In Most Microschools, Accountability Is to Parents – Not the Public

New school models use tools like Khan Academy to track student progress, but some critics of private school choice say that’s not enough.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Like many alternative education models, Burbrella Microschool doesn’t fit the mold of a typical school. Housed in a shopping mall space formerly occupied by a Foot Locker and a Radio Shack, the Burlington, North Carolina, program appeals to families whose children weren’t thriving in public schools.

Dominique Bryant made the switch for her 10-year-old after two years of watching him struggle with reading. She first noticed how far behind Malcolm was in second grade when he couldn’t read the instructions on a homework assignment.

“I looked in his face and he just was so defeated. I said ‘I’ve got to do something else,’” she said. Now her two daughters, Ebony and Aviana, attend the school as well.

One way Burbrella stands out in a growing marketplace of unconventional school options is by grouping students of similar ages and learning needs together in pods — a format that a lot of families became familiar with during the pandemic. The school, however, takes a more mainstream approach to measuring how well students learn math and reading. Teachers turn to some of the same assessments still used in traditional public schools, like the Iowa tests to pinpoint students’ skills when they first enroll and i-Ready to monitor progress throughout the year.

“We look for their strengths, their interests, and we integrate that into play, nature and projects — just to really make learning fun — but also to close the gaps they have academically,” said Dominique Burgess, the school’s founder.

