Exclusive Report: As Movement Grows, Microschools Aren’t So ‘Micro’ Anymore

The spread of private school choice programs are fueling growth, but public schools also see the model’s potential.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

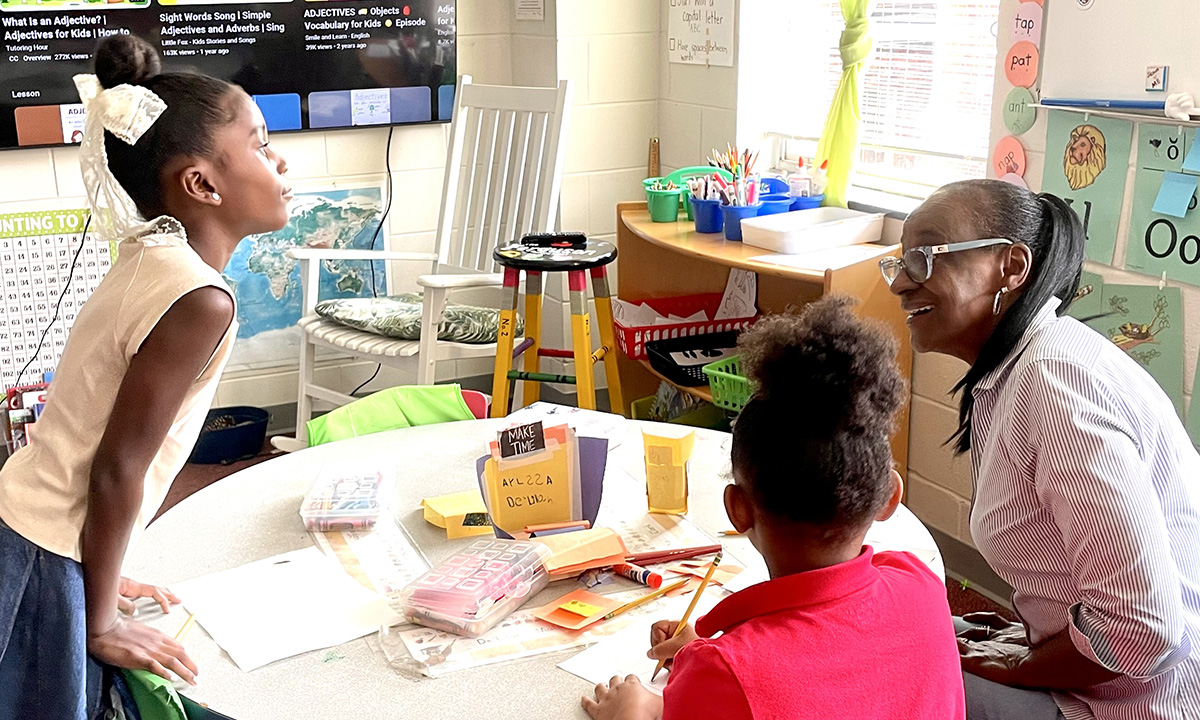

In 2021, Tiffany Blassingame, who comes from a family of educators, opened her own school in a building attached to a Baptist church in downtown Decatur, Georgia. She teaches 18 K-5 students who come from across Atlanta for a Christian-based curriculum with a social justice lens.

But now she’s got company.

Down a hallway lined with artwork, backpacks and storage bins, there’s a small Montessori school for 3- to 6-year-olds. A middle and high school operates on the same floor. And across from Blassingame’s two classrooms, Maya Corneille runs Nia School, which serves children with autism and apraxia, a disorder that affects movement and speech.

“Everyone has their own niche and strength,” said Corneille, a former college psychology professor.

Together they demonstrate how the microschool movement, which took off during the pandemic, continues to grow and adapt to students’ needs.

Microschools are also less “micro” than they were last year, according to the latest analysis of the sector from the National Microschooling Center, shared exclusively with The 74. In 2024, the median number of students in a typical microschool was 16. That figure has jumped to 22 — a reflection of the increased experience of school founders, said Don Soifer, CEO of the center. Some now serve as many as 100 students.

The center’s report provides a comprehensive look at the trend as it continues to mature. Microschools — small schools that typically operate out of homes, commercial spaces or churches — now serve an estimated 2% of the U.S. student population, or about 750,000 students. Current or former teachers, or those with administrative experience, are increasingly running the programs. Eighty-six percent of founders have an education background, compared with 71% last year.

But some aren’t leaving public schools to join the movement. Charter microschools and those affiliated with districts are generally larger, with a median size of 36 students, according to the report.

They include WIN Academy, a project of BridgeValley Community and Technical College in South Charleston, West Virginia. This year, 20 seniors graduated from the charter microschool, where students earn college credit toward degrees in nursing or manufacturing.

“The families we serve just see the huge amount of money they are saving on college tuition and the incredible learning opportunity this is for their kids,” said Casey Sacks, the college’s president. With small groups, real-world experiences and a personalized approach, the school, she said, “exemplifies many of the core elements of microschooling.”

