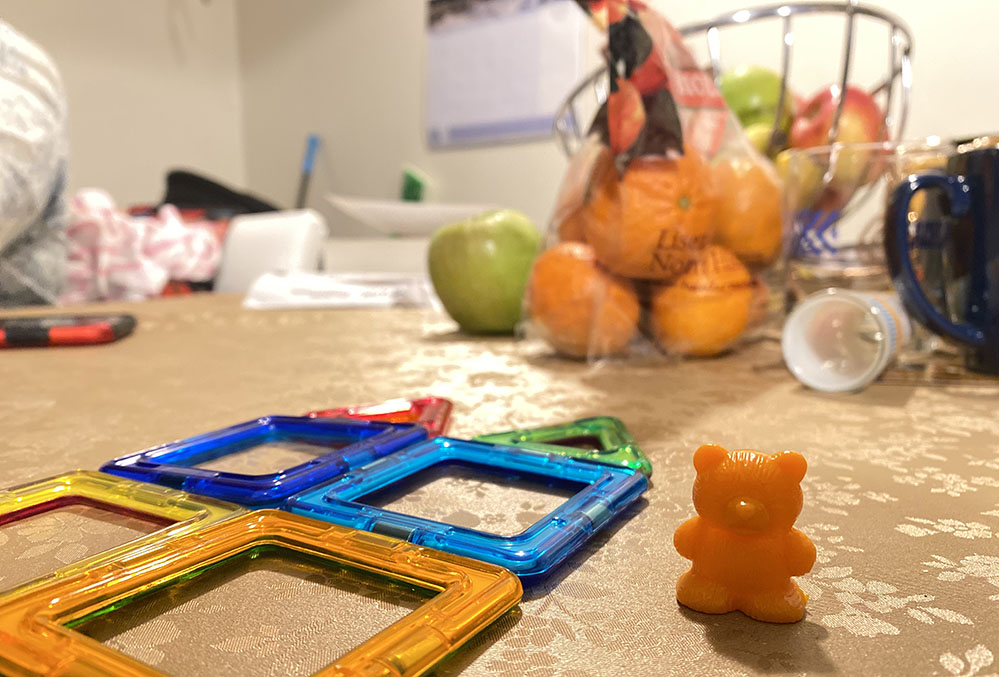

Sometimes, Delpesche attempts to teach Caleb herself. The two stop and try to spell out words on signs when they’re walking on the street. She bought a bunch of small, plastic orange bears to explain basic concepts of subtraction and addition.

He needs teaching that is more hands-on, not auditory, she’s learned. Sometimes it clicks. “He’s very smart in his own way,” she said.

Caleb, who’s turning 7 in June, still can’t read, Delpesche said — that eats at her the most. He wrestles with writing and tracing letters, too, and just learned how to say his full name.

“I’m scared,” she said. “He’s suffering, and in turn, I am suffering. My career is suffering. Financially, I’m suffering.” While Delpesche gets child support from Caleb’s father and occasional help from her 19-year-old daughter, she’s raising Caleb on her own. Before she started taking classes at Borough of Manhattan Community College, Delpesche worked as a patient care technician at Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center, drawing blood from patients and taking their vitals. She dreams of becoming a mother-baby nurse.

For Delpesche, the biggest barrier to Caleb’s success is not wholly understanding his learning needs and, therefore, not knowing the best personalized interventions and school placement for him. He’s had an IEP since he was 5 and receives speech and occupational therapies along with counseling. But until he’s more rigorously evaluated, she believes his current accommodations are not as responsive as they could be.

A neuropsychological evaluation, she’s certain, would provide clarity. The evaluation examines how the brain functions — measuring cognitive skills like attention span, memory and language — and how that functioning impacts behavior and learning. It’s typically broader in scope than the psychoeducational evaluations that the DOE offers in-house, yielding a larger set of data to identify why a child has certain difficulties, their learning strengths and weaknesses and the best services in and out of school.

“I believe that once he gets into an environment where he can be able to be trained, be taught and be coaxed — to have an opportunity to do better — he will succeed,” Delpesche said. In her own research, she’s eyed the hands-on Montessori schools and the private Gillen Brewer School on the Upper East Side. “But [the DOE] can’t place him in an environment if they don’t know who he is.”

It’s also strategic, she noted; getting the evaluation and more specific diagnoses can boost a lower-income family’s chance of qualifying for state agency assistance and receiving insurance coverage for services like Applied Behavior Analysis therapy, which focuses on improving behaviors such as social skills, communication and reading.

Although federal law requires schools to evaluate students at no cost to families, it doesn’t require the district to provide the best evaluation possible. But Delpesche’s lawyer, Bonnie Spiro Schinagle, said a student with severe autism like Caleb warrants a more comprehensive and robust examination than what the education department can offer.

“Some of the people we could go to [via the DOE] would be ‘good enough,’ they would get her information that she needs,” Schinagle said. “But this kid has never really been looked at. In my opinion, he requires a really sophisticated pair of eyes on this.”

She added that the $6,000 fee is “a going market rate.”

April

During a phone call in early April, Delpesche’s now 20-month-old daughter babbled in the background. Caleb wanted water. One of them tore up their mother’s homework. A subsequent call on a late April morning was cut short; Delpesche struggled to talk over her kids’ wailing.

It’s been “really tough” supporting Caleb’s learning and her own since schools closed in March, she said.

Delpesche says she hasn’t been able to step into the quasi-homeschooling role many parents have been forced to adopt in recent weeks because she’s drowning in her own schoolwork. Her five classes are now online, and Spanish assignments alone can take three hours a day, she said. And finals are just around the corner.

Caleb’s services have expanded in the month and a half since schools closed, filling up some time. He started remote learning with a two-week modified homework packet — with activities like tracing his name — and calls with a speech therapist who’s “really good” for a half hour, three times a week, Delpesche said. Now, he’s also connecting with a counselor once a week, and occupational therapy started last week too.

From what she’s observed, the specialists work with Caleb on skills like “teaching him full sentences and how to express certain types of emotions, and the representation of [those emotions] physically,” Delpesche said. She anticipates virtual instruction getting added to the mix as well after acquiring an iPad in the past week from the education department to get Caleb online.

When asked if she was happy overall with the current level of instruction, Delpesche seemed ambivalent. “It could have been better, but so far, I can only accept what I get now,“ she said.

City schools earlier this month had to submit remote learning plans detailing how accommodations would continue for students with disabilities, though they’ve been granted flexibility to reduce services in some cases. Charters did not have to fill out the same template as district schools but sent plans to their respective state charter authorizers.

In an email statement, Uncommon Schools’ chief media officer Martinez emphasized that the system has developed “a robust learning platform online” where “students with special needs get additional supports to stay on track.” She added that the staff’s “number one priority is the health and well being of all of our families during these difficult times. … We stay in constant contact with parents and guardians so that they are not only part of the planning for the child’s growth but that they are aware daily of the progress their child is making.”

It remains unclear when New York City schools will reopen. Mayor de Blasio earlier this month said the city is preparing to reopen the system in September. Under Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s current order, schools are closed through May 15, although the governor has begun to talk about reopening the state in phases and said he would make a decision regarding schools later this week.

Even through the unprecedented changes of the past few weeks, Delpesche’s intention for her son remains the same. And, perhaps remarkably given the chaos caused by COVID-19, one that seems more attainable now with a hearing officer finally assigned to her case.

“For him to be where he’s supposed to be,” she said. “That’s my goal.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)