Fearing Special Ed Lawsuits, These New Jersey School Districts Asked Parents to Sign Away Their Rights in Order to Get Services During Pandemic

Updated May 2

In a memo after this story was published, the New Jersey Department of Education notified school districts that requiring parents to waive legal rights in order for their children to receive special education services violated federal law.

Despite widespread disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic, the agency reiterated districts’ legal obligation to provide special education services “to the greatest extent possible.” Requiring families to waive “present or future” legal claims in order to receive special education services “is prohibited,” the education department said.

Fanny Ochoa felt lucky. After campuses closed nationwide due to the coronavirus pandemic, her children made an abrupt transition to learning online — a change she knew would be difficult for both students with disabilities and the schools educating them. Yet despite the turmoil, she felt the district in Clifton, New Jersey, rose to the challenge of educating her two children, both of whom have special needs.

Then the liability form dropped in her inbox.

In order for her children to receive online special education services like speech therapy, the Clifton district asked Ochoa to sign a document that would “fully release and discharge” the city’s schools from “any and all” liability — broad legalese she worried could come back to bite her children if she signed. With school leaders across the country worried that the challenge of providing tailored special education during the pandemic could open them to lawsuits, numerous New Jersey school districts asked parents to sign similar forms in order for their children to receive services. Disability-rights groups say the actions run afoul of federal special education law.

The document left Ochoa feeling like “a deer in the headlights,” she said. She feared that signing the document would leave her without legal recourse against the district if her children fell behind due to school closures. So she refused.

Under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, schools are required to offer a “free, appropriate” education to the roughly 7 million K-12 students with special needs. The law doesn’t address how schools should respond during the unprecedented campus closures, and some education leaders have called on Congress to waive aspects of the rules until schools reopen. On Monday, the Education Department reassured parents that it would not seek waivers on the law’s “core tenets,” but it requested that Congress consider “flexibilities on administrative requirements.”

“There is no reason for Congress to waive any provision designed to keep students learning,” Education Secretary Betsy DeVos said in a news release. “With ingenuity, innovation and grit, I know this nation’s educators and schools can continue to faithfully educate every one of its students.”

When campuses nationwide shuttered, some school leaders opted to halt formal instruction for all students because they couldn’t equitably educate children with disabilities, many of whom require intensive therapies. Fear of legal liability is a legitimate concern for district leaders, said Wendy Tucker, senior policy director at the National Center for Special Education in Charter Schools. But district leaders who focus too much on reducing legal risk — at the expense of maintaining positive relationships with families — could be more likely to face lawsuits than those who work collaboratively with parents.

“It is a lot harder to sue someone you like and respect and you believe is doing right for kids,” Tucker said.

The forms, the existence of which was first reported by HuffPost, were utilized by schools in at least three New Jersey districts, according to parents and advocates: Ringwood, Clifton and Livingston. Officials in those districts didn’t respond to requests for comment.

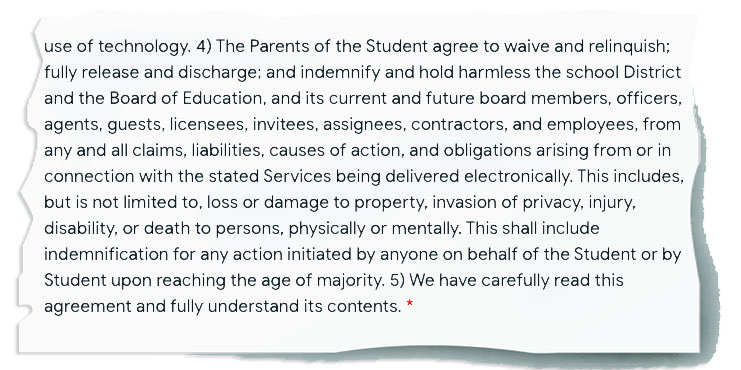

Several waivers obtained by The 74 contain similar, often identical, language. One form, distributed by Ringwood, asks parents to agree not to record online therapy sessions and to ensure that children will follow the district’s technology policies. By signing, parents would agree to “hold harmless” education officials and district contractors from any legal claims related to the services, including “loss or damage to property, invasion of privacy, injury, disability, or death.”

Renay Zamloot, who has worked as a New Jersey-based special education advocate for more than 25 years, said she’d never seen forms like this. Though liability waivers are a common feature of court settlements, this was the first time she’s seen them used as a condition for students to simply receive special education services.

Provided a copy of the form, attorney Miriam Rollin, a director at the National Center for Youth Law, was flabbergasted. “When I went parasailing, I signed a waiver and it looked just like that,” she said. “It’s the waiver that ‘No matter what — you could be beheaded and it could totally be our fault — but you cannot come against us.’”

For many parents, the pandemic has brought illness, job loss and housing instability. Asking parents to sign broad liability waivers at this moment runs counter to federal special education law, she said, which demands collaborative partnerships between schools and families. But at a moment of desperation for many, some parents may simply sign without recognizing the consequences.

The feud

The use of the forms ignited a public feud between two New Jersey-based legal groups.

In a letter to New Jersey’s governor and education commissioner, the nonprofit Education Law Center called on lawmakers to forbid schools from requiring parents to sign liability waivers to get remote special education for their children. Such forms, the group said, “can be interpreted as eliminating future claims” to compensatory education, and this “flies in the face” of special education law.

But attorneys at the Machado Law Group, which represents some 30 New Jersey school districts, see it differently. In a rebuttal letter to state officials, Machado attorneys said their firm likely wrote the form in question — and encouraged districts to distribute them to families. Prohibiting districts from distributing the forms could “provide parents with a false sense of security and leave school districts liable for things beyond their control.”

The firm didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The Machado letter said such forms sought to inform parents about the “inherent risks” of online instruction, including implications for student privacy and digital recordings that the firm said could run afoul of the state’s wiretapping law.

Parents should be aware that speech or occupational therapy conducted online could cause physical injury to students if “directed incorrectly,” the group said. While the liability forms outline such risks, the group said, attorneys brushed off claims that signing would leave parents without recourse to make-up services once campuses reopen.

In a statement, a state education department spokesperson said the agency is “actively monitoring this to ensure that all students receive the services they need in a safe and comprehensive manner.” The governor’s office didn’t respond to a request for comment.

‘Don’t sign it’

Ochoa, of Clifton, doesn’t want to create an adversarial relationship with the city’s school district. But the liability form has her considering her options, including mediation or litigation.

After she declined to sign the document and outlined her concerns, she received a letter from district special education officials. If she refuses to sign but her children still receive online services, their participation “will be considered your acknowledgement and acceptance” of the risks, officials wrote. The letter led Ochoa to weigh the risk of signing against withholding therapy from her children.

“I don’t know how to take that,” she said. “I’m still processing that letter.”

When a New Jersey mother sent her a liability form and asked how to proceed, Zamloot instructed her to grab a Sharpie and black out the language she found objectionable. For the one parent, the simple solution worked. The district accepted the amended form and provided services, she said.

But Rollin of the National Center for Youth Law offered even simpler advice:

“Oh God, don’t sign it.”

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)