Behind the Looming L.A. Teacher Strike, Crippling Long-Term Debt That’s Left the City Little Room to Negotiate — and May Ultimately Doom the District to State Takeover

The looming teacher strike in Los Angeles, no matter how it’s sliced, comes down to money — but not the salary raises and cost of new hires that have kept the district and its teachers union apart during nearly two years of contract negotiations.

The real money problem, experts say, lies with the district’s skyrocketing long-term debt.

Experts warn that for the district to stay out of bankruptcy, it must slash its billions in long-term liabilities, much of it tied to massive retiree health benefit costs.

Their prescriptions ranged from making employees and retirees pay premiums to offering early retirement incentives. Most agreed that a local solution is needed to right the ship as California faces — or could already be in — a recession, meaning state taxpayers may be unable to bail out the district.

But United Teachers Los Angeles has rejected the district’s proposal to shave off costs by adding two years to how long it takes new employees to become eligible for free lifetime health benefits — something other L.A. Unified unions have already accepted. Union officials dispute the district’s claim that it is cash-strapped, saying it is “hoarding” nearly $2 billion in reserves.

L.A. Unified’s full contract offer includes a 3 percent teacher salary raise retroactive to last year and 3 percent for this year. The district has also offered $105 million next school year toward UTLA’s demands for lower class sizes and more nurses, counselors, and librarians, and officials met Wednesday with California state legislators to “advocate for a larger investment in public education.” UTLA, which represents more than 30,000 educators and other district employees, has offered concessions too, but union officials said L.A. Unified’s contract offer is still “a drop in the bucket when it comes to our students’ needs.”

A court ruling Thursday cleared the union to begin its strike on Monday. Both sides said last-ditch talks may continue through the weekend. It would be the first L.A. teacher strike in 30 years and would affect more than 480,000 K-12 students across more than 1,000 schools.

“If you’re the union, your job is to argue for more benefits for your members,” said Andrew Crutchfield, director of the political philanthropy network Govern for California. But, he added, “I think there’s some legitimate questions [as] to what degree the union is representing the interests of current workers.”

A health care plan L.A. Unified ‘can’t afford to pay off’

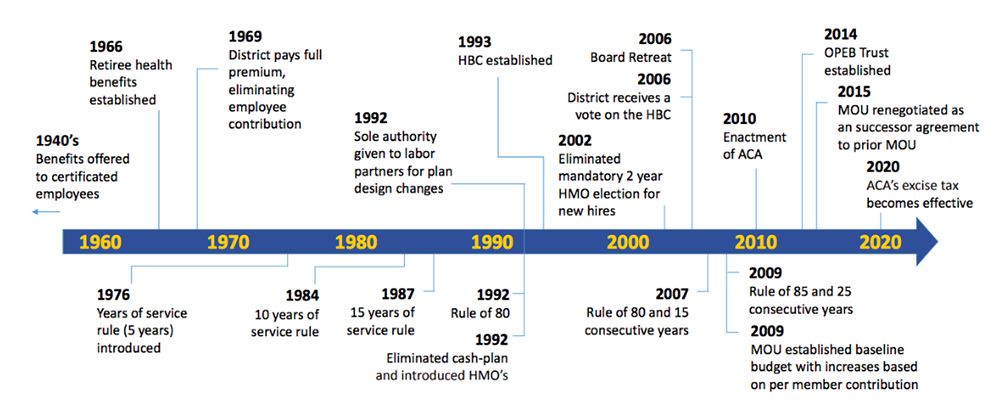

L.A. Unified’s proverbial “fiscal cliff” has been years in the making and is the fault of the district and political leadership, Crutchfield said. While other public school systems across California are also facing insolvency, L.A. Unified dug itself a deeper hole beginning in the late 1960s, when it started granting eligible employees, retirees, and their dependents free lifetime health benefits — including full medical, dental, and vision — without requiring them to contribute to the cost. Retiree health benefits alone are costing the district a projected $314 million in 2019.

The district, stated simply, has a health care plan it can’t afford to pay off, said Chad Aldeman, a senior associate partner at Bellwether Education Partners. “LAUSD has valued their retiree health promises at $15.2 billion but [has] only saved $244 million,” Aldeman said.

Money that could be spent in the classrooms is therefore being siphoned off. The $314 million cost of retiree health benefits is equivalent to about $12,500 in district spending annually per teacher, Aldeman said. “That’s money that’s not going to teachers, either through salary increases or hiring new teachers.”

