Philadelphia and Other School Districts Resisted Transition to Online Instruction Over Equity Concerns. Advocates Say Children With Disabilities Were ‘Scapegoated’

Despite the pounding rain and a tornado watch one recent Monday morning, Anna Perng stood in a line that wrapped around her son’s elementary school in South Philadelphia. Huddled along the side of the brick building, she struggled to keep six feet of distance between herself and other parents, many of whom lacked umbrellas, let alone face masks.

The situation made Perng feel unsafe, especially after crossing paths with a fellow parent who had an uncontrollable, wet cough. But she felt she had no choice: She needed to pick up a school-issued Chromebook for her 7-year-old son Ethan, who has autism.

After the Philadelphia school district closed its campuses March 16 as the coronavirus pandemic spread across the country, Ethan and the other children enrolled in the city’s public schools went more than a month without formal instruction. Instead, the district made online learning strictly optional. Because the schools couldn’t adequately educate all children, including those with disabilities, district officials said they wouldn’t provide formal instruction to anyone.

While districts across the country transitioned to teaching online, Philadelphia was one of many that resisted the change. School leaders presented the issue as one of educational equity, but parents with special-needs children felt they’d been “scapegoated,” said Maura McInerney, legal director at the nonprofit Education Law Center-PA.

The federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act requires the nation’s schools to provide tailored instruction to the roughly 7 million K-12 students with special needs. But no one could have predicted the current reality, in which the circumstances of the pandemic require students across the country to be taught remotely, typically through online instruction. Some education leaders say it’s simply impossible to serve all children with disabilities equitably since many require intensive — and often hands-on — therapy. For that reason, the pandemic seems bound to put America’s school systems on a collision course with the law.

Initial guidance from the U.S. Department of Education led many districts to make online learning optional to avoid special education mandates. But pressure from local advocacy groups — and stern comments from Education Secretary Betsy DeVos — caused school leaders in Philadelphia and elsewhere to pivot. After buying 50,000 Chromebooks and distributing them to students, the Philadelphia district began formal online instruction Monday.

The walkback doesn’t mean that states and districts will avoid having to settle many of these issues in court. Some education leaders are now calling on federal lawmakers to waive aspects of the federal education law until campuses reopen. The $2.2 trillion coronavirus stimulus law passed last month gave DeVos until the end of April to explore whether districts need relief from the law during the pandemic.

In a letter to federal officials, the National Association of State Directors of Special Education requested that districts get “temporary and targeted flexibility” on student evaluations, funding requirements and other procedures. Valerie Williams, the association’s senior director of government relations and external affairs, said such waivers would likely have little effect on students.

“Providing waivers for the civil rights of students with disabilities, we don’t take that lightly,” she said, but extensions and relief on some requirements is necessary given the difficult circumstances.

In the meantime, the monumental task of educating children with disabilities during the pandemic has led to wide variation between states, districts and individual schools. Perng has seen it firsthand.

She contrasts the frustrating experience she’s had with Ethan at Stephen Girard Elementary School in Philadelphia with that of her 9-year-old son, Sam, who also has autism. Sam attends a private school in New Jersey that is geared toward students with disabilities. Officials at the school moved quickly when concern over the virus ramped up, she said, and since the campus closed, they have provided individualized instructional materials while keeping in touch with families.

But the ordeal of getting Ethan a Chromebook has only intensified Perng’s years-long rocky relationship with the Philadelphia district over its special education services. Now, with the confusion and frustration that accompanied the instructional lag, she accuses the district of inadequately considering her son’s needs.