In another development, the Indiana Charter School Board recently granted a charter to a microschool network within the 1,200-student Eastern Hancock district, outside Indianapolis. Superintendent George Philhower expects one to three sites to launch this fall, with more opening across the state in the coming years.

“There’s a growing number of families looking for something in between the traditional public school experience and homeschooling,” he said. “Some are already homeschooling and doing amazing work, but they’re also looking for community, guidance, or access to certified teachers and additional resources.”

‘Financially sustainable’

The vast majority of microschools operate outside the public system, but the expansion of state-funded programs supporting private schools, like education savings accounts, has further fueled their spread. Primer, a for-profit microschool network, currently has schools in Florida and Arizona, and will add schools in Alabama this fall.

Over the next two years, the company plans to add five to six states, said Lisa Tarshis, head of the Primer Foundation, which provides financial aid to families and support to schools in the network. With ESA funds fueling growth, she added that some microschool entrepreneurs are replicating their programs.

“Once you get it down, it’s not that hard to open a satellite campus or to bring on another teacher,” she said. “Then you can become the owner and oversee these two schools.”

Of the 800 schools represented in the center’s survey sample, 38% receive state school choice funds, up from 32% in 2024.

This fall, Blassingame’s Ferguson School could be enrolling students on Georgia’s new Promise Scholarship, a $6,500 ESA targeted to students who live in a zone with a failing school. Others, she said, may qualify for the state’s separate ESA program for students with disabilities.