From 2001 to 2016, LAUSD increased:

– Overall spending by 55.5%

– Spending on salaries and wages by 24.4%

– Employee benefit spending by 138% pic.twitter.com/sprEG74EHZ— Chad Aldeman (@ChadAldeman) January 7, 2019

L.A. Unified’s health care benefits package — which school board member Nick Melvoin has called one of the most generous in the country — eats up about $2,300 of the $16,000 the state paid L.A. Unified in 2018-19 for every student it serves.

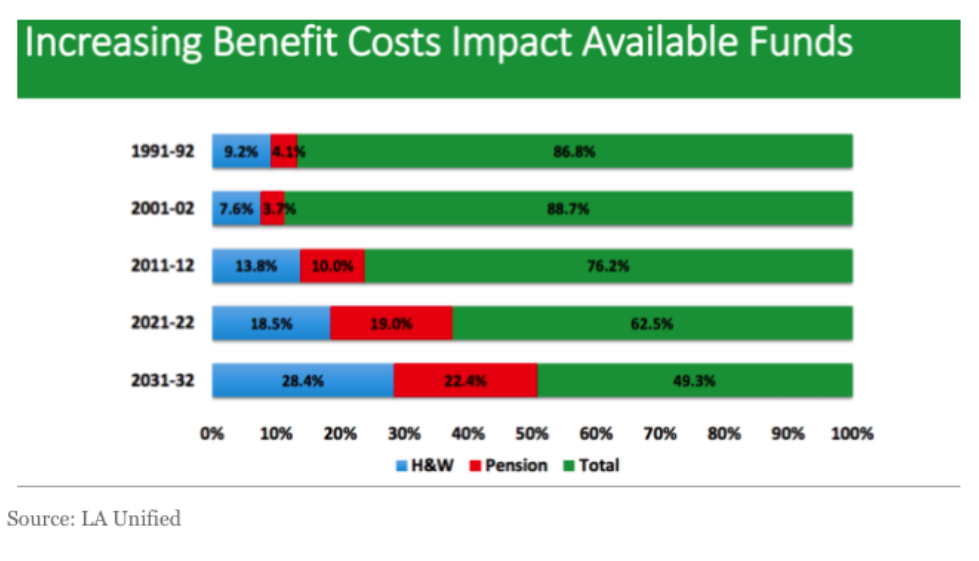

By 2031-32, the district estimates that half of L.A. Unified’s budget, which was $7.5 billion this year, will be spent on health care and pensions. Part of that is out of L.A. Unified’s control: All California school districts are facing higher employer pension contribution rates — rising from 8.25 percent in 2013 to 19.10 percent in 2020.

Health care benefits for retired employees are determined by a local Health Benefits Committee. But of its nine members, only one is a district representative; the remaining eight represent each of LAUSD’s various employee unions.

This setup, which “essentially means the district can’t control its health care benefits,” is fairly unique to L.A. Unified, Crutchfield said. “[It’s] kind of madness.”

Health care benefits are negotiated separately at L.A. Unified from the salary and workplace conditions now at issue in the pending strike. A three-year health benefits contract was approved last spring, so the next opportunity to negotiate them won’t be until 2021, when the district is expected to already be running a deficit. The unions did agree in last spring’s benefits contract to use a reserve fund to cover increases in health care costs, which are projected to rise 6 percent this year.

