Federal Probes into Lack of School Services for Special Needs Students Reflect Nearly a Year of Parental Anguish, Advocates Say

Luis Martinez, an 11-year-old fifth grader with autism, rarely missed a day of school before the pandemic. Though non-verbal, he delighted in seeing his friends and teachers, and his mother, who quit her job five years ago to care for him, was thrilled for his small gains in communication.

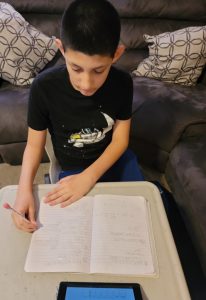

But that all changed during the shutdowns: Luis, a student in the Los Angeles Unified School District, has logged 14 absences since fall and no longer makes any attempt to interact with his peers online. After 10 months of remote education, he barely looks at his tablet during class and acts out nearly every day, scratching and biting himself and members of his family out of frustration.

“He almost never threw tantrums during in-person learning,” said his mother, Tania Rivera, speaking through a translator. “This has been a very difficult experience. He cries a lot. We both do.”

Rivera believes LAUSD should have done more for her son, and other parents within her district feel the same. Their complaints reached the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, which opened a flurry of investigations in the waning days of the Trump administration seeking to uncover whether the district — alongside school systems in Seattle and Fairfax County, Virginia, as well as the Indiana Department of Education — failed to serve disabled students during the pandemic.

The inquiries, announced January 12, just days after former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos left her post, reflect the anguish of those forced to watch their children regress at home, losing skills it took them years to build. Parents from coast to coast say their local school districts should either open their doors to these students or play a greater role in providing at-home care.

“We have heard similar complaints from all across the country,” said Denise Stile Marshall, head of The Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates, Inc., a group that fights on behalf of children with disabilities. “Many parents are desperate and at their wit’s end. It’s been 10 months of getting nothing or going round and round with the district for even the basics…and getting nowhere.”

Four investigations

The civil rights office, in a letter to the Los Angeles school system, cited “disturbing reports” about possible discrimination against disabled children, noting that some students’ parents had already sued the district.

More than 67,000 children in LAUSD receive special education services, a tiny fraction of the national total of more than 7 million.

At issue, at least on the part of some L.A. parents, is the district’s decision to remain closed.

Lisa Mosko, director of special education advocacy for the L.A.-based group Speak UP, which urges parents to fight for equity in their local schools, understands her county is in a difficult position because of a recent surge in COVID cases.

Even so, she said, LAUSD could make a greater effort to curb learning loss during the shutdowns.

“I need to see more urgency when it comes to the district and the teachers union,” said Mosko, who wishes the school system would connect families with behavioral aides who could work with them at home. “They need to be thinking more creatively about how they can really lift kids up during this time.”

School officials stand by their decision to remain shuttered as the virus continues to spread.

“Because of the dangerously high level of COVID-19 cases in Los Angeles County, the Department of Public Health ‘strongly recommended’ on January 8 that all school districts in the County suspend in-person services until the end of the month,” a district spokeswoman said in response to the investigation.

On the other side of the country, Fairfax County Public Schools, which serves more than 28,000 students with disabilities, has asked federal investigators for more information about the allegations that prompted their inquiry and may conduct its own.

So far, a spokeswoman said, it has not been provided with additional details beyond the office’s claim that while the school system declined to provide in-person instruction for students with disabilities, it opened schools for in-person child-care for general education children.

Some parents have spoken out against its local teachers union, which have recently pushed for delays in re-opening.

The education department told Indiana officials it was “particularly troubled” by complaints alleging disabled students “have been forced by local school districts into virtual learning programs that were not individualized to meet those students’ unique needs.”

Kim Dodson, chief executive officer of The Arc of Indiana, which advocates for those with developmental and intellectual disabilities, said services are inconsistent from one campus to the next.

“Some schools figured things out and things went relatively well,” she said. “In other areas it seems that schools have thrown up their hands and are just trying to ride out the pandemic.”

More than 180,000 children in the state are identified as having a disability.

In Seattle, the district was rocked last fall by a jaw-dropping statistic: Only one student was receiving in-person special education services at the end of October compared to hundreds in neighboring districts.

The school system, home to more than 8,000 children with disabilities, was called out for allegedly telling its special education teachers “not to deliver specially-designed instruction,” prohibiting them from adapting lessons to meet each child’s needs.

District officials said they are trying to keep pace with changing requirements.

“Since March, every time state guidance has changed, the district has adjusted,” said spokesman Tim Robinson.

‘Parents have enough on their plates’

The education department said the initiation of the investigations does not prove these school systems are in violation. Investigators are simply trying to determine if these students were denied the free appropriate education to which they are entitled to under federal law.

Stile Marshall said the action is long overdue. She said, too, that it’s important for the department to be proactive in protecting students’ rights.

Her organization has fielded numerous complaints from parents since March, many focused on schools’ failure to implement their child’s individualized learning plans: In some cases, she said, districts are unilaterally changing the amount of hours of related services these students are entitled to receive.

Even more troubling, she said, some children with disabilities have been kept out of distance learning entirely.

“Parents have enough on their plates right now,” Stile Marshall said. “They don’t need to once again fulfill the enforcer role, too.”

But that’s exactly how Stacy Hayes of Bloomington, Indiana, felt when she advocated for her 16-year-old son Mason, who has Down Syndrome and autism.

A significant portion of Mason’s education focuses on life skills, such as ordering food at a restaurant, visiting the grocery store, and using a communication board — in this case, an electronic device that helps him relate his thoughts to the outside world — none of which can be taught through distance learning, his mother said.

To complicate matters, Mason transitioned to a new school this fall. Because of the shutdowns, he was not able to visit the campus or meet with his new teachers prior to starting the ninth grade.

His mother wanted his school to either bring him back to campus safely or help pay for additional services at home.

“He has a short attention span,” she said. “He can only sit in front of a computer for a few minutes, depending what is going on on the screen. Virtual learning is no learning at all.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)