Community Eligibility: The Key to Hunger-Free Students or Just a Band-Aid?

20.8% nationwide growth in CEP participation fuels conversations on the need for universal free school meals in public schools.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As a working mom and full-time college student, Javonna Brownlee understands the struggle of providing school meals for her three young children.

From balancing a packed schedule to not always having the means to buy groceries, Brownlee is grateful her Virginia school continued to provide free breakfast and lunch for all students despite the expiration of federally funded pandemic school meals at the start of the 2022-23 academic year.

“I don’t have one of those stay-at-home mom lives where I’m able to pack their lunch every day,” Brownlee told The 74. “So even if I know the food isn’t everything they might want, it’s at least something to get them through the day.”

Although Virginia has not passed free school meals legislation in the absence of the federal program, Virginia and many other states are now participating in the Community Eligibility Provision, or CEP — an Obama-era program that allows schools with high poverty rates to provide free breakfast and lunch to all students.

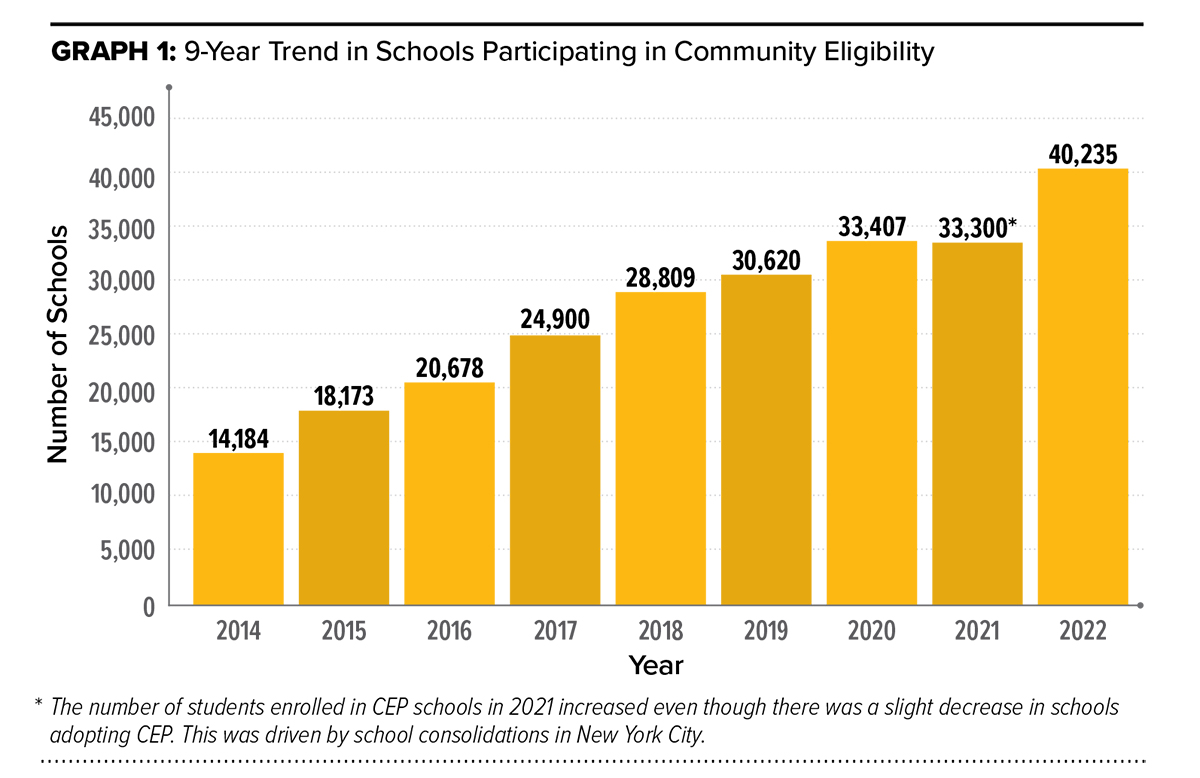

According to a report from the Food Research and Action Center, CEP participation soared in the 2022-23 academic year with 40,235 schools nationwide taking part — an increase of 6,935 schools, or 20.8 percent, compared to the previous year.

CEP began through the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 where any district, group of schools or individual school with 40 percent or more students eligible for free school meals can participate.

Today, 19.9 million children across the country attend a school that has CEP — an increase of nearly 3.7 million children, or 22.5 percent, compared to the previous year.