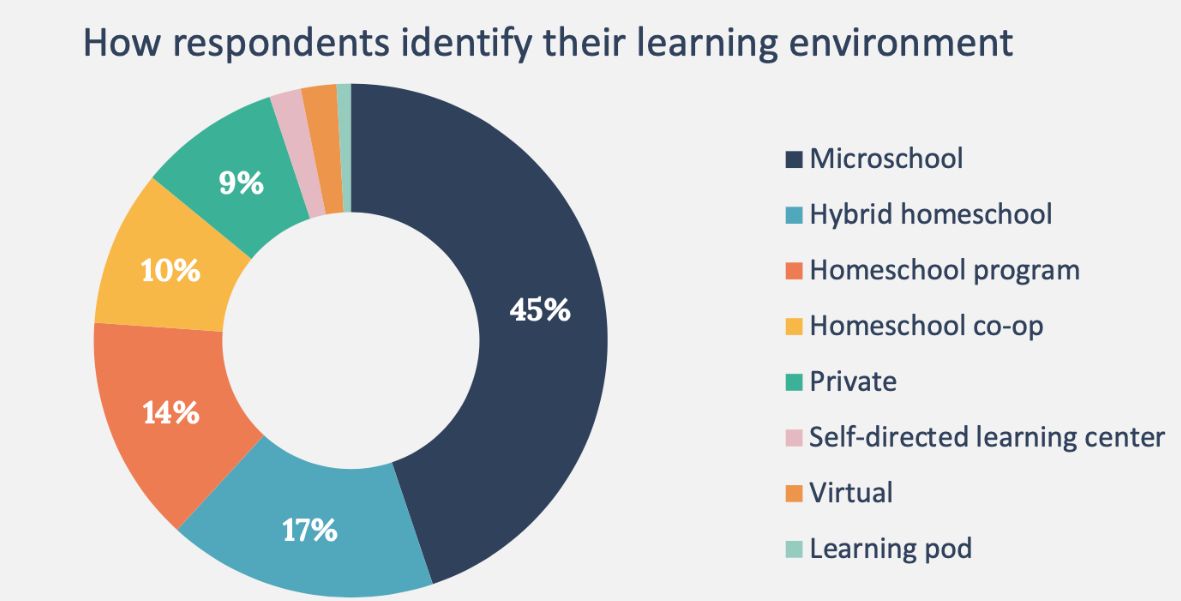

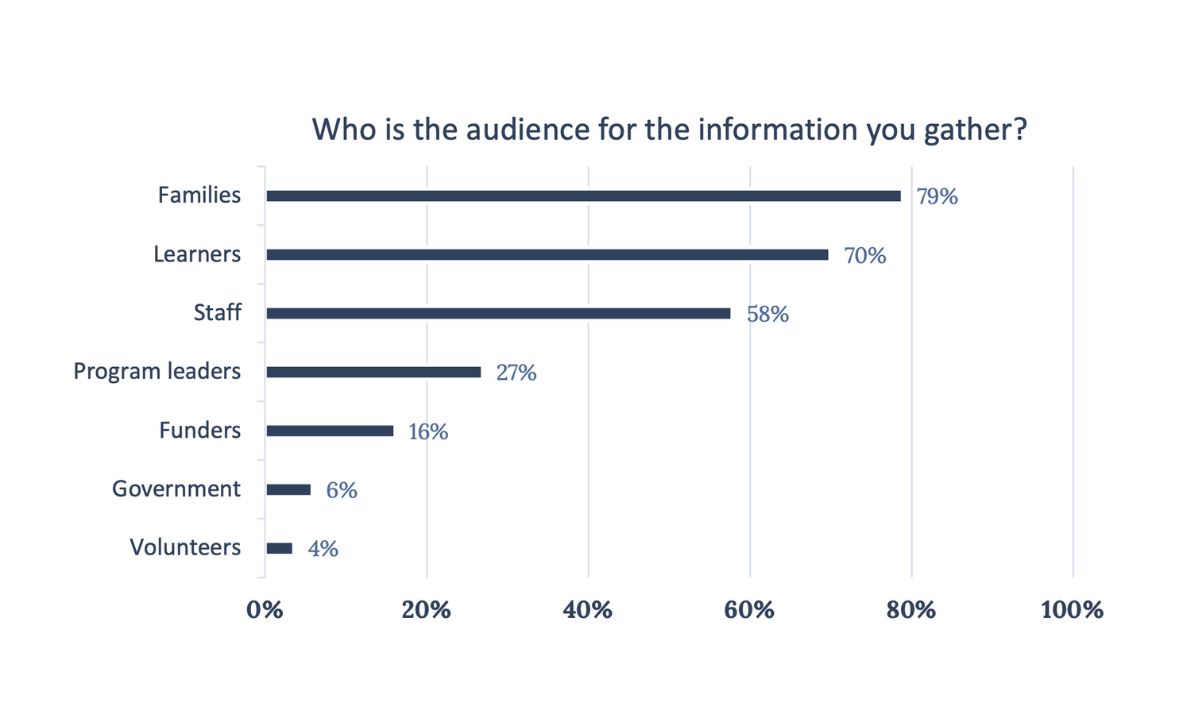

Her reliance on widely used assessments is not unique in the expanding universe of school choice options, according to a recent report from Vela, a nonprofit that promotes and provides grants to such programs. Most leaders of unconventional schools use methods like observation, student presentations and projects to track progress, but more than half also use standardized tests or assessments built into online curriculum — like DreamBox and Zearn. Leaders of such programs say parents are their number one audience for the data. But with more states allowing families to use public funds for tuition at microschools and other private school programs, there’s also increasing demand for greater transparency into how students stack up against their peers in district schools.

Burgess, previously a public and charter school educator, doesn’t have a problem with that.

“I think we’re at a very pivotal point in this whole movement,” said Burgess, who also has an online program that serves students from 19 states. “A lot of what we’re doing needs a light shined on it — not just for parents to say ‘Oh, it’s something different. Let me go try it’ — but more so the country can see this might be the new way of educating kids and providing families with choice.”

Vela, with a network of 3,000 founders of alternative schools, was “uniquely positioned” to survey leaders on how their schools define and measure student success, said Meredith Olson, president and CEO.

Of the 223 programs that responded, 70% said they track academic progress, but ranked developing students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills as more important than reading and literacy skills — 74% and 66%, respectively. Nearly 40% of the school programs said they measure math skills, and 13% said they don’t track anything.

Programs using digital tools are more likely to capture student assessment data using education technology from Khan Academy than any other program, Vela found in its survey. More than half of school founders said they use the popular website, with much smaller percentages using Lexia for reading (24%) or Zearn for math (15%).

Laurie Hensley, who runs the Learning Essentials microschool on an acre of property southeast of Phoenix, doesn’t let her students move to the next level until they score at least 90% in Lexia. Sometimes she “has a little chat” with parents if their child still can’t master a lesson after multiple attempts.

“But most of the time kids are progressing,” said Hensley, who worked as a paraprofessional in a charter school before launching her own program five years ago. “The whole point of being out of a public school is that they progress, even if it’s slower. As long as they’re moving forward, I don’t worry about them.”

Doug Harris, a Tulane University economist who studies school choice, including education savings accounts, said he’s not surprised that many microschool leaders rely on Khan Academy to tell them how students are performing.

“Microschools have only one or two teachers and they can’t be expert in, or create assessments for, such a wide variety of material,” he said. But even if public funds are paying for students to attend a microschool, the public won’t necessarily see that data. “Khan doesn’t provide useful info to anyone but those families and educators in the school.”

That’s not good enough for many opponents of ESAs, especially those in Arizona, which places no academic requirements on private programs that serve students with public funds. Criticism has spiked in recent months as the state makes budget cuts to accommodate growth in the program.

Holding microschools accountable

“Microschools propped up by taxpayer funds should be held to the same standards as public schools, which means they should take the same tests and post the same level of results,” said Beth Lewis, executive director of Save Our Schools Arizona, a public school advocacy organization that strongly opposes the state’s ESA program. “Otherwise, it’s not really about school choice at all, since parents don’t have access to any information about the microschool’s academics. And taxpayers have zero information about their return on investment.”

Jenn Kelly, who runs Education Through Adventure microschool in Scottsdale, agrees that ESA-funded programs should be held accountable for student achievement. But she thinks portfolios full of student work provide a more accurate picture than tests. The question, she said, is who would review the assignments.

The state education department’s ESA staff “is already overloaded with purchasing and vendor pay requests,” said Kelly, a former special education teacher in district, charter and Catholic schools. “What happens if a child does not show any growth … from year to year? Does the state pull the ESA funding for that child? Every answer raises more questions.”

Unlike Arizona, some states with ESAs or vouchers, like West Virginia and North Carolina, require programs to administer either state tests, or another standardized assessment, and submit the data to the state.

In West Virginia, Michael Parsons, who runs Vandalia Community School in Charleston, said he’s interested in how students in his school compare with those in other microschools, as well as those in public schools. But he’s most concerned about his students making progress.

“Most important as a teacher is accountability to my students and their growth, and as an administrator, accountability to my staff,” he said. “If I can keep those two things on par, then accountability to parents, taxpayers, regulators happens by default.”

At Burbrella, Burgess said she could have given the same end-of-grade assessments that students in North Carolina public schools take, allowing for a direct comparison, but she described them as “not kid-friendly” and decided against it.

One reason parents seek out unconventional models is because they feel public schools have a narrow focus on testing.

Bryant remembers how stressed her oldest daughter Ebony would get before state tests in New York City, where they lived before relocating to Burlington.

“She freezes up and does terribly. Compared to her performance in school, it was like night and day,” she said. At Burbrella, assessments don’t create the same level of anxiety. “It’s more like, ‘We’re going to assess where you are, and then we’re gonna work from there.’ ”

Disclosure: Walton Family Foundation, Stand Together Trust and the Beth and Ravenel Curry Foundation provide financial support to Vela and to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)