First-Ever Study of Mexican-American School Desegregation Finds Marked Gains for Chicano Students

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The first major judiciary win for K-12 school integration in the U.S. did not come in 1954 as the common narrative goes, but in 1947. Nearly a decade before the landmark Brown v. Board case, a federal District Court judge in Orange County, California ruled in Mendez v. Westminster that it was illegal to separate Mexican and non-Hispanic white learners into segregated schools.

But until recently, it remained unclear what impact the decision had on California’s Chicano students.

This spring, in a working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, scholars Francisca Antman and Kalena Cortes filled the gap with the first-ever quantitative analysis of the case’s long-run impacts.

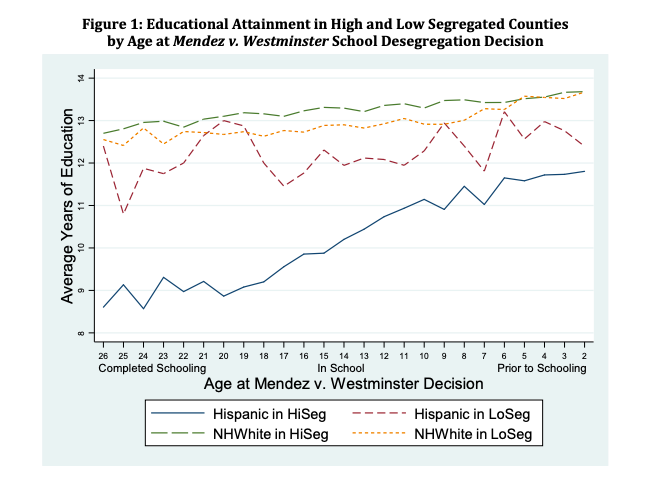

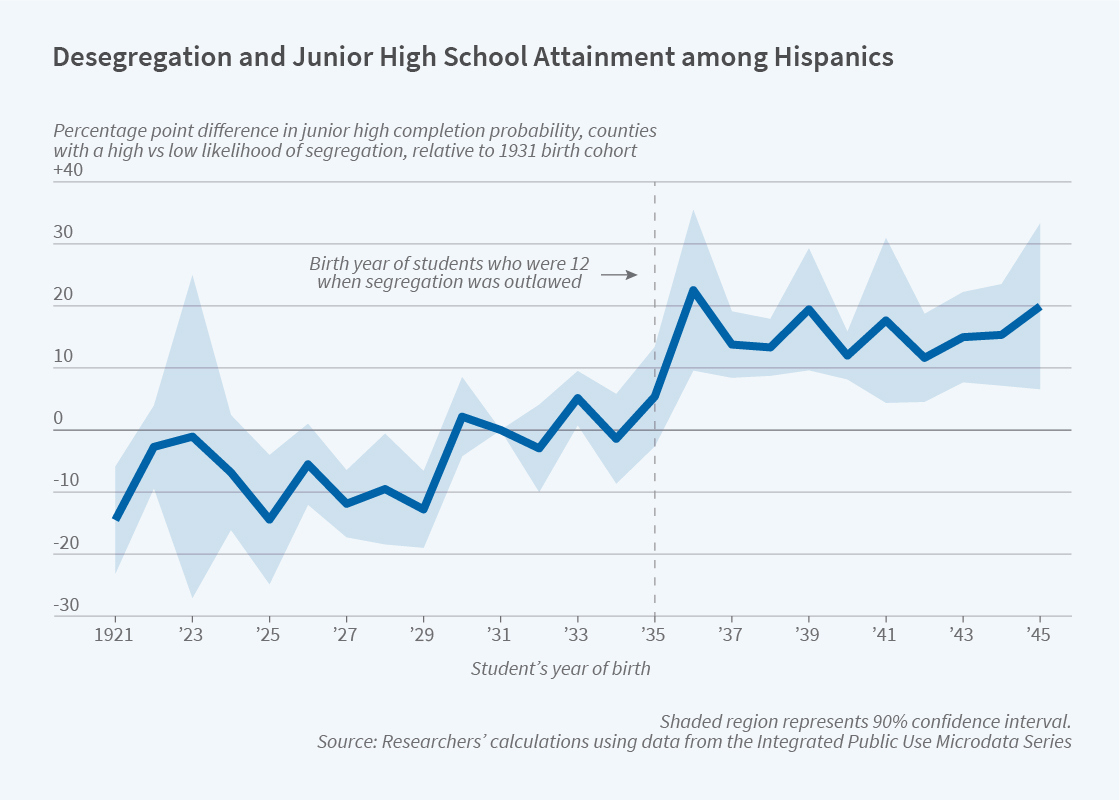

Participating in desegregation, they found, led to a significant increase in educational attainment for Mexican-American students. Those born after the ruling completed nearly a full year of schooling more than a comparison cohort born 10 years prior and were nearly 20% more likely to graduate from high school. In the decades following the case, Chicano students in highly segregated counties were able to cut by more than half the disparity in their schooling outcomes with those of Chicano students in minimally segregated counties.

“What we see is really a dramatic rise in educational attainment for Hispanics after the end of de jure segregation,” said Antman, an associate professor of economics at the University of Colorado Boulder. That finding, she noted, held true “particularly in those areas that we think were most likely to be segregated.”

In California before the Mendez decision, segregating Mexican-American students into separate schools was common practice, driven to a large extent by racial discrimination. Those who advocated for separate schools claimed Hispanic students were unclean, intellectually inferior and lacking English language skills — even though Mexican-American youth who did not speak Spanish were also segregated.

Today, Latino residents make up one-fifth of the U.S. population and an even larger share of the nation’s public school student body. Yet Latino youth continue to be among the most likely to attend segregated schools. Analyzing the Mendez decision is key to understanding the present circumstances for Latino students and families, the authors argue.

With desegregation, Antman explained, “Hispanic students [began to] have access to white classrooms or schools that they didn’t before” — meaning more resources and improved facilities. Though exact data on the flow of financial resources does not exist, she and her co-author hypothesize that such shifts may have triggered the outsized benefits for Chicano youth.

At the same time, education outcomes improved for all learners, Mexican-American and white students alike.