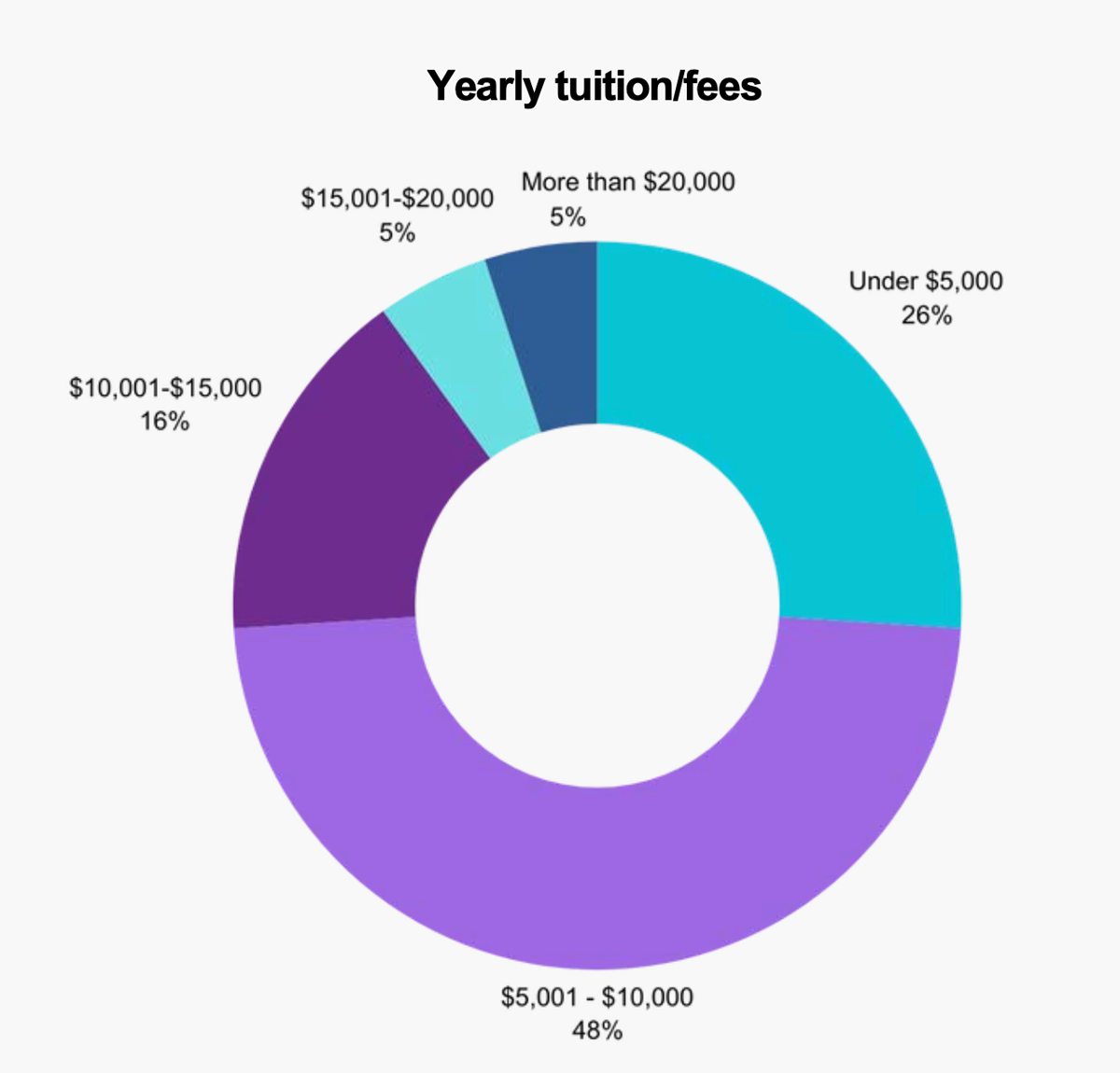

ESAs make microschools “more affordable for parents and financially sustainable for me,” said Blassingame, who is accustomed to offering discounts on her $9,000 annual tuition and working out payment arrangements when families struggle. “I ask, ‘How much can you pay?’ But I have to be able to pay teachers and the rent.”

Democratic critics argue that ESAs not only hurt public schools, but also offer false hope to the 1 in 5 students who attend school in rural areas. Those communities often don’t have private options and the schools that exist may not provide transportation, the left-leaning Center for American Progress argued in a new report.

Microschools, easier to launch than a typical brick-and-mortar school, provide an alternative, said Amar Kumar, CEO of the KaiPod network.

Even choice-friendly states like Indiana and Ohio still have “school choice deserts,” he said at a recent gathering in Atlanta for leaders running “hybrid homeschools,” which often combine microschools with at-home learning. “We can pass as many ESA programs as we want, but until we increase the supply of schools, we won’t really have choice.”

‘Broader than just a reading score’

As more microschools tap public education funding, they’re drawing increased scrutiny from organizations outside the sector. Whether motivated by curiosity or criticism, growing interest from researchers and policy experts is another sign of the model’s expansion.

At least three studies are underway to examine microschools and report student performance on some of the same measures public schools use, like iReady assessments and MAP tests from NWEA.

“There’s a lot of appetite for figuring out how we measure outcomes without being spaces that are tailored 100% towards a standardized test,” said Jeffrey Imrich, CEO and co-founder of Rock by Rock, which sells project-based learning curriculum and materials, primarily to microschools and homeschoolers. The company is working with Mathematica, a research organization, on one of the studies. “There’s an interest in making sure kids are learning and growing, but the interest is in a set of outcomes that is broader than just a reading score.”

But critics warn that the microschools still lack adequate government oversight. In a recent article, the Center for American Progress characterized the unconventional programs as potentially unsafe spaces that often “bypass” building codes and are not required to follow civil rights laws, like the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, even if they receive public funds.

In a rebuttal, Soifer pushed back against the authors’ call for greater accountability and locking into a federal definition of microschools. Founders in this “many-flowers-bloom movement,” he said, already navigate “complex and often arbitrary” regulations designed for large, traditional schools. For example, in March, the Arizona fire marshall told a microschool founder she would have to spend thousands of dollars for building upgrades even though local authorities had already approved the school’s opening. After the libertarian Institute for Justice got involved, the state backed off.

As with last year’s report, founders getting ready to open schools say their number one need is understanding the rules and laws that apply to their programs.

‘Like a four-letter word’

With Texas recently passing a voucher program, Soifer and others are closely watching how the microschool model fares in the nation’s second largest state. Currently, he said, there’s no reliable count of the number of Texas microschools.

“There are just too many that have been doing things under the radar for a long time,” he said.

But if they want to serve students on ESAs, they’ll have to meet the same requirements as other private schools. That means staying open for at least two years and getting accreditation.

Earning accreditation continues to be a costly, and often insurmountable, barrier for many microschools. The process, which typically includes a financial audit, staff background checks and building inspections, can run up to $15,000.

But most accrediting organizations haven’t always been what Soifer calls “microschool friendly.” Less than a quarter of microschools in his survey are accredited, but 80% percent said they would be interested in a process geared toward their non-traditional programs. At least one accrediting body, Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools, recently announced a pilot accreditation program for “innovative school models.”

The issue came up at the Atlanta conference, organized by the National Hybrid Homeschool Project at Kennesaw State University.

“Accreditation is like a four-letter word in this community,” said Sharon Masinelli, a lead science teacher at St. John the Baptist Hybrid School, outside Atlanta. She led a session describing why she sought recognition from Cognia, the nation’s largest accrediting body. High schools, she said, wouldn’t accept course credits for students leaving the hybrid school until it was accredited.

Other microschools seek accreditation so they can accept students on ESAs, just like well-established private schools. Mitch Seabaugh, senior vice president of the Georgia Promise Scholarship, also spoke at the conference, inviting attendees to give their input on the new program.

To Eric Wearne, who runs the Kennesaw project, the moment offered yet another sign that microschools had made it into the mainstream.

Addressing the group the next day, he said, “If you had told me that we would one day have a state official in a room full of school founders asking for advice, I would have lost money on that bet.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)