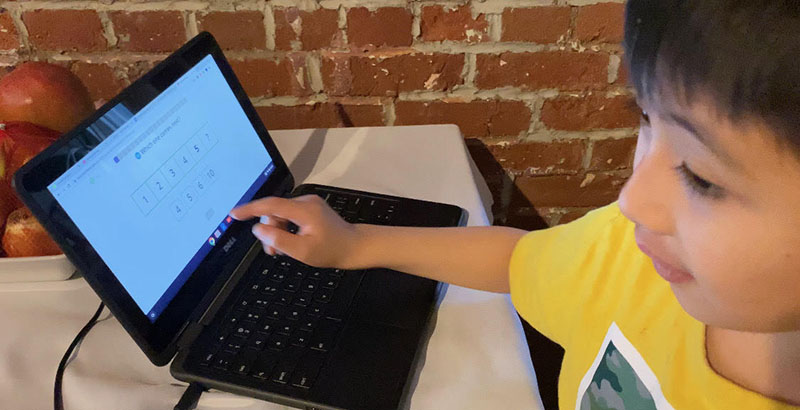

Perng understands that the transition to online learning is difficult for both educators and students. Yet when she got the Chromebook, she found the school’s recommended activities on it to be developmentally inappropriate for Ethan. That has exacerbated significant technology hurdles. Because of the kindergartner’s disability, he’s unable to use a traditional laptop. The school-issued Chromebook has a touchscreen, which Ethan’s special education teacher hoped would make online materials accessible, Perng said. But when she logged into a math activity on the Chromebook, the unfamiliar device made Ethan upset, so they had to stop.

The Philadelphia district didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Thinking about how the virus-induced campus closures could affect Ethan’s educational progress brought his mother to tears.

“It’s devastating to know how hard I and other families — and even their [special education] teams — have worked for years to get our kids where they are today,” she said. “To see all of that potentially be lost in a matter of days or weeks and now months, it keeps me up at night.”

‘Serious misunderstanding’

Disability-rights advocates lay much of the blame for the confusing rollout at the feet of the federal education department, which has released evolving statements on the issue.

Last month, in its first guidance on serving children with disabilities during the pandemic, the department said that if districts provide educational opportunities to the general student population, they must ensure that children with disabilities have equal access. But if they closed outright, the guidance said, districts weren’t required to provide special education.

Denise Marshall, executive director of the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates, said the guidance led some education leaders to “throw up their hands” and simply close schools rather than figure out how to educate children with disabilities.

State education leaders in Pennsylvania and elsewhere interpreted the federal department’s message as letting districts off the hook for special education. Across the country in Oregon, for example, officials instructed schools to offer “supplemental education and learning supports,” rather than formal instruction, and therefore did not require them to provide special education. Under that strategy, state officials wrote, no students were to be “specifically instructed towards new learning goals.”

About a week after unveiling its initial guidance, the federal department took issue with such measures, pinning them on a “serious misunderstanding.” School districts should not cite federal special education laws to withhold distance learning opportunities to students, including those with disabilities, the department said. In a sharp critique, DeVos blasted school districts that used department guidance “as an excuse not to educate kids.”

Those statements led many states and districts, including in Pennsylvania and Oregon, to backtrack. But not everyone changed their approach. In Iowa, for example, remote education remains optional, with most districts opting to offer “voluntary educational enrichment opportunities.”

Despite DeVos’s forceful language when the department released its latest guidance, disability-rights groups remain worried that Congress could waive special education rules.

Among those calling for federal flexibility is Daniel Domenech, executive director of AASA, The School Superintendents Association. While some school leaders fear they could face lawsuits for failing to provide adequate special education services, he said during a recent webinar that the updated federal guidance “provides no cover at all.”

“We’re not looking for anything permanent, just short-term flexibility that recognizes the situation that exists today,” he said, adding that he wants waivers for administrative procedures like developing individualized plans for children with disabilities. “Where there are procedures that involve physical involvement and presence, that can’t be done.”

But for disability rights advocates, the thought of waiving aspects of a hard-fought civil rights law, even temporarily, is nerve-racking.

“This is not the time to be abandoning the rights of students with disabilities,” McInerney said, adding that the pandemic could come with negative ramifications for many children with special needs. “Parents of students with disabilities are in an exceptionally vulnerable position during this time because they desperately want their children to receive educational services and are rightfully concerned about regression.”