“Educational attainment is rising for all groups,” she said, adding that students nationwide tended to complete more schooling over the time period her study observed.

There is no official record of which areas separated Mexican-American students into separate schools as exists for school segregation in the American South — posing a major obstacle to research on the topic. That did not stop Antman and Cortes.

“A lot of times, researchers only pursue questions that they can answer [cleanly with existing data],” said the CU Boulder economist. But “sometimes the question is so important that you want to pursue it even if you can’t get the absolute best, clearest answer.”

She and her co-author got around the limitation by using 1940 census data to create a proxy measure for segregation levels. According to historical accounts, areas with the highest share of Hispanics in their population were the locales with the most rampant segregation. The researchers then identified the top quarter of California counties with the highest share of Hispanic residents and compared them to the bottom quarter with the least to represent high- and low-segregation counties.

In another key hurdle, records are also absent on how effectively each school district followed through on the desegregation effort. Implementation varied at the local level with some districts opening separate schools or maintaining segregation in certain grade levels while desegregating others. The authors account for the messy rollout using what’s called an “intent-to-treat” approach that includes all students in their analysis, regardless of their district’s follow through on desegregation. The method simply measures the effect of students’ exposure to the legal change. If anything, the approach would understate the impacts of integration, the authors explain, by grouping students who experienced desegregation together with those who remained separated.

As with the Brown case, impacts grew over time, Antman and Cortes found. Mexican-American students who were toddlers at the time of Mendez were likely to complete more total years of schooling than those who were in primary school (who in turn were more likely to see higher educational attainment than their older peers). Achievement gaps between Chicano and white students closed over time.

Compared to cohorts that began school before Mendez, those who matriculated after segregation was outlawed were 18.4% more likely to graduate from junior high school and 19.4% more likely to graduate from high school, the analysis revealed.

Fast forward to the current day, and school segregation levels nationwide have crept upward for decades — with a pronounced increase for Latino students, who continue to have higher dropout rates than any other racial or ethnic group in the U.S. and have been hit especially hard by the pandemic. With that backdrop, Antman said her results underscore the continued need for integration.

“Some might might say, ‘Well, would it really matter to desegregate [in the present day]?’” she said. “This certainly would suggest that it would matter very much.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)