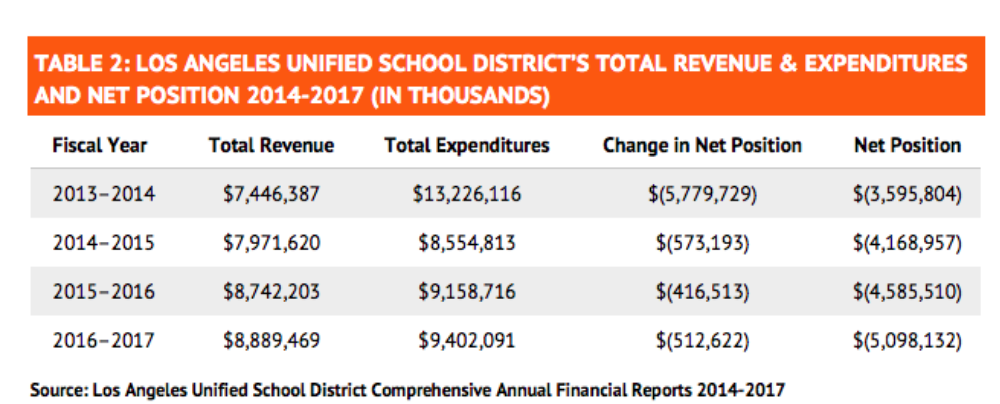

Over time, these long-term obligations have contributed to what is now a $19.6 billion unrestricted net deficit — “obligations that a district must pay out in future years using future district revenue,” which would take away from “things such as teacher salaries and supplies,” Aaron Garth Smith, an education policy analyst with the right-leaning Reason Foundation, explained.

To put that number in context, it would take $4,140 from every woman, man, and child in L.A. Unified to erase the deficit, state Sen. John Moorlach wrote in a December op-ed for the Los Angeles Daily News.

Considering its long-term debts, “LAUSD doesn’t have two nickels to rub together,” Moorlach told LA School Report. His research ranked the district’s per-person contribution cost as one of the highest among California’s 944 public school districts.

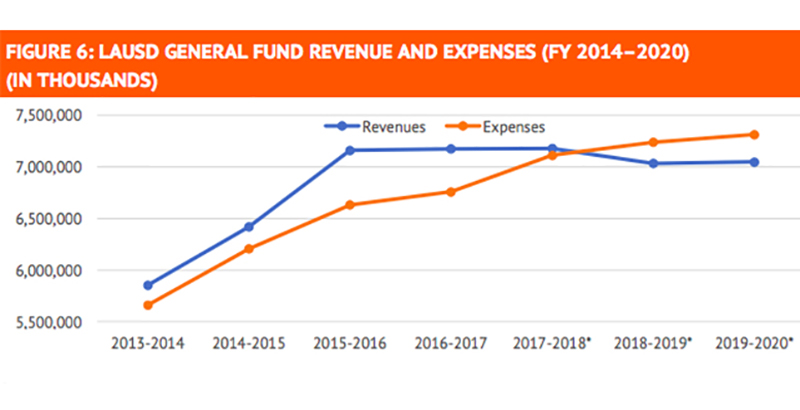

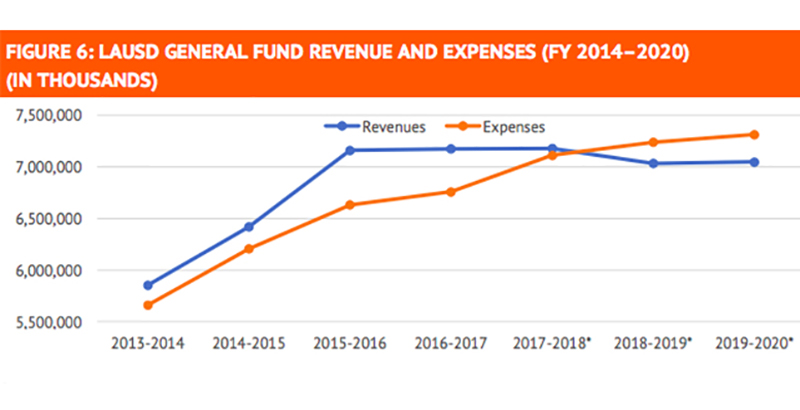

That reality is especially “crazy,” Crutchfield noted, when considering that the district received increased funding from the state over the past four years.

The state’s school funding mechanism — the Local Control Funding Formula — was rolled out in 2013, generating over $1 billion a year in district revenue, a Reason Foundation study reported. That annual boost in funding is now winding down, however.

“The alarms should be sounding,” Crutchfield said.

Aldeman said the district’s attempt to shift the lifetime benefits eligibility back two years is a small step in the right direction, adding that another solution — though it would require agreement by the unions — could be to have employees, retirees, and dependents start paying premiums. He added that having retirees “with moderate incomes” get health care coverage through Obamacare or Medi-Cal, California’s version of Medicaid, should be on the table as well.

“The district should not be a health care provider when there are either statewide or national solutions that could take a lot of the [financial] risks off the table for the district,” he said.

Righting L.A. Unified’s financial ship

Most experts interviewed agree that the responsibility largely lies with the district to fix the financial picture, though.