Embracing the challenge

As schools nationwide shift to online learning with unprecedented speed, some leaders have embraced the need to teach children with special needs despite the trying circumstances.

At Kingsman Academy Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., where roughly 40 percent of pupils are disabled, students took a weeklong spring break when the campus closed last month. Educators used the time to craft a distance learning plan, said Shannon Hodge, the school’s co-founder and executive director.

Though the transition hasn’t been easy, she said that complying with federal special education laws isn’t her primary concern. She pays little heed to the threat of lawsuits from families with special needs children. Instead, she said, schools must focus on reaching each child as best they can during a period of widespread disruption.

“It’s not a point of pride for us to say we have a compliant program,” Hodge said. “We want to make sure we’re making the most for all students, including those with” disabilities. “For many people in many jurisdictions, the primary focus has been on complaints under the label of equity. They’re saying that if it’s not equitable, they can’t do anything. Our approach is that school isn’t closed.”

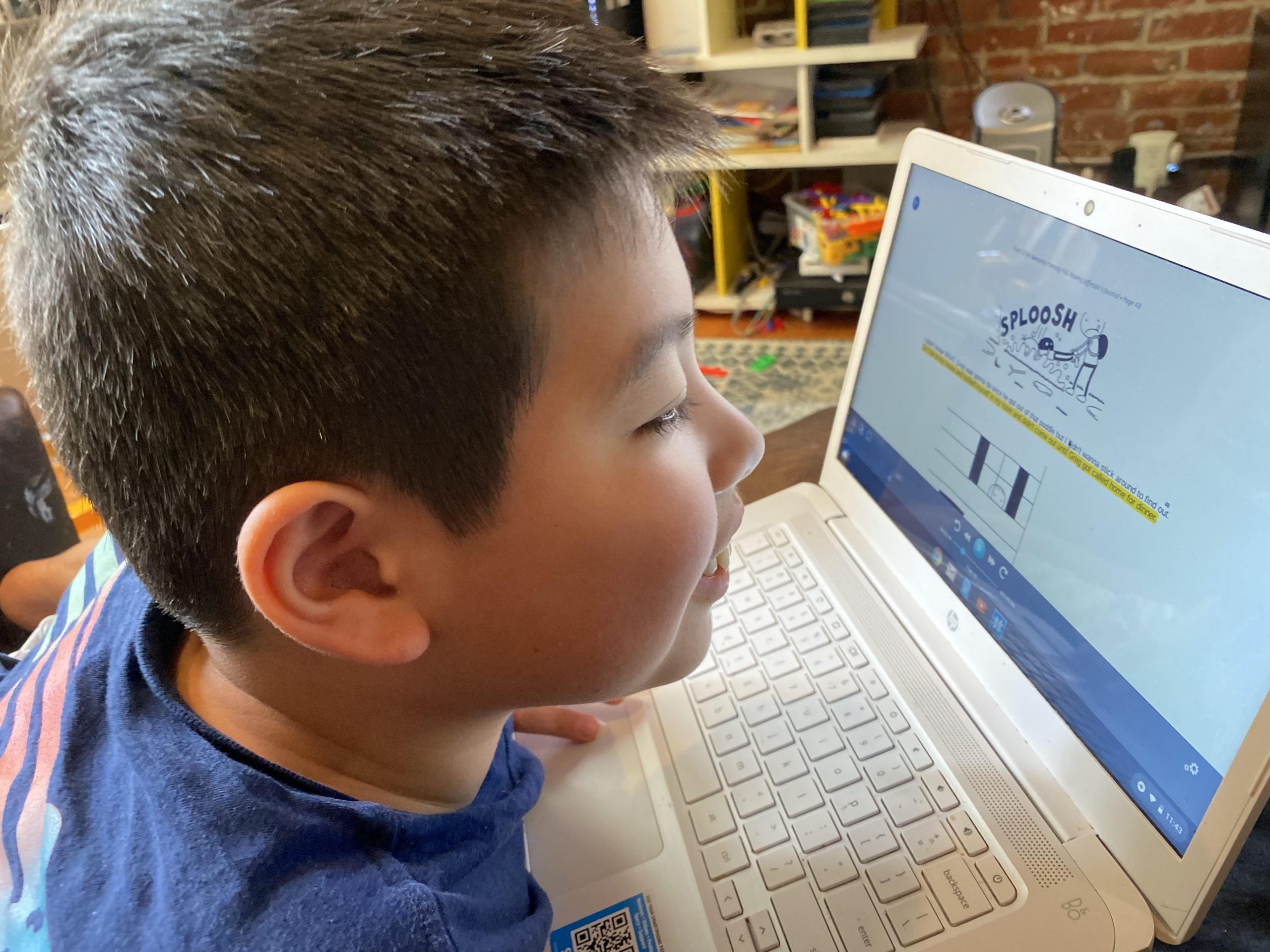

The transition has also been trying for teachers. Christine Montera, who teaches 11th-grade history at East Bronx Academy in New York City, said educational setbacks among her special needs students is a major concern. But for several of her students with disabilities, the school’s transition to online learning has actually been positive. In fact, the change has made her think harder about ways to individualize teaching for each student.

One of her students has long struggled to complete assignments in class because it takes him longer to process information while reading and listening because of his learning disabilities, Montera said. Now, he’s completing all of his assignments in the remote setting, she said.

Within-state variation

For parents like Perng, the current reality has meant advocating for her kids while trying to make the best of a tough situation. It’s a dilemma parents of special needs students are used to.

So far, the experience of her older son, 9-year-old Sam, has been positive. When he struggled at his public elementary school in Philadelphia, she sent him to a private school in New Jersey that serves children with disabilities. Even before Orchard Friends School closed due to the pandemic, she said, Sam got a packet of instructional materials.

“It wasn’t a one-size-fits-all ‘Here’s a packet, good luck,’ she said, adding that the materials were tailored to Sam’s needs. “They’ve been really supportive in helping families transition to this homeschooling.”