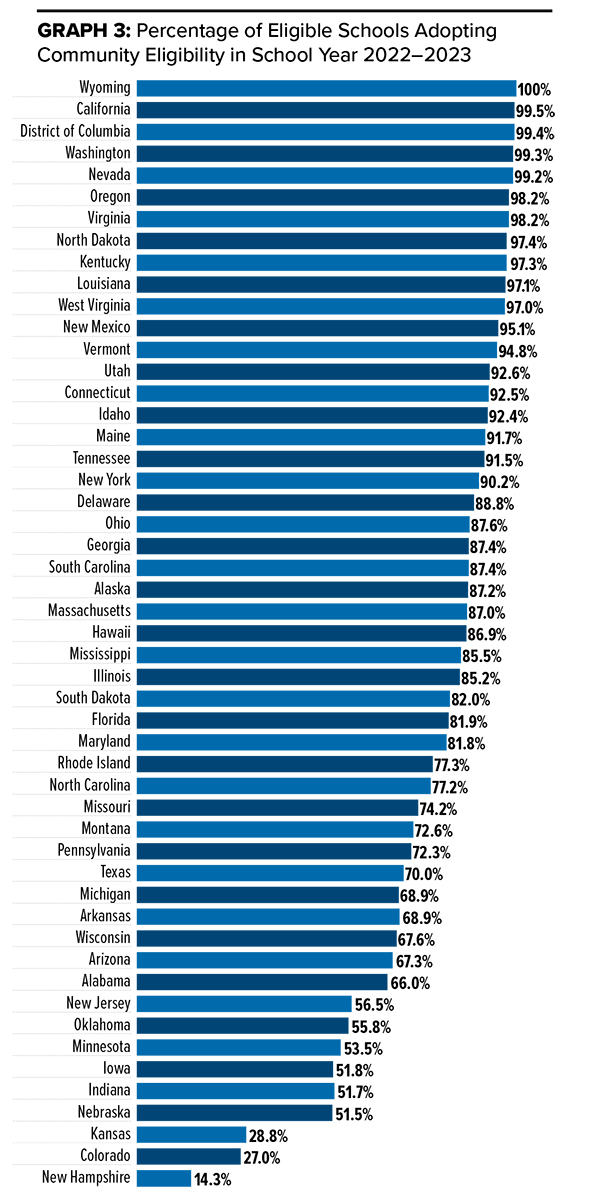

Participation rates vary significantly state-by-state, from nearly 100 percent of eligible schools in Wyoming, California and the District of Columbia to under 30 percent of eligible schools in New Hampshire, Colorado and Kansas.

Crystal FitzSimons, the director of school and out-of-school time programs at the Food Research and Action Center, said CEP participation has grown in almost every single state.

“Most schools did not want to go back to the way school nutrition programs operated prior to the pandemic so they really leaned into community eligibility,” FitzSimons told The 74.

Cheryl Johnson, the director of child nutrition and wellness at the Kansas Department of Education, said the state’s low 28.8% CEP participation stems from how it negatively affects schools’ finance formula.

“Many school districts are hesitant to move away from using meal applications because it can greatly impact their at-risk funding for students,” Johnson told The 74.

Johnson added how schools participating in CEP lose important student data from no longer having to fill out applications for those receiving free or reduced price meals — thus causing schools to potentially receive less funding from the state.

But FitzSimons said Johnson’s concerns are not the case.

“A lot of times school districts would distribute Title I funds using free and reduced price eligibility, but they don’t have to do it that way,” FitzSimons said. “When community eligibility passed, the U.S. Department of Education actually came out with guidance to help districts come up with ways to distribute these funds among their schools.”

A U.S. Department of Education spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

Allie Pearce, a K-12 analyst at the Center for American Progress, added how schools shouldn’t shy away from CEP because there is a need to change how schools structure their finance formulas.

“Free and reduced price eligibility is an imperfect measure of students’ socioeconomic status but it’s the predominant one that’s used,” Pearce told The 74. “We really need to move away from free and reduced price eligibility as this proxy measure and move towards other measures that are more representative of students and their families.”

Pearce recommends schools look at household income, students’ Medicaid participation and neighborhood poverty rates from the U.S. Census Bureau among other data points.

“There are a lot of things we can use, and it probably makes the most sense to use a mixed measure as much as possible since that will paint a clearer picture,” Pearce said.

Frank Edelblut, the New Hampshire Education Commissioner, noted how the state’s low 14.3% CEP participation comes from having few schools eligible.

“It’s just hard to get a whole broad swath of schools that are going to participate because they don’t qualify,” Edelblut told The 74.

To address this concern, the U.S. Department of Agriculture proposed a rule in March 2023 to lower the CEP eligibility threshold from 40 percent to 25 percent.

“This proposed rule will make CEP available for about 20,000 more schools,” a USDA spokesperson told The 74 in an emailed statement. “USDA estimates that about 2,000 schools with roughly 1 million children enrolled will opt into CEP because of this rule.”

But Pearce strongly believes “the logical and equitable next step is a universal system full stop.”

“Expanding community eligibility now is needlessly regressive when it comes to the pandemic era waivers we’ve already offered,” Pearce said. “It doesn’t address the ongoing meal debt burdens or some of the longstanding struggles associated with the meal application process in schools.”

Johnson agreed, adding that despite Kansas’ low CEP participation, free school meals for all students would be a “win-win” situation.

“It would reduce paperwork and reduce stigma dramatically within the state if universal free meals were ever considered by Congress,” Johnson said.

Kerri Link, the nutritions program supervisor at the Colorado Department of Education, said the state addressed the low 27% CEP participation by passing free school meal legislation starting in the upcoming 2023-24 academic year.

Colorado now joins California, Maine, Minnesota, New Mexico and Vermont that have acted to independently fund free school meals.

Until statewide measures transition to federal investment, Pearce said CEP participation still serves as an incremental step forward.

“It may not go far enough to meet the needs of schools across the country, but in general, it’s a great step towards free meal access for more students,” Pearce said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)