To that end, L.A. Unified in November announced a 15 percent reduction to its central office this year and next, saving an estimated $86 million. The school board and state voters have also green-lighted a 2020 ballot measure to bolster statewide education funding — but even if voters pass it, it would roll out just as the district projects that it will become insolvent. Board members this month passed a resolution directing the superintendent to develop a three-year plan to increase district revenues, which could include a parcel tax, school bonds, and property tax reform.

Moorlach also recommended offering early retirement incentives — though when a San Diego-area school district board voted in December to do that, it prompted the San Diego County Office of Education to take away its decision-making control.

“You see who you can encourage to leave, maybe a year or two or three before when they wanted to,” he said. “There’s a cost to that, but maybe you can fill in those vacancies with newer, younger teachers [who are paid less].”

UTLA teachers are paid an average base salary of $70,141, with an additional average $14,562 in health and welfare benefits, a district spokeswoman told LA School Report. The state average base salary was $77,179 in 2016-17.

Center for Education Reform CEO Jeanne Allen is one expert who thinks state involvement will be inevitable, however.

“[L.A. Unified] could be radical and innovative: They could break up schools, they could try to create new schools, they could close schools; but fundamentally, if they don’t change the way they hire, retain, reward, or pay educators, there’s not going to be a lot of change,” she said. “The district could do that, but they’re not going to. … There’s too many moving pieces. Too many vested interests.”

Those vested interests are why the district and union can’t even agree on where the district stands financially.

Accepting all of UTLA’s demands, which include a full-time nurse in every school and more special education teachers, would add $813 million each year to the deficit and wipe out L.A. Unified’s reserves this school year, the district has said.

“If we had said yes” to all the union’s demands, “we would be bankrupt right now. We’d be under state receivership,” L.A. Unified Superintendent Austin Beutner told Speak Up in August.

L.A. Unified says it’s spending about $500 million more a year than it’s taking in, and the county estimates the district’s reserves will drop from $778 million this year to $76.5 million in 2020-21.

County and state officials warned L.A. Unified in the fall that they would step in and take over if reserves dip too low. The county Office of Education took that first step Wednesday, appointing a team of fiscal experts charged with helping L.A. Unified craft an updated Fiscal Stabilization Plan by March that would aim to bring the district’s 2020-21 reserve projections to 1 percent or more of its expenditures, County Superintendent of Schools Debra Duardo told LA School Report on Thursday.

Experts “will be in there hands-on,” she said. “We don’t have the authority to tell LAUSD how to spend their money; at this point, we’re just going in as collaborators, as people with real financial expertise … [who] can help them come up with a clear plan.” The fiscal experts will start working with the district full time as soon as next week, she said.

A more severe next step by the county — which could feasibly happen in March or earlier, Duardo said — would be to install a fiscal adviser, who would have what’s known as “stay and rescind” powers. That person would essentially take over all financial decisions, taking away control from L.A. Unified’s superintendent and school board.

The final step would be state takeover, which happened in neighboring Compton in 1993 and Inglewood in 2012.

UTLA continues to dispute the district’s statements about its finances, however, pointing out that L.A. Unified has been wrong in the past about how soon it would run out of money. The district’s 2016 budget, for example, projected it would run out of cash by this year. The union also believes the district is “intentionally starving our schools,” hoarding nearly $2 billion in reserves “so that cuts can be justified.” L.A. Unified had about $1.86 billion in reserves at the end of the 2017-18 year, but it maintains that the bulk of that money has been designated for teacher salary raises, funding for at-risk students, debt payments, and other expenses.

Jaime Regalado, professor emeritus of political science at California State University, Los Angeles, said he understands UTLA’s skepticism with district leadership’s data and propositions.

“I don’t think any school district [administration] over the past score of years has ever been entirely truthful,” he said.

He added that while he recognizes the need to have a reserve, “if I’m a teacher and in with the kids and seeing that my class size has expanded, I’m not getting much help with teacher aides, I’m still paying out of my own pocket for certain things … then I really understand that as well.” Class sizes can climb into the 40s.

Aldeman believes district politics play a role in the current divide. “There’s a lot of education that needs to go on in terms of educating UTLA members about what the actual situation of the district is and what are the drivers of that, and how to get out of that [fiscal] hole,” he said.

And one particular point, Crutchfield said, needs to hit home.

“Tackling the long-term liability is what needs to be done,” he said. “Other measures, while they may have merit and may save meaningful amounts of money, are somewhat like moving the deck chairs on the Titanic.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)