At the state level, New Jersey education officials emphasized from the start schools’ obligation to educate children with disabilities during the pandemic, said Elizabeth Athos, senior attorney at the New Jersey-based Education Law Center. In early March, state officials instructed schools to craft plans for remote instruction, including for students with special needs.

“There wasn’t a question from the beginning; it was clear that students with disabilities had to be served — and that all students had to be served,” she said.

Amid the transition, the state board of education — in a virtual meeting — revised its special education rules to ensure that schools can offer teletherapy for children with disabilities. The regulatory change allows districts to provide services like speech therapy online during the pandemic.

In Pennsylvania, where school funding disparities between wealthy and low-income districts are among the nation’s highest, the transition to online learning has been predictable, said Jeannine Brinkley, executive director of the Parent Education and Advocacy Leadership Center. While better-resourced districts had the technology and staff to transition quickly, she said, low-income districts like Philadelphia were less prepared. As Philadelphia parents with disabled children waited for formal instruction to begin, it was frustrating to see neighboring districts offer more to their students, Brinkley said. Despite the beginning of formal online instruction Monday, the district doesn’t plan to teach students new material until next month.

Inconsistencies also exist within the Philadelphia district, Perng said. She’s been communicating regularly with other parents, and while some “feel like they’re plugged in” and are having great experiences, families with special needs children “feel like they’ve just been cut off.”

As students in the city began formal online instruction, Perng felt as if it became her responsibility to provide intensive special education to her son. Ethan’s teacher created a series of videos outlining how parents could teach their children, but soon realized the idea wouldn’t work out as planned. Meanwhile, Ethan has yet to receive speech therapy online, even though the service is one of the most critical components of his education, Perng said.

Though Ethan’s teacher is trying to make the best of the current situation, Perng said inconsistent leadership from the district has put both parents and teachers in a bind.

“As much as I feel like I’m on an island,” Perng said, “I think that the teacher is also on her own island.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)